This time, Paul McCartney’s line was delivered with a smile: “And then there was one.”

It was up to the viewers of the 2021 Get Back docuseries more than 50 years later to make out the invisible wink and deliberate nod to Paul’s tearful “and then there were two” from a day before — though in 21st century TV time, it was only 12 minutes earlier.

While there was just one Beatle at Twickenham Film Studios in the early going on January 14, 1969, Paul wasn’t alone for too long, not even 20 minutes on the Nagra reels capturing the sessions’ audio largely in real time.

Then there were two once again as a sleep-deprived Ringo Starr bounded in, and the Beatles’ rhythm section exchanged exaggerated greetings.

Ringo: “Morning, Paul!”

Paul: “Morning, Rich!”

Ringo: “How are you this morning?

Paul: “OK!”

After a full-arm stretch and crack of the knuckles, Paul – who had been sitting at the piano — struck the keys, and Ringo immediately joined in.

Maybe I’m not giving January 1969 Ringo enough credit as a piano player, but I’ll leave it as an open question if this was a pure improvisation or something specific Paul and Ringo had worked on before.

This is not to say Ringo was a finished product as a piano player. You can see him bracing one hand with another as he slapped out high notes — maybe it was just a gag — playing the high notes while Paul pounded out the chords.

Paul casually delivered a lyric to their song. A jumpy slice of New Orleans improvisational piano jazz, it lasted all of 70 seconds.

Well, I bought a piano the other day

I didn’t know music to play

You had to play the goddamn thing

Oh, baby!

(Or something close to that)

It’s an amusing callback to Ringo’s own “Picasso” from early in the sessions, from the “I bought a Picasso” line down to the closing “oh baby,” which was a signature Ringo closing lyric at this point. Paul and Ringo clearly had a great time playing together, something that was obvious to viewers in 1970 as much as it is to us today.

This little slice of life coexists in Let It Be and Get Back in nearly identical presentations. Let It Be’s version lasts all of 5 seconds longer – both are slightly edited down from the original performance. The differences between the two visuals are purely cosmetic and seem like change for change’s sake, showing the duo’s hands at the piano when the other shows a view from their left, for instance.

But then there were two (more important differences).

The first is the timeline. In Let It Be, the sequence is preceded by a January 9 version of “One After 909,” appearing about 13 ½ minutes into the film. After the piano jam, Let It Be sends the viewer into a January 6 rehearsal of “Two of Us” that eventually leads to the “I’ll play if you want me to play” argument (Director Michael Lindsay-Hogg uses Paul’s running his hands through his hair at the end of the performance to lead directly to the next scene of ensuing frustration.)

The transition as it appears in Let It Be.

Get Back roughly follows the progression in real time on the morning of January 14. It doesn’t come immediately after clapper loader Paul Bond said he wanted himself to buy a piano as it does in Get Back, but you can certainly see why that narrative device was used, and it was close enough in real time to work.

There’s another very notable divergence between the two films. When it came to the credits in 2021, then there were three (songwriters). Based on that clear first lyric and presumption it was a newly published original, the song was credited on screen as “I Bought a Piano The Other Day,” a Lennon/McCartney/Starkey composition.

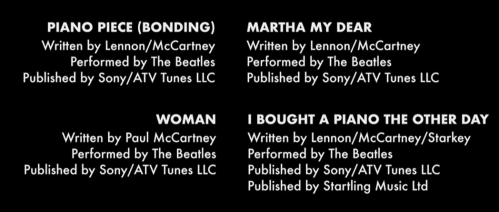

Even with John clearly not yet on site, the Lennon/McCartney credit structure was used (as it was elsewhere with similar absent credits – but not future solo songs), with Rich Starkey an obvious contributor. (Just look at “Piano Piece [Bonding].” That shouldn’t be a Lennon/McCartney song, since it’s probably already a Jesse Fuller original. More on that in the previous post.)

To paraphrase an earlier lyric credited to the Lennon/McCartney/Starkey songwriting trio, they didn’t even think of it as something with a name — or something long-forgotten that already had a name for the last 50 years. After all, it already had a title, and it wasn’t “I Bought a Piano The Other Day.”

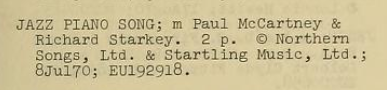

Nobody has never spun an official version of “Jazz Piano Song” on a turntable or streamed it on Spotify. But that recording, originally released as part of the Let It Be film but not on the soundtrack LP, is the real thing. “Jazz Piano Song” – admittedly not the most dynamic title — was copyrighted in the U.S. on July 8, 1970, by Northern Songs and Startling Music, credited to McCartney/Starkey. It’s a matter of semantics if it was really released, but it certainly came out.

From the July-December 1970 volume of the Library of Congress’ Catalog of Copyright Entries of Music.

Today in 2024, then, there are two (copyrighted versions of the same song): “Jazz Piano Song” and “I Bought A Piano” are one in the same. I can only guess the decision to separately copyright the latter was an oversight, a generic disregard and abandonment of “Jazz Piano Song,” Let It Be and its era. Kudos to the Lennon Estate for sneaking away a few extra dollars and pounds for a song he had absolutely nothing to do with and was already accounted for, credit-wise.

