18 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

Several recollections and artifacts of Paul McCartney’s December 1968 trip to Portugal exist today, but one thing we lack is a clear timeline of his day-to-day activities. There’s no diary, no printed itinerary. We do know the kinds of things he did – spending time at the beach, visiting local towns, hiking in the mountains. It’s mostly based on Linda Eastman’s photographs or Hunter Davies’ written memoirs.

The most enduring document of the trip is a song. “Penina” wasn’t the first song with a “McCartney”-only songwriting credit – the 1967 The Family Way soundtrack holds that distinction – and it was never formally recorded by Paul or the Beatles. But “Penina” is one of the few tangible things sprouting from the trip, between several recorded versions by a variety of acts, a newspaper story about the Paul giving a song away as “a £20,000 holiday tip” and a resultant, ragged performance of the song during the Get Back sessions.

I’ve written up the origin story of “Penina” at some length before, but let’s quickly recap the basics: One late night during his Portuguese holiday, Paul showed up drunk (by his own account) at a hotel in Alvor, reportedly to exchange some currency. The house band, Jotta Herre, was performing at the hotel bar in the early hours, and Paul accepted an invite to hop on stage. Here’s Paul’s account of what happened next, as he told the other Beatles on January 9, 1969:

And I sat in on drums, and they said, ‘Give us a song.’ So I said, OK.

[Singing] I’ve been to Albufeira, had a great time there

It was called La Penina, the hotel. And they were all digging it and singing along, and it was good.

The January 9, 1969, Daily Express story, which first mentioned “Penina” to the public, quoted Beatles publicist Derek Taylor downplaying Paul’s gift of music, saying “this was not a whole song he gave to the bandleader. It was more a rif.”

But, as the paper continued:

Northern Songs shareholders in fact are presently benefiting from a rif, “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” John Lennon and Paul McCartney borrowed – from another performer, Jimmy Scott.

Paul was furious in reading that January 9 report, saying his offering of “Penina” as a throwaway was no different than his reception and reinterpretation of Scott’s phrase.

“You haven’t got a riff when you say ‘hello,’” Paul said to the other Beatles. “That’s the riff I got off of Jimmy Scott, those two words (“Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”). You’d think I’d taken his life. It’s not as though he wrote the song.”

We don’t know precisely when the “Penina” performance occurred. There isn’t any audio or photographic evidence. In 2021, the hotel offered a reward of a three-night’s stay to the best photo submitted of Paul performing there, but as far as I can tell, no one ever cashed in the reward. Maybe there’s a snapshot somewhere in Linda’s archives.

For the purposes of getting the “Penina” night on my December 1968 agenda, I’m placing it here, on December 15, perhaps selfishly for my own narrative purposes. I’m in no way proving or definitively saying that this is when it happened. But it’s as good a guess as any barring any proof to the contrary. This would have been the early hours as Saturday night becomes Sunday morning (not that days of the week matter much when you’re on holiday), and it’s certainly feasible.

Again, you can read a fuller account of the “Penina” origin story here.

Now let’s tie “Penina” back to “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” again, this time to help clear up some myths about the latter.

The song was sneaking up the singles chart in the UK, not by the Beatles, but releases from six artists clamoring for the top spot. Marmalade had the inside track – see yesterday’s entry for more on that.

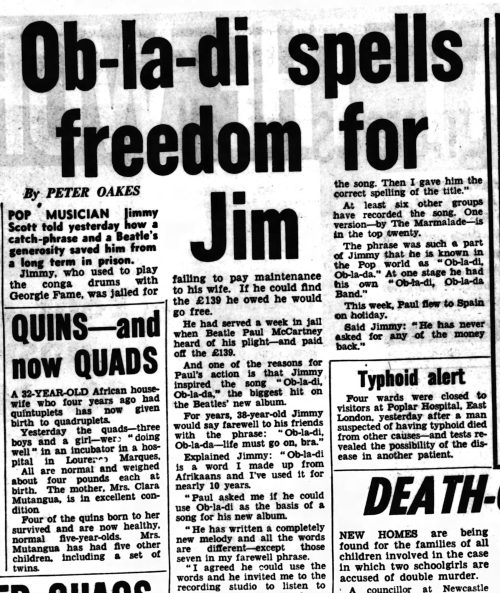

On this December 15, 1968, Jimmy Scott earned a small feature in the Sunday People newspaper. This obscure interview presents several insights that challenge today’s established wisdom about “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” But first, a little of what we’ve been led to believe. Stick with me, I’ll get back to this interview, and December 15, 1968, soon.

I’m going to point to the song’s Wikipedia page as we see it in mid-December 2024, because it’s the easiest target to pick on, the top Google search result and presumably the most viewed online resource on the song’s development. But it, the sources it cites and all the websites and publications that repeat this information are incorrect on a few relatively key facts. This isn’t the same as being off a day or two on something. From Wikipedia:

After the release of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” in November 1968, Scott tried to claim a writer’s credit for the use of his catchphrase.[15][6] McCartney said that the phrase was “just an expression”, whereas Scott argued that it was not a common expression and was used exclusively by the Scott-Emuakpor family.[12] …

Later in 1969, while in Brixton Prison awaiting trial for failing to pay maintenance to his ex-wife, Scott sent a request to the Beatles asking them to pay his legal bills. McCartney agreed to pay the amount on the condition that Scott abandon his attempt to receive a co-writer’s credit.[18]

Now let’s get into what Scott said in the December 15, 1968, Sunday People interview, as reprinted above, here with my emphasis:

POP MUSICIAN Jimmy Scott told yesterday how a catch-phrase and a Beatle’s generosity saved him from a long term in prison.

Jimmy, who used to play the conga drums with Georgie Fame, was jailed for failing to pay maintenance to his wife. If he could find the £139 he owed he would go free.

He had served a week in jail when Beatle Paul McCartney heard of his plight — and paid off the £139.

And one of the reasons for Paul’s action is that Jimmy inspired the song ” Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da,” the biggest hit on the Beatles’ new album.

For years, 38-year-old Jimmy would say farewell to his friends with the phrase: “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da – life must go on, bra.”

Explained Jimmy: “Ob-la-di is a word I made up from Afrikaans and I’ve used it for nearly 10 years. “Paul asked me if he could use Ob-la-di as the basis of a song for his new album. “He has written a completely new melody and all the words are different—except those seven in my farewell phrase.

“I agreed he could use the words and he invited me to the recording studio to listen to the song. Then I gave him the correct spelling of the title.”

…

Said Jimmy: “He has never asked for any of the money back.”

This contemporary account exposes a few key issues with the accepted knowledge surrounding Scott’s relationship to the song. While we know Scott complained about credit for “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” — Paul mentions it on several occasions in the January 1969 Nagra tapes — in December 1968 Scott himself admits the quid pro quo. Paul made the deal — charity, perhaps — before the song’s release and success.

(Jimmy Scott plays conga drums on an early take of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”)

Your mileage may vary on where you draw the line on cultural appropriation, but there’s a big difference between Paul using a phrase that was part of Scott’s Nigerian family heritage and a word Scott admitted he “made up” and used for only the last decade.

Paul gets a little bit into the agreement with Scott in 1997’s Many Years From Now (as later reprinted in the book packaged with the 2018 White Album deluxe reissue):

He was a great guy anyway and I said to him, “I really like that expression and I’m thinking of using it,” and I sent him a cheque in recognition of that fact later because even though I had written the whole song and he didn’t help me, it was his expression.

That memory seems in line with Scott’s interview published December 15, 1968.

***

It was front-page news the next day. Celebrity lawyer David Jacobs, 56, was found dead, hanging in his garage at 4:30 p.m. at his Sussex home on Sunday, December 15. News reports said he was recently in ill health and had suffered a nervous breakdown.

Jacobs was the lawyer for Beatles manager Brian Epstein, and while not necessarily a villain in their story, to a large degree he earned responsibility for the horrendous merchandise deal the Beatles were signed to at the height of Beatlemania.

At this point, the death was a mystery but police said they did not suspect foul play.

Sir Laurence Olivier, Judy Garland, Marlene Dietrich, Shirley Bassey, Donovan and Liberace counted among what the Daily Mirror said were his 5,000 clients. “He was the lawyer for almost every big pop group in the country,” according to the paper.

Jacobs was a celebrity lawyer, and a lawyer that was a celebrity. A piece in the December 16 Evening Standard elaborated:

David Jacobs was one of the very few non-political British lawyers to achieve fame in his own right. His services, for any pop star or actor in trouble, were de rigueur.

…

During a decade in which lawyers tentatively emerged from anonymity, David Jacobs stood out as a rare, exquisite (a colleague’s adjective) public advocate, one who was subject to the same prominence as his clients. He was therefore exposed to the same sour grapes, the same skepticism, as well as the same glamour.

Even with his role in costing the Beatles millions and millions of dollars, the Beatles maintained a friendly relationship with Jacobs. Ringo Starr honeymooned with Maureen at Jacobs’ house — the same one the lawyer was found dead in — in 1965.

On the news of Jacobs’ death, the Beatles issued a statement: “He was a great friend to all the Beatles and of course, to Brian. He was always there when he wanted him. He was a very steadfast man.”