It took more than 25 years for the McCartney/Starkey duo to team up on a follow-up composition. The liner notes to Paul’s 1997 LP Flaming Pie might obliquely reference “Jazz Piano Song,” saying in the description of “Really Love You” that it was “[c]redited to McCartney/Starkey – a first-ever credit for a released tune.” That note could also be referring to “Angel in Disguise,” an early ‘90s Paul demo with an added verse by Ringo, and thus another McCartney/Starkey unreleased track. Or it could just be covering behinds on the assumption there must have been other unrecorded and unreleased McCartney/Starkey tracks from 1962-1997.

From the 1997 liner notes to Flaming Pie.

It’s at this point on January 14, 1969, the focus shifted from an obscure McCartney/Starkey song credited twice into a modest hit song written by Paul McCartney alone that wasn’t credited to him at all. (Some of this sequence appeared in Get Back, albeit compressed and a little out of order, too, although not in any way that misrepresented the moment.)

“Did you write ‘Woman’ by Peter and Gordon?” Michael asked. “I loved that song.”

Paul said he did too.

“Woman” was a 1966 single for the since broken-up duo. It was also a deliberate experiment conducted by Paul.

“Bernard Webb, an English law student in Paris, sent this song to the Beatles, who having plenty of their own, passed it on to their old mates,” wrote one representative review of the song, outlining the origin story fed to the press.

Like Paul Ramon before, and Apollo C. Vermouth and Percy Thrillington to come, Bernard Webb was one James Paul McCartney, this time taking a pseudonym – “a very inconspicuous name,” per Paul in the May 1966 Beatles Book magazine — in a ploy to see how well his song would chart as an anonymous author and not half of the world’s most famous pop songwriting team. The answer was modestly well, with the big production number landing in the top 30 in the U.K. and inside the top 15 in the U.S., although some of the movement up the charts did come after the secret was let out that Paul was behind the curtain.

The “mammoth Peter and Gordon treatment,” as Paul described it, gnawed at the songwriter years later. (Meanwhile, as we learn by watching Get Back, Ringo spent part of this performance mugging for the cameras.)

“We did a much better one very first time we ever did it,” Paul said on January 14, after singing the first verse a capella. “It was very dry. Just little. With like about eight violins. … We were very fussy at the time, didn’t like it, so it got turned into a mammoth ballad.”

Modestly, he concluded, “It’s a great song” before delivering a straightforward performance at the piano, repeating the first verse several times. He later played it again imitating the “great big Gordon bit” to laughter.

I wonder if Peter’s still got the original thing of that, cause we did a great version first time we did it. Only Gordon couldn’t get the high notes. … But it was all right though, it was OK. It’s just we were so fussy we thought “this is the song, this is the one.” And they’re so fussy about it, that we chucked it, jacked it in and just let them go and do it again. But they did it the next time as mammoth Peter and Gordon treatment. It’s too sort of big. The first time we did, it was little, it was great.

An acetate of the “original thing” – purportedly featuring Paul on drums — went to auction in 2013, and quickly founds its way online.

A mammoth treatment isn’t necessarily a disqualifier for Paul, though, who resumed playing the piano after a brief conversation celebrating Johnny Cash (look for that in a future post!). In Get Back, Paul introduces the song saying, “I had one this morning.” In fact, he said that earlier, when playing “The Day I Went Back to School.” On the Nagras, Paul gave no indication the song was an original or anything beyond something he was improvising.

Paul scatted a few indecipherable lines, although a few are identifiable, sung in an exaggerated fashion: “We’re just busy riding, driving in the back seat of my car.”

Two years before it concluded RAM (and eight years before Thrillington’s “cover”), “The Back Seat of My Car” was new enough Glyn asked if Paul was playing a Beach Boys song.

“It’s just like a skit on them,” Paul replied.

Indeed it played out like a comedy– thankfully, this sequence made Get Back, too – as Paul openly played to his audience, embellishing high and low harmonies and vocalizing brass and percussion as he shared draft lyrics of teenage romance. “Gee, it’s getting late!” drew big laughs, for instance. Mexico City hadn’t been introduced as a destination, and the subjects didn’t yet believe that they can’t be wrong.

Conceived in summer 1968, “The Back Seat of My Car” — which was ultimately credited to Paul alone — wasn’t finished in January 1969, but Paul clearly had scoped out the grand scale of the song, more than two years before he’d ultimately employ an orchestra to perform George Martin’s score for the song.

Having completed his enjoyable reveal of “The Back Seat of My Car,” Paul left the stage to take a call, and the Nagra microphones shifted to a conversation between Ringo and Michael, following a brief appearance by Mal Evans. The roadie himself had just taken a call from John, who for a consecutive day was late to the session.

“What did Mal say? … What’s going to happen this morning?” Michael asked Ringo.

“Nothing,” he replied. But …

“This afternoon, watch out!”

The canteen discussion stands at the core of the day’s drama, but Beatles still made music and did their best to sort out their issues best they could. Dig in here for a better understanding how the day played out:

The canteen discussion stands at the core of the day’s drama, but Beatles still made music and did their best to sort out their issues best they could. Dig in here for a better understanding how the day played out: