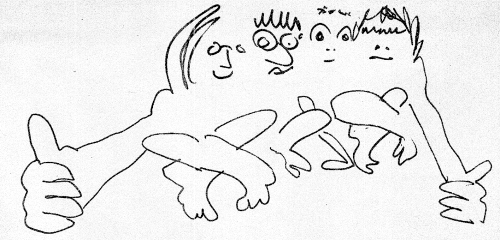

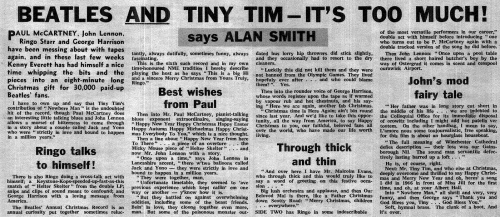

The Beatles, as depicted by John Lennon in November 1968, as published in the December 7, 1968, issue of New Music Express.

The Beatles, as depicted by John Lennon in November 1968, as published in the December 7, 1968, issue of New Music Express.In my faith, we count down the 25 days to the start of the Get Back/Let It Be sessions. This is completely normal.

To operate this particular digital advent calendar, simply click the current day below and read up on what our boys and their extended circle were doing in these days leading up to their Most Holy Assemblage at Twickenham Film Studios on January 2, 1969.

(You can also click on any previously published days)

24 days until the start of the Get Back sessions: Setting the scene

This was a really good time to be a Beatles fan.

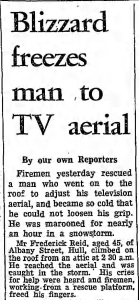

Pick up any of the big music papers, and you could read about the tantalizing prospect of the band’s imminent stage return. It may not be at London’s Roadhouse as first rumored, but it’ll be somewhere.

And they’ll play all-new music! No, they didn’t need to start writing stuff from scratch. They just put out brand-new double album, after all. Their eponymous LP landed at the top of the charts just a few days earlier in its first full week on the shelves. The White Album was still new enough that reviews continued to dot newspapers around the world.

Of course, they featured on the singles charts, too – “Hey Jude” was still Top 10 in the US, and hanging around the Top 30 in the UK even after 14 weeks. The Paul McCartney-produced “I’m the Urban Spaceman” by the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band sat at its peak of No. 13 on the UK charts, while Mary Hopkin’s Apple Records smash “Those Were the Days” – also produced by Paul – stuck in the US and UK charts, even after its peak (Paul had within days just wrapped sessions producing Hopkin’s debut LP).

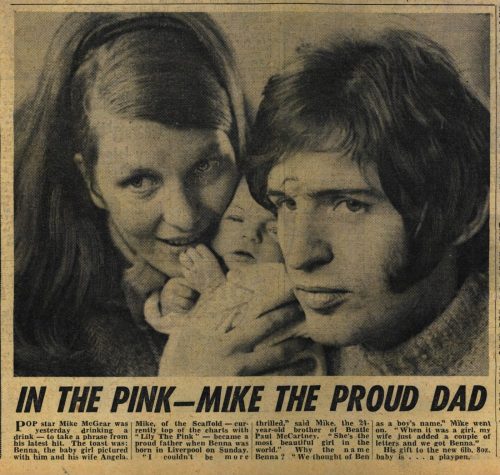

On the UK charts, the only thing hotter than McCartney was … McCartney. Paul’s brother Mike, performing as Mike McGear with the Scaffold, had the No. 2 song in the country with “Lily the Pink.” It would be on its way to the top of the pops.

It wasn’t just on vinyl — the Beatles dominated as true kings of all media. Yellow Submarine, out since the summer in the UK but in US theaters for only a few weeks, had established its reputation as a clear-cut critical and commercial smash. Even in the world of print, the Beatles were easily accessible with Hunter Davies’ authorized biography flying off shelves since its release in October.

The book was outdated when it came to the Beatles’ personal lives. A 26-year-old bachelor, Paul had already seen his engagement to Jane Asher fizzle, and gossip about his girlfriend Linda Eastman was mainstream at this point. Syndicated articles sourced from a recent story in the Daily Mirror teased the “romance” but Paul remained evasive.

“I can’t say what will happen,” said Paul. “It may happen, it may not. Let’s say Linda is with me now and I’m very happy about it.”

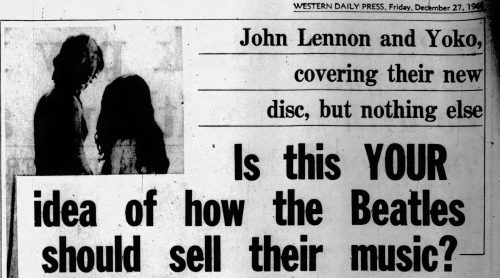

John Lennon, who was officially divorced for about a month, wasn’t so coy. Naked on record racks since November 1968 — more in theory than in practice, since the record wasn’t easy to purchase — John and girlfriend Yoko Ono were as public a thing as possible. For all the commentary and protest of the Two Virgins cover, one that was published in American papers this week was perhaps a low blow, when a former disciple of the Maharishi objected to John’s depiction because “he’s got a horrible-looking body.” His body of work was set to expand — he’d rehearse for an imminent performance on the Rock and Roll Circus the following day.

George Harrison was finally back in England after a dynamic few months in the US. He produced Jackie Lomax’s debut LP for Apple and hobnobbed with Frank Sinatra in LA and enjoyed Thanksgiving with Bob Dylan and the Band in New York before winging it home (media reports said he returned by sea, but in the January 1969 Beatles Book Magazine, Mal Evans clarified they flew back to England).

Budding actor Ringo Starr had Candy in the can, ready for imminent release, and was studying the script for his next role – The Magic Christian, due to begin shooting at Twickenham Film Studios in February 1969.

Meanwhile in New York – where both George and Paul separately spent leisure time in previous weeks – Billy Preston was hard at work, in the midst of performing with Ray Charles during his two-week residency at the Copacabana.

The British music scene was facing serious fractures in early December 1968, with the likes of Cream, Traffic, the Hollies, the Animals and Jethro Tull all breaking up or facing prominent departures in just the last few days and weeks.

It only went to further contrast the rest of the world from the mighty Beatles, who were due to reassemble and continued to push to greater heights even while standing at what could be seen as their peak.

23 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

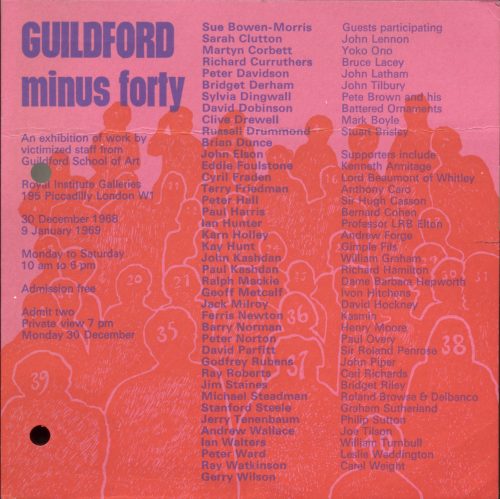

While a Beatles group performance remained aspirational, John Lennon’s Dirty Mac prepared to do the real thing after spending this Tuesday rehearsing. Formed explicitly for the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus on just a few days’ notice, John fronted this two-day supergroup that included Eric Clapton (guitar), Keith Richards (bass) and Mitch Mitchell (drums). Yoko Ono would perform with the Dirty Mac, but would be credited separately. The January 1969 issue of the Beatles Book Monthly assured us George was hoping to join the group but couldn’t because of “urgent remixing sessions” for the Jackie Lomax LP.

Having been some days in preparation: The cast of the Rock and Roll Circus pose for promotional photos on Dec. 10, 1968

The Rock and Roll Circus deserves a deep study of its own for how it relates to the Beatles – this post isn’t it – but it’s important to mark the personnel present. Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who had an established working relationship with both the Beatles and the Stones, directed the program and tapped Tony Richmond as cinematographer. Glyn Johns, another Stones veteran, engineered the Circus’ sound, while photographer Ethan Russell – himself an increasing part of the Stones’ circle – documented the show. These figures would be at the core of the small group chronicling the Beatles starting just a few weeks later.

Michael related how the band was formed in a 2019 story in NME:

So Mick called John and he said, ‘Yeah, I’ve been playing with Eric Clapton just for fun, he could play, who could play bass?’ And Mick said, ‘Maybe Keith could play bass’. We all liked Mitch Mitchell from the Hendrix Experience so in that one phone call we had John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Keith Richard and Mitch Mitchell to fill that supergroup spot. So that’s not too shabby. That’s the way it was at the time. It was partly to do with the friendship and the mutual admiration that the key players had for each other that made the show possible in the first place.”

Intertel’s Wycombe Road studios at Stonebridge Park in Wembley served as the venue. Michael said during Get Back sessions that he tried to book the Houses of Parliament for the Circus, but “they didn’t go for it.”

Among the songs rehearsed by the Dirty Mac – named as a play on Fleetwood Mac, per John – were the Beatles’ “Revolution” and a warmup jam, neither of which were recorded for the show itself. The songs would eventually surface on a 2019 reissue of the Rock and Roll Circus.

A report from the Dec. 21 Melody Maker conceded rehearsals progressed … slowly.

During the first day rehearsal which began at midday there were seventeen items to run through. By five o’clock only three of four acts had been dealt with.

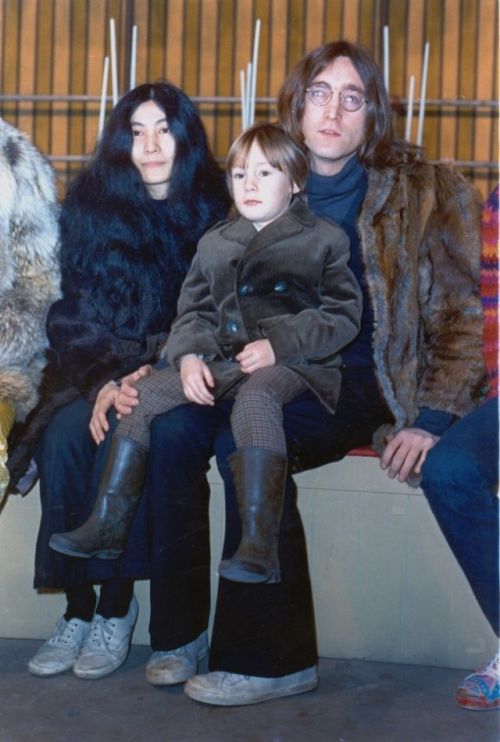

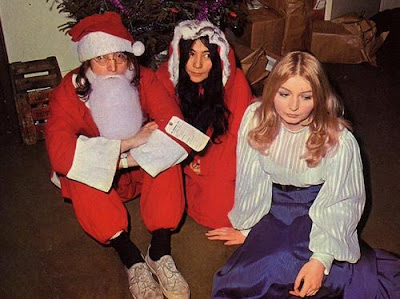

John’s son, Julian, was on hand, and the day included a promotional photo shoot for the event. It also included a variety of auditioning circus acts. Michael wrote in his 2012 memoir, Luck and Circumstance, that Yoko told him if he chose to employ the boxing kangaroos on site in the Circus, John wouldn’t perform the next day.

“I’m not sure if she’d talked to John about this,” Michael wrote. “But needless to say, the kangaroos hopped back into their holding pen and were not seen again.”

According to a 2019 interview with Michael in Beatlefan, John wasn’t the first choice to front a supergroup on the show (it was Steve Winwood). He wasn’t even the first Beatle considered.

We first thought, would Paul McCartney want to form a group for this show? Paul would leap into anything if he thought it was right, but given all the other stuff that was going on, we didn’t think that Paul would want to appear without The Beatles. Mick and I didn’t think it was gonna happen. Then, we thought John might have the temperament to jump into the water without his flip-flops on.

Turns out Paul was the one packing his flip-flops on Dec. 10.

Come for the sandy beaches; stay because they’re an old Napoleonic War ally. A travel story on the Algarve, from the Dec. 12, 1968, issue of the Birmingham Evening Mail.

The Algarve was already trendy. Indeed, Paul experienced Portugal’s expanding resort region a few years earlier in early summer 1965, vacationing in Albufiera with then-girlfriend Jane Asher. He thrived there too: It’s where he started writing the lyrics to “Yesterday,” while batting away wedding rumors.

In 1968, Beatles biographer Hunter Davies informally invited everyone in the band to his Praia da Luz rental home, a former sardine factory. He wasn’t expecting Paul to spontaneously take him up on the offer this Tuesday night.

Many Years From Now, Paul’s 1997 authorized biography by friend Barry Miles, lays out the story: With Neil Aspinall’s help, Paul chartered a night flight and was joined by girlfriend Linda Eastman and her daughter, Heather. After landing at Faro Airport and cabbing it 50 miles, Paul woke up Davies with “shouts and pebbles on his window,” before he stuck his host with the taxi bill (Paul didn’t have any local currency).

“I thought at first it might be some drunken fishermen, on their way home,” Davies wrote in his own 2006 memoir “The Beatles, Football and Me.” Then I realised someone was shouting out my name – in a Liverpool accent. ‘Wake up Hunter Davies, you lazy bugger.’”

The account in Many Years From Now establishes that Dec. 11, 1968, is the date Paul departed to and arrived in Portugal.

I think that date is wrong, and instead, Paul and Co. arrived a day earlier on Dec. 10.

The reason is simple: A local, contemporary account said so, and it said so while he was in Portugal, not almost 30 years later in a memoir.

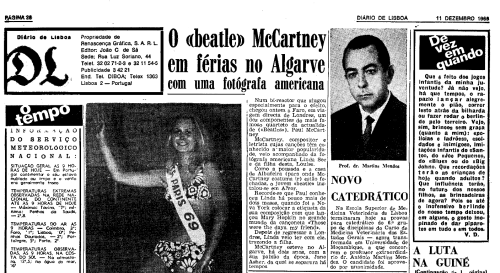

As published in the daily newspaper Diário de Lisboa on Dec. 11, 1968 (the 3rd, 4th and 5th editions), and translated by Google in 2023 (the emphasis in the first paragraph is mine):

The Beatle McCartney on vacation in the Algarve with an American photographer

In a bi-reactor that he rented especially for this purpose, one of the members of the most famous quartet today (<<Beatles>>) arrived in Faro yesterday, on a direct trip from London, Paul McCartney.

McCartney, composer and lyricist whose songs have enjoyed the greatest popularity, was accompanied by American photographer Linda See and her daughter, Louise.

As the inn and the house in Albufeira (where McCartney usually goes) are closed, the young <<Beatle>> settled in Alvor.

Remember that Paul met Linda just over two months ago, when he went to New York to label his composition with which he launched Mary Hopkin into the great world of the song <<Those were the days, my friend.>>

After returning to London, Linda came to see him, bringing his daughter.

McCartney was in the Algarve two years ago with his love at the time, Jane Asher, from whom he had separated some time ago.

To clarify some things: A bi-reactor is an airplane. The article used Heather’s middle name as her first, and late in the story said it was his daughter. They also used Linda’s married name “See,” which she stopped using in 1965.

BUT. I feel a newspaper wouldn’t get the day wrong, when it was happening within the last 24 hours. Saying Paul came “yesterday” is a lot more easily verifiable on a deadline than a foreign celebrity’s girlfriend’s last name or daughter’s first name. Think of the timeline involved, too: If Paul arrived late on the 10th, it would make sense news wouldn’t get out until early on the 11th, and indeed the news wasn’t in the first two earlier editions of Diário de Lisboa, but was in the final three.

With the timeline corrected, we’ll catch up more on the McCartney-Eastman vacation in the coming days as they settle in.

Just as Paul eyed a quiet escape on the Continent, he won a popularity contest back home. In a Daily Express poll of 5,000 readers unveiled on Dec. 10, Paul, the “driving force behind the Beatles” who “looks like a naughty choirboy,” more than doubled up the votes of runner-up Ringo Starr. George, liked for – among other reasons – his “hairy legs,” and John brought up the rear.

Rough as it was for George, at least wife Pattie Boyd could recoup some family pride, capping off this Tuesday as one of Britain’s “best-hatted women.” Specifically, Pattie earned milliner Edward Mann’s honor “for pioneering the floppy, one of this year’s best-selling styles.” Mary Hopkin was likewise recognized, for a boater hat.

Rough as it was for George, at least wife Pattie Boyd could recoup some family pride, capping off this Tuesday as one of Britain’s “best-hatted women.” Specifically, Pattie earned milliner Edward Mann’s honor “for pioneering the floppy, one of this year’s best-selling styles.” Mary Hopkin was likewise recognized, for a boater hat.

22 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

“The Rolling Stones needed a family show, and Mick [Jagger] wanted a family show. Mick said he wanted Ed Sullivan without Ed Sullivan.”

That’s how director Michael Lindsay-Hogg described the Rock and Roll Circus to Paul McCartney a few weeks later, in the midst of the Beatles’ Get Back sessions.

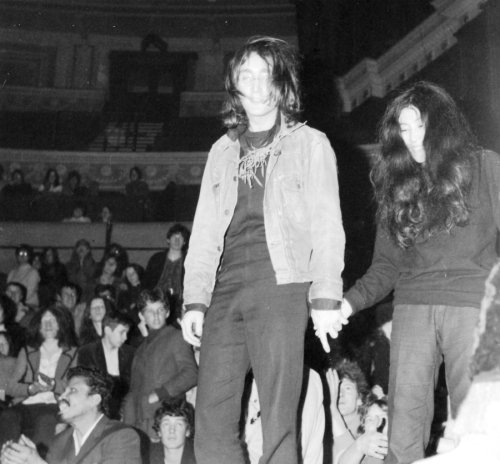

Fronted by John Lennon – introduced as Winston Leg-Thigh – the Dirty Mac’s evening show at Intertel’s studios in Wembley marked his first performance away from the Beatles since their formation. This circus act had a safety net, with John backed by Eric Clapton (guitar), Keith Richards (bass) and Mitch Mitchell (drums), as seasoned as ad-hoc band you could build.

Their fiery performance of “Yer Blues,” a fresh Beatles cut from the new White Album, speaks for itself and lent itself perfectly to the band. They sound absolutely terrific.

Yoko spent “Yer Blues” on stage in a black bag. She emerged as the band, joined by renowned Israeli violinist Ivry Gitlis, performed a song initially called “Her Blues” that was ultimately released as “Whole Lotta Yoko.” Let’s call it a basic rock-blues improv jam with a dueling lead provided by violin and Yoko’s imitable vocals.

The director didn’t expect Yoko’s performance. Here’s how he recalled it in 2019 for NME:

All I’d noticed vaguely was at the beginning of ‘Yer Blues’, someone was getting into a black bag at the edge of the stage, but I didn’t really take much notice of that because I was trying to figure out the best way to shoot the song. Then Yoko comes near the mike and you see John and Yoko looking at each other and John going ‘go ahead, go ahead’. Then Yoko starts to sing. I’d never heard her sing before and of course it’s very riveting and it didn’t stop. … She had been a quite well-regarded abstract artist in New York in the ‘50s, so she had a reputation in the avant garde art world. She wasn’t just a girl who turned up, she came with a reputation, although not many people in England knew who she’d been in New York.

The Dirty Mac wrapped their set early enough in the proceedings to allow John and Yoko to venture to BBC’s Broadcasting House and appear live during the first hour of John Peel’s “Night Shift” program, which ran from 12:05-2 a.m. Really, this should be the first item for December 12, but we’ll keep this at December 11, since John shared his immediate reaction to the Circus.

“It’s very exhilarating,” John told Peel. “The Who were who-ing, the Stones were stoning, the clowns were clowning.

Asked what other projects he was working on, John clarified, “[The Circus] wasn’t a project. That was Mick saying, ‘Do us a favor, Stevie Winwood’s pulled out.’”

Elsewhere in the same interview, John read “Jock and Yono” as well as “Once Upon a Pool Table,” two poems that would imminently appear on the Beatles’ 1968 fan club Christmas record. He introduced the poems as “a piece of paper called ‘Charles.’”

John and Yoko also promoted their December 18 Alchemical Wedding event scheduled for the Royal Albert Hall (“go naked” was Yoko’s suggestion) and, relatedly, discussed Two Virgins.

“I can’t see it being a pop hit,” John said. Still, he was chuffed it sold 700 copies the previous day in some “hidden underground-type open-air shops.” Referring to the couple’s growing inventory of recorded material, John said “when we’re old and gray, we’ll put out all the backlog we got.”

Listeners were treated to a brief live song: John briefly crooned — and whistled — “It’s Now or Never” to fill time.

After the interview, John and Yoko made the 10-mile return trek back to the Circus, which continued to around 5 a.m., when the Stones finally finished recording their set.

Ostensibly staged to promote Beggars Banquet, released just days earlier on December 6, the Rolling Stones mothballed Rock and Roll Circus, which wouldn’t see a formal release until 1996. Conventional wisdom holds the show was shelved because the Stones were upstaged by the Who.

Members of the Beatles were likely among the very first people to have seen initial edits of the show, while the band was working with the same director in subsequent weeks during the Get Back sessions. Indeed, the Rock and Roll Circus often served as a tangible point of comparison as the Beatles searched for their own live show concept in January 1969.

Paul McCartney very badly wanted to enjoy the Who’s terrific performance of “A Quick One, While He’s Away,” but blamed Michael for poorly capturing his subjects.

Paul, from the January 13 Nagra tapes:

It didn’t look right. I know it was a bad print. But like, I didn’t ever get into any one of the Who. Ever. It was the event all the time. And no one digs that. That’s over, that sort of event, I think. It really is now, if you’re trying to show him, I just really say just stick [the camera] on him.

…

Pete Townshend, I never saw him. I’d really like to look at him for a long time cause he fascinates me. … I’d like to really just see what he looks like after he’s done that thing (presumably his windmill guitar move).

You know, [I’d like to see] Keith Moon just sort of jabbering away on the drums, just for a whole number almost.

Naturally, John’s reflection on the evening was experiential, not observational, and it stuck with him to the end of his life, a dozen years later. John opened up to the BBC in his penultimate interview, on December 6, 1980, sharing these thoughts, in the context of the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival as well as the Rock and Roll Circus:

It was instantly creative, and there was no big palaver, it wasn’t like this set format show that I’ve been doing with the Beatles, where you go on and do these same numbers, “I Want to Hold Your Head,” you know (laughing). And the show lasts 20 minutes and nobody’s listening, they’re just screaming, and the amps are as big as a peanut. And it was more of a spectacular rather than rock and roll.

The first time I performed without the Beatles for years was the Rock and Roll Circus, and it was great to be on stage with Eric and Keith Richard and on a different noise coming out behind me even though I was still singing and playing the same style. It was just great experience. I thought, wow, it’s fun with other people you know?

And speaking of other people, let’s introduce one more key character at this circus – call him a firebreather, a strongman or a clown, maybe all three. Allen Klein was a footnote to John on December 11, 1968, but emerged as one of the most critical figures in Beatles history.

From Fred Goodman’s 2015 biography on Klein:

He came to the all-night recording session for only one reason: to meet John Lennon. He achieved his goal, but just. The set was hot and cramped, no place for a conversation let alone a full-blown seduction. Allen had to settle for a handshake and hope that he’d finally registered with Lennon as more than just another outstretched palm.

“I didn’t know what to make of him,” John recalled in the 1970 Lennon Remembers interview. “We just shook hands.”

At the precise moment John acted as the ultimate multimedia showman, appearing on stage before an audience and TV cameras before shuttling over to a live radio appearance, Paul sought to escape the spotlight and work on some things in private.

The last time he went to Portugal, in 1965 with then-girlfriend Jane Asher, the headline in the Daily Mirror screamed “A marriage hint by Beatle Paul.” But it was merely a hint, Paul conceding, “When, we don’t know. We prefer to get older and know each other better.” The couple was engaged, but never married, and Paul eventually began dating Linda Eastman.

Paul tied the knot with Linda Eastman in March 1969, but before that he popped the question in Portugal in December 1968. He felt – on the heels of extended time together that fall in New York and Scotland – they did know each other better.

Here’s Paul, as quoted in 1997’s Many Years From Now:

As our relationship solidified and we really started to feel very confident with each other, it was a question of ‘Well, shall I get off the pill then?’ And we talked about that, and I said, ‘Yeah!’ I don’t know why. It wasn’t like planning a family, it was more ‘If you like. We could see what happened. If anything happened. That would be all right.’ Then Mary was on the way, it was definitely not planned. And we decided, round about that point, to get married.

This trip to Portugal with Linda and her daughter, Heather– December 11 was their first full day there — was precisely that point.

21 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

A thousand miles separated Paul McCartney and John Lennon on December 12, 1968, yet the Beatles remained entwined in spirit, meeting the press and teasing a glimpse at the project they shared on the horizon.

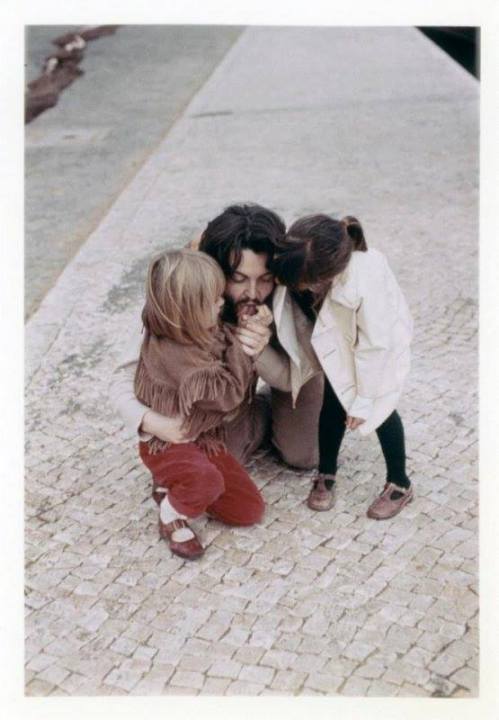

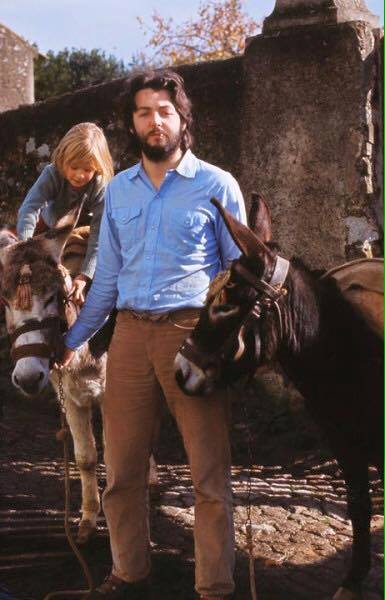

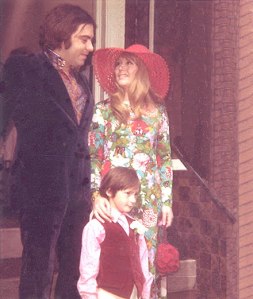

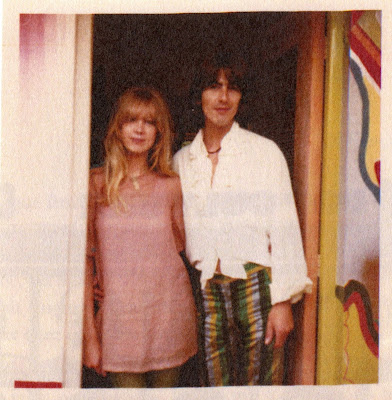

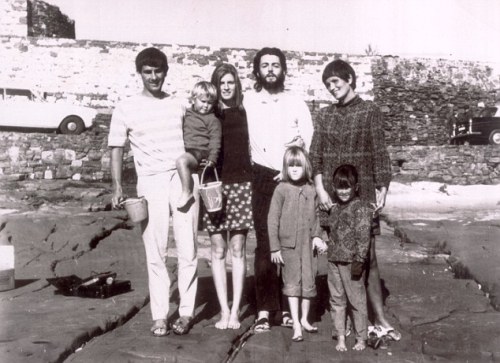

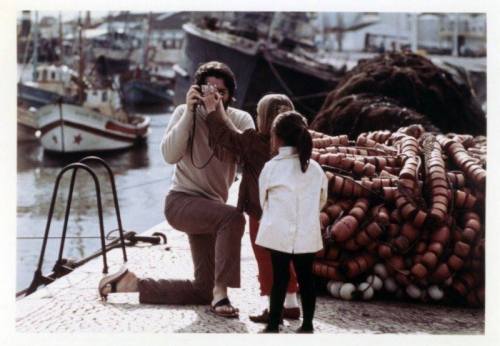

On holiday: Hunter Davies, Linda Eastman, Paul McCartney and Margaret Forster with children Jake Davies, Heather Eastman and Caitlin Davies.

Paul, girlfriend Linda Eastman and her daughter, Heather, vacationed for several days in Portugal in mid-December 1968 – contemporary reports put it at eight days, while host Hunter Davies maintained it lasted two weeks in later accounts. The January 1969 Beatles Book magazine said it was just a week, and that’s what I’m leaning toward myself for reasons that I’ll make clear when we get there.

It didn’t take long for locals to catch wind that a Beatle was there on holiday — even with his late-night arrival on December 10 and access to private lodging. As Davies related in his 2006 book “The Beatles, Football and Me,” upon landing at the airport, Paul asked someone “official looking” to exchange £50 to Portuguese escudo, but Macca grabbed a cab before getting the currency back.

“A story had gone round about this idiot Englishman giving money away,” Davies wrote. “Then one person had said, ‘Oh no, I recognized him, he’s not an idiot, he’s a Beatle.’”

And so the Beatle was out of the bag. It was around that point, on his third day in Portugal, Paul called on the media to make a deal. Per Davies, the Beatle offered to meet reporters one time in exchange for privacy for the rest of his vacation. Common wisdom holds this small, informal press conference happened on December 12, because it’s mentioned in newspapers dated the following day, and because Davies later wrote it happened on Paul’s third day in Portugal. But like many other events in this period, we’re going with educated guesses.

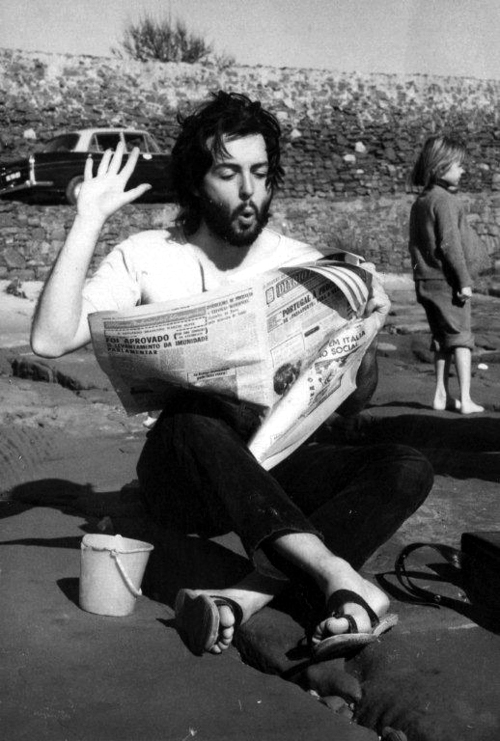

Paul held court on the private beach attached to Davies’ home. Photographic and film evidence of the meeting survived. What doesn’t seem to be circulating is a decent scan of any news coverage that emerged from the interviews. If one surfaces before I make it to a library in Portugal, please let me know!

The best we seem to have is the above scan from page 11 of the December 13 issue of Portuguese daily Diário Popular. If you’re one of the proud few who have studied Paul’s ’68 vacation to Portugal to any degree, you’ve probably seen this page. It’s clear enough to make out headlines and images, but most of the text is too fuzzy to get any decent read on what’s being discussed.

What we can make out (via Google Translate):

- The photo’s caption is simply “Paul McCartney & Louise [sic] Eastman, photographed on Luz Beach.”

- The box under the photo says: Paul McCartney speaks to << Diário Popular>> about his eventual marriage to photographer Linda Eastman.

- The main headline reads: “Anything could happen …”

- A subhed in the middle of the story says: “A new Beatles show on English TV.” Presumably this is Get Back-to-be.

- There’s a reference to “was a fool on English TV.” Maybe it’s something about Magical Mystery Tour? Just a guess.

- Hunter Davies and wife Margaret Forster earn a mention, and she’s named in reference to her popular novel, Georgy Girl.

Paul also wrote a greeting to the newspaper’s readers in English. Let’s note he represents his full group, not himself or even his family-to-be, inking “Love from the Beatles,” with a heart and arrow through it and his signature. On the other side of the page was a photo that looks like Paul sketching this very message. Again, Linda is named “Louise” in the caption. (When I worked at a newspaper, they would have skewered me if I got that sort of thing wrong so many times in one place.)

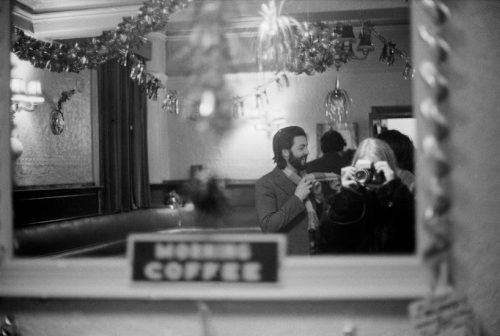

Never one to avoid his own media coverage, Paul was captured by Linda – that’s her name, I promise – checking out (we think) this December 13 issue of Diário Popular on the beach. You’ve seen it elsewhere on this blog, and now you’re going to see it again:

In 2006, Davies shared previously unseen footage at a book festival, just a few minutes of a short 8mm home movie of Paul, Linda and Heather along with his own family during the stay, including a moment from the above media meeting.

Davies recalled the media held their end of the bargain, but for the remainder of Paul’s stay businesses from nearby Lagos tried to lure him with tributes of flowers, fruit baskets and wine left at Davies’ home.

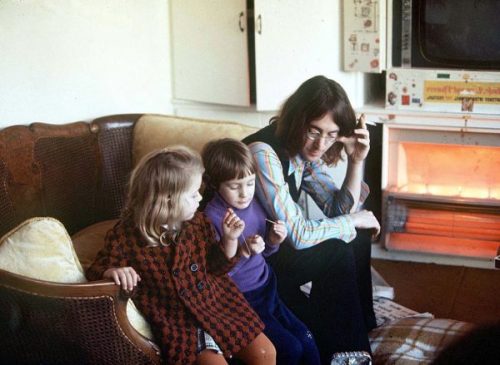

While Paul worked on ensuring the press stayed away from his temporary beachfront residence, John eagerly welcomed the media to his own home. Paul mentioned the possibility of an upcoming television show, but John actively performed for the cameras, including a tiny glimpse into Get Back sessions-to be.

We know Let It Be’s “I’ve Got a Feeling” pieced from two separate songs – Paul’s main section and John’s “Everybody Had a Hard Year.” John’s contribution was written and recorded prior to this date in late 1968, though it’s not clear precisely when. Musically, it’s quite nearly “Julia,” not just the distinctive fingerpicking style, but the guitar’s melody, too. This initial take uses the lyric “everyone” instead of “everybody.”

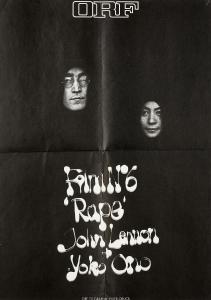

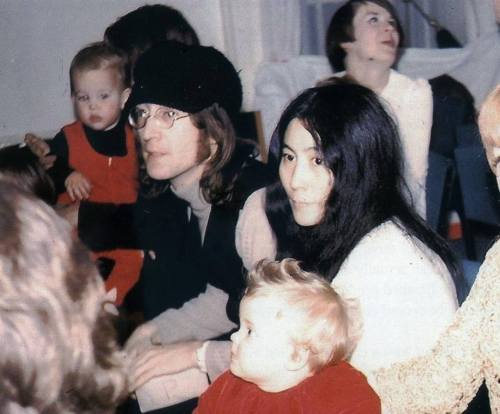

John revisited the song on this Thursday, singing a register lower and in harmony with Yoko. As opposed to the earlier version, we know everything about this one: It was filmed by an Austrian TV crew from public broadcaster ORF (Österreichischer Rundfunk) on the patio at John’s Kenwood estate on December 12, in color on a cloudy day, and later tacked onto the end of the March ’69 Austrian broadcast of the couple’s “Film No. 6 (Rape).” The camera pans across the estate to find John and Yoko seated on a white iron bench, both behatted and in black from head-to-ankles, with white footwear. John is playing acoustic guitar.

The lyrics remain a work-in-progress, but it’s the same gist later used by the Beatles. The song fades in, and you can hear John quickly say “again” as they restart:

Everybody had a hard year

Everybody had a good time

Everybody had a soft dream

Everybody saw the sun shine

Everybody had a hard year

John pauses, points to the camera, nearly touching the lens, and says: “Surprise, surprise”

Everybody had a hard year

Everybody had a good time

Everybody had a soft dream

Everybody saw the sun shine

Oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah, oh yeah

The fine line between this song and “Julia” blurs again, musically. And as quickly as the camera arrived, it pans away from the house and the clip ends.

We can present this is as a tidy metaphor: The day after the Dirty Mac performance of a White Album track, John turned the page and now has his sights set on the next project, or at least on new material bouncing around his head. Perhaps he’s just realizing that as he interrupts himself after a verse: “Surprise, surprise.”

ORF moved operations inside the house, where Yoko hosted a tour of the in-home gallery while John occasionally played a funky little riff on the acoustic guitar. Some of this day’s footage was packaged as part of a documentary on John and Yoko that also aired in Austria in March 1969 (some clips ended up in the 1988 film Imagine: John Lennon as well as in the Beatles Anthology).

Included in the footage is a chess game between John and Yoko on an all-white chess set. “John has a marvelous sense of color and all that, he’s a very sensual artist,” Yoko explains. “I’m not particularly good in using color. White is just to say that you can color it and to say that you can imagine it. It doesn’t mean that I insist on white.”

Presenting items from her Half-a-Wind Show, Yoko invokes the other half of her sky: “A person is a half anyway. … My concept was maybe subconsciously, I was half a person without meeting John.”

Like a lot of events in this narrow period, there are conflicting reports on dates — I should have this disclaimer on every post, really. For instance, the book packaged with the 2021 Let It Be deluxe reissue dated the “Everybody Had a Hard Year” film clip to December 15, 1968. But that’s wrong. I’m trying to get these dates as accurate as they can be and correcting the record where it should be corrected (like the dates of Paul’s Portugal trip).

When it comes to all things John and Yoko, Lennonology is the essential reference, and I’m considering it the authority when there’s any conflict between dates. Co-author Chip Madinger confirmed to me the date of the December 12 filming – it was the second of a two-day visit by ORF, which also shot footage at the Rock and Roll Circus. Likewise, the Internet (among others) wrongly attributes a series of interviews John and Yoko gave on December 14 to December 12. So that’s why I’m not writing about those interviews in this post. (And thanks for the help, Chip!)

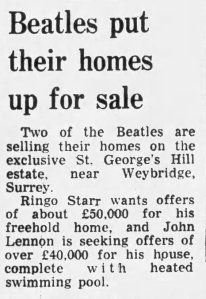

In the wake of his divorce with Cynthia being finalized five weeks earlier, December 1968 would be near the end of John’s time at Kenwood. For at least the last week, newspapers reported he and Ringo Starr had both put their Weybridge estates up for sale. According to AP, John’s asking price was £40,000 (about $96,000), while Ringo sought £50,000 (about $120,000).

There was one other relevant news item involving John and Yoko on December 12. The Ministry of Health issued a statement defending John, who slept on the floor during Yoko’s stay in the hospital when she suffered a miscarriage weeks earlier. In response to a complaint, the Ministry wrote, “Although routine visiting is generally channeled to regular times, when necessary prospective parents may be afforded the facility of remaining together when such a course is considered to be medically desirable.”

George Harrison remained under the radar at the start of December. The Quiet Beatle’s parents, ironically, made news for simply “living quietly.” Per a story in the December 12 Manchester Evening News, with the “hustle and bustle of ‘Beatlemania’ behind them, Louise and Harry Harrison “are seldom troubled by callers and receive only 500 letters a week.” Louise is three months behind, but still responds to all the fan mail.

20 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

Don’t say George Harrison didn’t warn everyone.

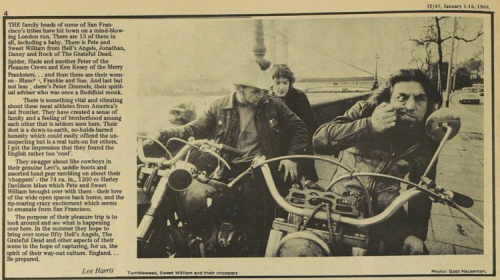

I won’t give away the ending to the story of the Hell’s Angels’ 1968 trip to Apple headquarters — you’ll see it at the end of the month — but if you’re reading this, you probably know it already.

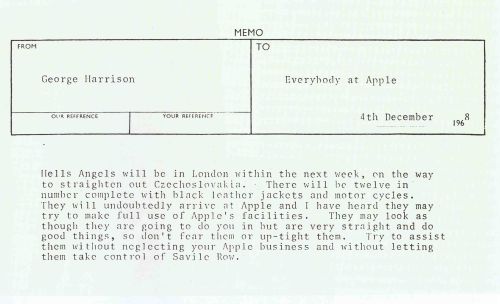

The public never would have known at the time, but on December 4, 1968, George fired off a memo to “Everybody at Apple”:

Hells Angels will be in London within the next week, on the way to straighten out Czechoslovakia. There will be twelve in number complete with black leather jackets and motor cycles. They will undoubtedly arrive at Apple and I have heard they may try to make full use of Apple’s facilities. They may look as though they are going to do you in but are very straight and do good things, so don’t fear them or up-tight them. Try to assist them without neglecting your Apple business and without letting them take control of Savile Row.

A little more than a week later, it was the public’s turn to find out what exactly was going on. Ray Connolly, who so often covered the Beatles beat, shared the news in the December 13, 1968, Evening Standard under the simple headline, “Hells angels.”

Hells Angels, the Californian drop-out society of motor-cyclists, are hoping to extend their activities to Britain.

Two members of the Hells Angels are in London at the moment and have been given an office by the Beatles’ company, Apple. With them are several aspirant Angels and an underground pop group called the Grateful Dead.

To clarify, the Dead were actually in California at the time, but band manager Rock Scully was part of the “California Pleasure Crew” joining the Hell’s Angels in London.

In his 1995 memoir Living With the Dead – written with David Dalton, who co-authored the original Get Back book packaged with Let It Be in 1970 — Scully recounted George’s original invitation to the Hell’s Angels, which happened during the Beatle’s visit to San Francisco in 1967.

On Divisidero he runs into a couple of Hell’s Angels, Tumbleweed and Pete. Wow! Real sweaty, hairy, savage Hell’s Angels. The terror of the West. He’s impressed, all right. They’re impressed, too.

“Fuckin’ George Harrison, man!” In the heat of the moment George invites them to come and stay with him “whenever you’re in London, man.” You know, at George’s house! Now in England, this sort of invitation is taken for what it is: perfunctory politeness. Besides, he must have thought, when are two Hell’s Angels ever going to show up at Saville Row? But this is California, baby! The West—where a man’s word is a man’s word….

“Well, Jesus, George, that’s real decent of you. Real decent. We’ve been planning a trip to check out swingin’ London, haven’t we, Pete?” Pete is equally enthusiastic.

“Fuck, yeah! Hell, we’ll just bring the Harleys, it’ll be a hell of a time.” Whereupon George proceeds to hand them… his card. A bit formal, methinks, but the boys fall on it as if it were a fresh kilo of dope. They hand it around—to sniff, I presume—but on closer examination it turns out to be an Apple Records card. Oh well, he’s not actually going to give them his telephone number at Strawberry fucking Fields, now is he? I mean what if these guys actually do show up?

In time, the guys showed up, bankrolled by the Grateful Dead via Bill Graham.

The International Times reports on the Hell’s Angels’ arrival in England in its January 1-16, 1969 issue.

After arriving and sticking Apple with the air cargo cost of their motorcycles, the Hell’s Angels arrived at 3 Savile Row the next day.

“House hippie” Richard DiLello’s account in 1972’s The Longest Cocktail Party probably stands as the definitive account of this era. It’s a breezy, must-read, so do so if you haven’t already. Here’s how he described the Hell’s Angels’ arrival:

In actual fact, the anticipated, 12-strong army of leather and chains that was on its way to Czechoslovakia to straighten out the explosive and highly degenerate political situation had somehow been watered down to two genuine, dyed-in-the-Levis Hell’s Angels and 16 California freaks: zonked, wired, and suffering from massive time displacement and cultural shock. The two Hell’s Angels were Billy Tumbleweed and Frisco Pete of the San Francisco chapter of the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club, California, USA.

Apple office secretary Chris O’Dell dedicated a short chapter of her 2009 autobiography Miss O’Dell to the Hell’s Angels visit. Like any good host, the first thing Apple supplied was beer, and figurative keys to the building. From Miss O’Dell:

Sufficiently juiced, the Angels started casing the joint, peeking behind doors, opening closets, running up and down the stairs, playing with the elevator, and before long they found their way up to my office on the fifth floor.

So why did the Hell’s Angels really come to London? It depends on when you asked. Per Ray Connolly’s December 13 report, Frisco Pete (Pete Knell) said the plan was to “arrange a party or a dance here for about 50 to 100 of our members.”

In the January 4, 1969, issue of DISC and Music Echo, however – and by this point they had been thrown out of Apple — an unnamed Angel sounded a more ominous tone.

“They were, they said, worried about the power the Beatles had and exactly how they are going to use their influence over the world,” according to the story.

But here on our timeline, it’s only December 13. We’ll hear more from the Hell’s Angels again before the end of the month.

(It’s worth marking that at the exact same time all of this was happening at Apple, three chapters of the Redditch Hell’s Angels lived in the basement at Rutle Corps.)

The Hell’s Angels weren’t quite to Czechoslovakia yet, but Paul McCartney’s Continental adventure continued. At this point, we know some of what he did on his Portuguese holiday, but we don’t necessarily know when.

Paul’s brother Mike (aka Mike McGear of the Scaffold) and wife, Angela, were expecting their first child imminently back in England. Paul picked up some practice on how to be Fun Uncle with Hunter Davies’ kids, doing things like letting 4 ½-year-old Caitlin sit on the Beatles’ knee and steer the car, according to the writer’s memoir “The Beatles, Football and Me.”

“He would also let Jake play with a kitchen knife,” Davies wrote, “refusing to take it off him, saying he would learn it was sharp when he cut himself.”

That’s just the sort of Beatle behavior the headmaster of Clark’s Grammar School in Guildford was afraid of, as published in the December 13 issue of the Surrey Advertiser. Col. A. C. M. Rowlands was up to here with the Fab Four, and let the parents at the school know about it at the annual speech day.

Here’s what the headmaster had to say, under the headline “Homework more important than the Beatles”:

“One understands the attraction to the young of the Beatles and other so-called pop groups when their performance comes just at the time your sons and daughters should be doing their biology or mathematics homework.

“But in these two particular contexts you can, instead, guide your child’s mind along the channels that firstly, a beatle, in biological language, is really a Coleoptera — it’s only similarity to the aforementioned individuals perhaps being that it also is regarded by some as a pest.

“And that, secondly, as far as mathematics is concerned, the Beatles’ theories on ‘All our loving’ are of far less importance than Pythagoras’s theory of “The Square on the Hypotenuse” — even if, in giving this parental guidance, you risk being regarded temporarily as the very personification of that square.”

In some schools, the Beatles could still be role models.

19 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

John Riley is the star of the biggest Beatles-related dentist story, which happened in 1965. Riley covertly dosed coffee with LSD sending dental patients George Harrison and Pattie Boyd as well as John and Cynthia Lennon on their first trip. Riley went down in history as that “wicked dentist,” in George’s words.

Then there was the “Gordon the Irish dentist,” who was anything but wicked when a Beatle and friends spontaneously visited a small town in Bedfordshire. The genial bearded dentist welcomed Paul McCartney, plus Apple execs Derek Taylor, Peter Asher, Tony Bramwell and reporter Alan Smith into his home in Harrold one June day in 1968, serving his surprise guests “hams and pies and multi- jewelled salads, new bread and cakes, chicken and fruit and wine” (by Taylor’s account in “As Time Goes By”).

None of this is to say Dr. Anthony Halperin wasn’t an interesting figure. It’s just his brush with Beatles history was less about him and more about his space.

Yoko Ono is interviewed by Dutch television in a dentist’s waiting room on December 14, 1969. Photo by Susan Wood.

And that brings us to December 14, 1968, when John Lennon had a bridge replaced in Dr. Halperin’s dental chair in Knightsbridge. The real action was in the waiting room, though, where Yoko Ono hosted a true multimedia event: a longform conversation filmed for television which largely doubled as a magazine interview for a separate publication and a photo session for a third media outlet.

As I mentioned earlier in a separate entry, this dentist office interview has often been misattributed to December 12. John could be a little crazy, but he’s probably not “stay at the Rock and Roll Circus until 5 a.m. and then have non-emergency dental work a few hours later” crazy.

We’re lucky to have like the entirety of the interview for the Dutch VARA-TV program “Rood Wit Blauw” (Red White Blue), as conducted by sociologist Abram de Swaan online.

(This YouTube clip is shorter than the audio, and mostly overlaps with the final segment)

While John was undergoing the procedure, Yoko owned the stage by herself and early in the interview defined herself.

I’ve always been a freak, in a sense that even now in newspapers, they don’t know what to call, what to say about me. So they sometimes say, well, a Japanese actress, Yoko Ono, or a film producer, or a composer, or a painter, anything they say. But it’s very difficult to label a person, and nowadays, art is so complex that you can’t label somebody really …

Have you ever tried your hand at describing yourself, somehow labeling yourself, like a bottle sticking a label on itself?

I never bothered to. So I always say, whatever people think, whatever you think, is me. And that’s true.

But you see, in my field, my own field, which is art, I was always considered somebody who is a little bit out of the group, out of everything. So that they didn’t know how to label me, you know.

…

The painter said, well, she’s not really a painter. And the composer said, no, she’s not really a composer.

So I was always out of the circle by trying to, sort of deal with the future and all that. And John was always doing that too, you see.

The segment touched on Two Virgins, recapped the couple’s origin story, the butterfly effect, nudity and the nature of her art.

It’s not the age of professionalism. And the reason why I’m doing these things in my work, all my paintings and all my sculptures are unfinished. And the Two Virgins record is called Unfinished Music, you see. And that is because I want people to finish it or go on adding something to it, so the piece will always go on growing, you know.

John joined a little more than halfway through the interview, “out of [my] skull, out of [my] mind” from the dentist’s anesthesia — at least he knew he was being drugged this time. As described in the March 1969 Nova:

A small ripple passed over us when a third assistant came out of the surgery to announce that “John’s bridge fits perfectly,” but it seemed to be more professional excitement than anything else. “What a miracle that bridge fits” one white-coated girl said to me. “He’s always cancelling his appointments and teeth shift with time, you know.”

Nova further described the shift at John’s arrival:

The microphone approached like an ice-lolly, the Look photographer, having stood in every possible corner of the room, now climbed on a table; and suddenly the door opened and all eyes, all machinery, all attention flew to John Lennon.

…

As soon as John entered the room, Yoko’s lacy self-confidence was replaced by a shy, maternal attitude, she seemed to defer to John who was talking rapidly, to beam upon him; and I realised, heaven help me, that this was going to be a love story.

There seems to be a pact between John and Yoko, probably instinctive and unspoken, that when the conversation is about art and the arts Yoko is set loose like a pretty moth; anything else, taxes, politics, police raids, is John’s province.”

The topic shortly went to their recent drug bust at some length (“we were lying in bed feeling very clean and drugless”) before an involved discussion of taxes and materialism and prejudice. That last topic led to a some provocative quotes from John and Yoko, especially read in 2023. It also was the first public mention of a phrase that would later serve as the title of a controversial 1972 single.

John: I believe in reincarnation, right? So that’s one thing that helps me in an overall view of things. I believe that I’ve probably been black, I’ve probably been Jewish, I’ve probably been female, I’ve probably been a tree or anything. And that helps a lot. So a lot of sort of intellectual reincarnation.

But even so, you can make it, you know, it might be tougher physically and materialistically to make it being black and that. But you can make it, you know. And I sympathize, and I think it’s terrible. I believe it should be smashed one way or another, people’s prejudice, but they won’t change it really by violence. Okay, so the black power scene, you know, good luck to it, because at least it’s frightening them. It might frighten them enough to kill them and have a real war.

OK, so then if the blacks took over, all well and good, but all the blacks aren’t saints. You know, it’s going to be the same scene, just a different version.

Yoko: For instance, I believe that the situation of the women in the world is today, it’s like a woman is like the nigger of the world. And so that’s why we understand about the nigger problem very much.

For a bit of context, the interview aired on Dutch TV on January 15, 1969 – right as the Get Back sessions were reaching a standstill. The Nova interview was in the March 1969 issue, and the photos from Look appeared in its March 18, 1969 edition. Either the Austrian television crew from the other day was still lingering or they managed to get their hands on the Dutch footage, but some of the dentist waiting room film made it into their documentary, too.

John and Yoko hold court in the waiting room of his dentist. Photo by Susan Wood.

One easter egg from the footage and Look’s photos: John wears the same shirt to the dentist as he does to rehearse and record during Get Back (and record “Hey Jude”).

But on December 14, 1968, as far as the public was concerned, the next Beatles project was an imminent concert.

By this point, it was no longer will the Beatles stage a live concert, just when and where. We learn in the Let It Be/Get Back experience that these questions weren’t so easily answered and went down to the last moment. By mid-December we knew the show would end up in the new year, and as far as venue, it wouldn’t be London’s Roundhouse.

The December 14 DISC and Music Echo reported another possibility that the Beatles touched on and mooted during the Get Back sessions, perhaps the venue they knew best of all: Liverpool’s Cavern Club. This grew out of what was probably a late October visit by Paul to the Beatles’ old haunt.

When Paul McCartney made a nostalgic visit to his hometown recently he expressed a strong desire to appear there again with John, George and Ringo.

…

Said club’s owner, Alf Geoghan, to whom Paul spoke: “He didn’t definitely state that they would come. But he did express a desire to play again.

“He seemed quite delighted to find the place comparatively unchanged. He says he expected padded walls and Japanese waitresses!”

Paul spent two hours at the Club, according to the story, which closed with a characteristic give-every-answer-at-once reply from Apple publicist Derek Taylor:

“The idea of the Beatles playing the ‘Cavern’ again isn’t as bizarre as it seems. We won’t say POSSIBLY or PROBABLY. But it’s very attractive.”

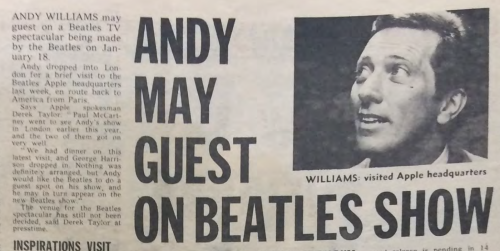

Meanwhile, Melody Maker speculated on another rumor that never came close to coming true, writing in its December 14 edition that Andy Williams could be a guest on an upcoming Beatles special, which they pinned down with a January 18, 1969, date. This came on the heels of the American crooner meeting with both Paul and George during the course of 1968.

“Nothing was definitely arranged,” Taylor told Melody Maker. “But Andy would like the Beatles to do a guest spot on his show, and he may in turn appear on the Beatles show.”

Both the Cavern and Andy Williams speculation were laid to rest at by the end of the month, when the January Beatles Book magazine hit mailboxes, saying “Rumours that the programme might be made in Liverpool instead of London have been denied. So has the idea that Andy Williams, who lunched with Apple executives a few weeks ago, might make a guest appearance in the show.

While talk of a live Beatles show ran rampant, a new theory emerged that they had another studio release besides the White Album already in stores. From the appropriately labeled “RUMORS” column in DISC and Music Echo:

That unknown group, the Moles – whose “We Are the Moles” getting a lot of airplay – is really Beatles in disguise. Anonymous caller summoned by DJ Stuart Henry to London’s Hyde Park offering exclusive interview. Says Stuart: “I was met in a taxi by a person dressed from head-to-toe in black. He even had a hood on. I’m not convinced – but it could have been John Lennon. The record certainly sounds like the Beatles.”

The Moles never actually charted with “We Are The Moles,” which was released in mid-November 1968. Of course, they also weren’t the Beatles, but instead were British psychedelic pop band Simon Dupree and the Big Sound in disguise. Shortly after this entry in DISC, the cat was let out of the bag by none other than Syd Barrett.

Here’s how it all went down, according to a recent interview with Derek Shulman, who was the lead singer of (and would later help form) Gentle Giant:

We didn’t know that in the studio at that time, Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd were recording as well. And when the buzz started to happen and people were saying, ‘Wow, it’s a Beatles song, they want to call themselves the Moles, we got to buy this.’ Syd did a big interview saying, ‘No, it’s not the Beatles, it’s the shitty band Simon Dupree, so he blew the whistle on us.

As the Moles stalled on the charts in emulating the Beatles, it was really enough to simply cover them, and one song in particular. No fewer than The Bedrocks, Joyce Bond, Chris Shakespeare Globe Show, Arthur Conley, Marmalade and Spectrum all had covers of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” on the market (and of course, the Beatles’ own version LP-only in the UK and US). Paul later revealed the Bedrocks’ version was his favorite during a January 13, 1969, conversation at Twickenham.

The early winner in the “Ob-La-Di” sweeps was Marmalade, who entered the charts at No. 22. A lengthy feature in New Musical Express spotlighted the band as they began a journey that would lead to an eventual UK No. 1.

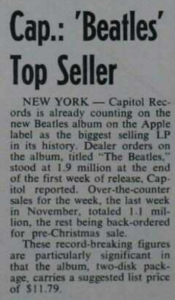

Whether it was an imposter like the Moles, or imitators covering Beatles tracks, nothing beat the real thing. In the December 14, 1968, issue of Billboard, Capital Records said the White Album was in line to become their biggest record in the label’s history. After just one week, dealer orders already stood at 1.9 million while over-the-counter sales totaled 1.1 million.

This kind of success would help subsidize a new experimental label publishing budget-priced LPs featuring “talk, poetry and music especially designed for the college market,” as Billboard described a what would become Zapple, a few pages later in the same issue.

And that takes us back to John Lennon. If you thought bridge work was a pain, try selling a record with a naked photo of you and your girlfriend. Another Billboard article laid out the situation with Two Virgins and American music store chains. While distributor Tetragrammaton planned packaging that would obscure the cover’s nudity, five stores flat-out refused to sell the LP: Sears, White Front, May Co., Broadway and Wallichs Music City.

“We don’t carry any product that might harm our reputation as a family store,” Sears said in a statement, and Billboard added the company probably wouldn’t change its policy even with new, more modest packaging.

In denying sales of the LP, a May Co. representative said: “While it’s not our job to act as a public censor, I feel sensationalism and liberalism can go too far.”

One chain, though saying they wouldn’t sell the record with the nude cover in its “raw state,” committed to selling the LP, and gave the right reason.

“An artist of John Lennon’s stature is too important not to be heard,” said a merchandise manager from Korvette’s. “Appropriate arrangements are being made to handle the LP and still not offend our family trade.”

18 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

Several recollections and artifacts of Paul McCartney’s December 1968 trip to Portugal exist today, but one thing we lack is a clear timeline of his day-to-day activities. There’s no diary, no printed itinerary. We do know the kinds of things he did – spending time at the beach, visiting local towns, hiking in the mountains. It’s mostly based on Linda Eastman’s photographs or Hunter Davies’ written memoirs.

The most enduring document of the trip is a song. “Penina” wasn’t the first song with a “McCartney”-only songwriting credit – the ’67 Family Way soundtrack holds that distinction – and it was never formally recorded by Paul or the Beatles. But “Penina” is one of the few tangible things sprouting from the trip, between several recorded versions by a variety of acts, a newspaper story about the Paul giving a song away as “a £20,000 holiday tip” and a resultant, ragged performance of the song during the Get Back sessions.

I’ve written up the origin story of “Penina” at some length before, but let’s quickly recap the basics: One late night during his Portuguese holiday, Paul showed up drunk (by his own account) at a hotel in Alvor, reportedly to exchange some currency. The house band, Jotta Herre, was performing at the hotel bar in the early hours, and Paul accepted an invite to hop on stage. Here’s Paul’s account of what happened next, as he told the other Beatles on January 9, 1969:

And I sat in on drums, and they said, ‘Give us a song.’ So I said, OK.

[Singing] I’ve been to Albufera, had a great time there

It was called La Penina, the hotel. And they were all digging it and singing along, and it was good.

The January 9, 1969, Daily Express story, which first mentioned “Penina” to the public, quoted Beatles publicist Derek Taylor downplaying Paul’s gift of music, saying “this was not a whole song he gave to the bandleader. It was more a rif.”

But, as the paper continued:

Northern Songs shareholders in fact are presently benefiting from a rif, “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” John Lennon and Paul McCartney borrowed – from another performer, Jimmy Scott.

Paul was furious in reading that January 9 report, saying his offering of “Penina” as a throwaway was no different than his reception and reinterpretation of Scott’s phrase.

“You haven’t got a riff when you say ‘hello,’” Paul said to the other Beatles. “That’s the riff I got off of Jimmy Scott, those two words (“Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”). You’d think I’d taken his life. It’s not as though he wrote the song.”

We don’t know precisely when the “Penina” performance occurred. There isn’t any audio or photographic evidence. In 2021, the hotel offered a reward of a three-night’s stay to the best photo submitted of Paul performing there, but as far as I can tell, no one ever cashed in the reward. Maybe there’s a snapshot somewhere in Linda’s archives.

For the purposes of getting the “Penina” night on my December 1968 agenda, I’m placing it here, on December 15, perhaps selfishly for my own narrative purposes. I’m in no way proving or definitively saying that this is when it happened. But it’s as good a guess as any barring any proof to the contrary. This would have been the early hours as Saturday night becomes Sunday morning (not that days of the week matter much when you’re on holiday), and it’s certainly feasible.

Again, you can read a fuller account of the “Penina” origin story here.

Now let’s tie “Penina” back to “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” again, this time to help clear up some myths about the latter.

The song was sneaking up the singles chart in the UK, not by the Beatles, but releases from six artists clamoring for the top spot. Marmalade had the inside track – see yesterday’s entry for more on that.

On this December 15, 1968, Jimmy Scott earned a small feature in the Sunday People newspaper. This obscure interview presents several insights that challenge today’s established wisdom about “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” But first, a little of what we’ve been led to believe. Stick with me, I’ll get back to this interview, and December 15, 1968, soon.

I’m going to point to the song’s Wikipedia page as published mid-December 2023 because it’s the easiest target to pick on, the top Google search result and presumably the most viewed online resource on the song’s development. But it, the sources it cites and all the websites and publications that repeat this information are incorrect on a few relatively key facts. This isn’t the same as being off a day or two on something. From Wikipedia:

After the release of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” in November 1968, Scott tried to claim a writer’s credit for the use of his catchphrase.[15][6] McCartney said that the phrase was “just an expression”, whereas Scott argued that it was not a common expression and was used exclusively by the Scott-Emuakpor family.[12] …

Later in 1969, while in Brixton Prison awaiting trial for failing to pay maintenance to his ex-wife, Scott sent a request to the Beatles asking them to pay his legal bills. McCartney agreed to pay the amount on the condition that Scott abandon his attempt to receive a co-writer’s credit.[18]

Now let’s get into what Scott said in the December 15, 1968, Sunday People interview, as reprinted above, here with my emphasis:

POP MUSICIAN Jimmy Scott told yesterday how a catch-phrase and a Beatle’s generosity saved him from a long term in prison.

Jimmy, who used to play the conga drums with Georgie Fame, was jailed for failing to pay maintenance to his wife. If he could find the £139 he owed he would go free.

He had served a week in jail when Beatle Paul McCartney heard of his plight — and paid off the £139.

And one of the reasons for Paul’s action is that Jimmy inspired the song ” Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da,” the biggest hit on the Beatles’ new album.

For years, 38-year-old Jimmy would say farewell to his friends with the phrase: “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da – life must go on, bra.”

Explained Jimmy: “Ob-la-di is a word I made up from Afrikaans and I’ve used it for nearly 10 years. “Paul asked me if he could use Ob-la-di as the basis of a song for his new album. “He has written a completely new melody and all the words are different—except those seven in my farewell phrase.

“I agreed he could use the words and he invited me to the recording studio to listen to the song. Then I gave him the correct spelling of the title.”

…

Said Jimmy: “He has never asked for any of the money back.”

This contemporary account exposes a few key issues with the accepted knowledge surrounding Scott’s relationship to the song. While we know Scott complained about credit for “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” — Paul mentions it on several occasions in the January 1969 Nagra tapes — in December 1968 Scott himself admits the quid pro quo. Paul made the deal — charity, perhaps — before the song’s release and success.

(Jimmy Scott plays conga drums on an early take of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”)

Your mileage may vary on where you draw the line on cultural appropriation, but there’s a big difference between Paul using a phrase that was part of Scott’s Nigerian family heritage and a word Scott admitted he “made up” and used for only the last decade.

Paul gets a little bit into the agreement with Scott in 1997’s Many Years From Now (as later reprinted in the book packaged with the 2018 White Album deluxe reissue):

He was a great guy anyway and I said to him, “I really like that expression and I’m thinking of using it,” and I sent him a cheque in recognition of that fact later because even though I had written the whole song and he didn’t help me, it was his expression.

That memory seems in line with Scott’s interview published December 15, 1968.

***

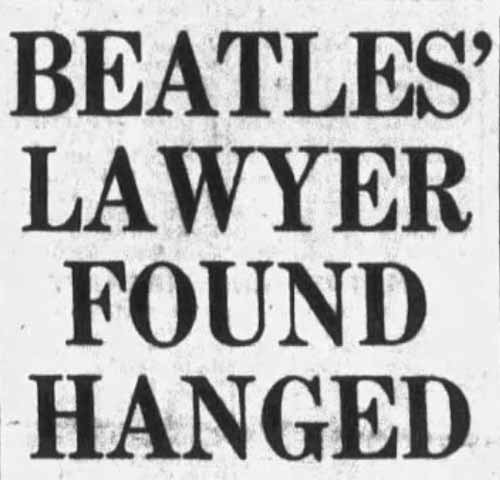

It was front-page news the next day. Celebrity lawyer David Jacobs, 56, was found dead, hanging in his garage at 4:30 p.m. at his Sussex home on Sunday, December 15. News reports said he was recently in ill health and had suffered a nervous breakdown.

Jacobs was the lawyer for Beatles manager Brian Epstein, and while not necessarily a villain in their story, to a large degree he earned responsibility for the horrendous merchandise deal the Beatles were signed to at the height of Beatlemania.

At this point, the death was a mystery but police said they did not suspect foul play.

Sir Laurence Olivier, Judy Garland, Marlene Dietrich, Shirley Bassey, Donovan and Liberace counted among what the Daily Mirror said were his 5,000 clients. “He was the lawyer for almost every big pop group in the country,” according to the paper.

Jacobs was a celebrity lawyer, and a lawyer that was a celebrity. A piece in the December 16 Evening Standard elaborated:

David Jacobs was one of the very few non-political British lawyers to achieve fame in his own right. His services, for any pop star or actor in trouble, were de rigueur.

…

During a decade in which lawyers tentatively emerged from anonymity, David Jacobs stood out as a rare, exquisite (a colleague’s adjective) public advocate, one who was subject to the same prominence as his clients. He was therefore exposed to the same sour grapes, the same skepticism, as well as the same glamour.

Even with his role in costing the Beatles millions and millions of dollars, the Beatles maintained a friendly relationship with Jacobs. Ringo Starr honeymooned with Maureen at Jacobs’ house — the same one the lawyer was found dead in — in 1965.

On the news of Jacobs’ death, the Beatles issued a statement: “He was a great friend to all the Beatles and of course, to Brian. He was always there when he wanted him. He was a very steadfast man.”

17 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

Last week had been a doozy for John Lennon and Yoko Ono, busy with added crazy: rehearsals then a return to the stage at the Rock and Roll Circus, a late-night radio appearance, multiple interviews at a dentist’s office on the heels of bridge work for the Beatle. Plus the couple had brief custody of young 5-year-old Julian, while his mom was on a vacation with her significant other.

December 16, 1968, was a Monday, and a good day to stay in. But a Beatle’s work is never done.

Nova writer Irma Kurtz spent the day at John’s Weybridge estate – she wrote his “castle is protected by nothing more menacing than a sign, and it could be called significant, which says: ‘Children Playing’” — wrapping up reporting she began two days earlier at the dentist’s office. These interviews would eventually be published the following March.

John and Yoko continued to be in promotional mode taking the interview at their home, but after a week of so much hustle, we can revel in this documentation of the mundane.

For instance, these were crazy cat people, owners of “eight beautiful cats who warm themselves at the cooker between getting pregnant and, unlike the rest of their household, being carnivorous.”

Yoko worked in the kitchen, slicing leeks “with the artistry of a sea-cook,” tossing the vegetable in butter.

‘I feel that I’m getting younger. Even physically. It is partly the diet because, you see, you are what you eat,’ she said with a confidence that would astonish a biologist. ‘And it is also the fact that I have met John. This year has been hard.’

Maybe with the couple working at such a high velocity, thoughts of slowing down easily took hold.

‘We’re looking forward to our retirement,’ John said, stretching his tennis shoes toward the fire. ‘Having created everything we want, we’ll just settle down on a farm maybe. I don’t know if we’ll actually farm.’ added the practical man.

‘I’m still hung up on work; I can’t help working,’ Yoko said. ‘That’s beautiful, but’ she added with one of those butterfly leaps so difficult to make coherent, ‘if I get over it, it will be better. All this hassle! Then we’ll just be together,’ said the romantic from the East.

Yoko touched on the lows of the past year, specifically the recent drug bust and miscarriage.

“But it is like a game,” Yoko said. “Everything is like a game if there is somebody else, and now I have John.”

John, Julian and one of Julian’s friends enjoy the afternoon at home on December 16, 1968. (Photo by Bob Thomas)

And for this brief period, Yoko and John had Julian, in what probably was the last week he got to spend in the house he was first raised in.

We’re blessed not only with descriptions and quotes from this day, but also photographs courtesy of Susan Wood and Bob Thomas. Just like he did during the Get Back sessions, John opted to wear “continuity clothes,” the same beautiful, and questionably laundered rainbow shirt he had on at the dentist’s office 48 hours earlier.

John is captured in one photo with a newspaper, a treasure to a researcher hoping to confirm a date.

The couple went outside for additional photos with John’s Rolls Royce and big, black hats, as one does.

About 1,500 miles away, Paul McCartney was near the end of a holiday in Portugal. Like John, he performed in the past few days, too – but Paul created a circus of his own, drunk at a hotel bar with not a single camera or recording device in sight (see the last entry, on “Penina”). Paul spent a week deliberately avoiding the media.

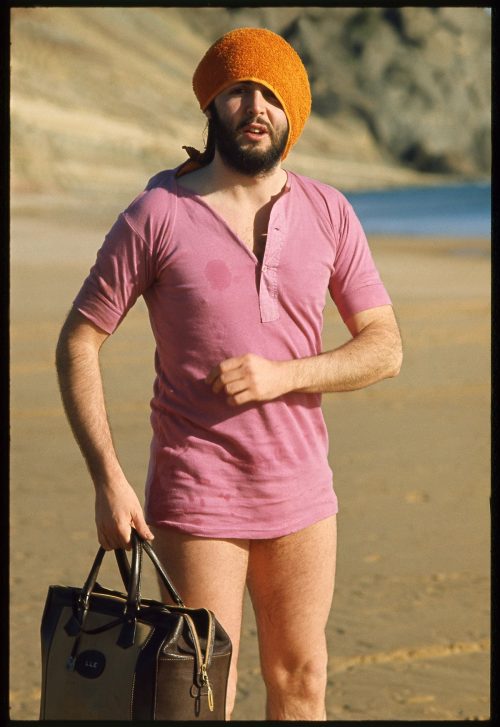

He spent time at the beach, as documented by Linda Eastman and probably first seen by the public in the gatefold of the McCartney LP. All of these subsequent photos aren’t specifically dated, but fall within this week.

We also know he went sightseeing, shopping, outdoor pursuits — that is, the normal things you do on holiday.

Paul, who hates socks, tries to take a photograph despite Heather Eastman’s objections, as Caitlin Davies looks on. Portugal, December 1968.

It wasn’t entirely play for Paul. According to Hunter Davies, and as recollected in his memoir “The Beatles, Football and Me,” Paul began writing a novel.

He borrowed my typewriter, when I wasn’t using it. I did try to sneak a read at the odd page, behind his back, but didn’t manage it. (I have asked since about his aspirations to write a novel, as he has now done a book of poems. He says he has completed a work of fiction, but it’s locked in a safe while he decides whether to have it published or not).

When Paul vacationed in Portugal in 1965, he forgot his guitar. Not so this time.

“In odd moments, including going to the lavatory, we could hear him playing away,” Davies wrote.

16 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

We’re not entirely sure when Paul McCartney truly concluded his holiday in Portugal, but December 17, 1968, is my best guess.

Hunter Davies, who played host to Paul, Linda and Heather Eastman, wrote decades later that his guests stayed two weeks. Contemporary press published the day after Paul arrived said they planned an eight-day stay, while the January Beatles Book magazine said he was away for a week. Depending on whether you count his late-night arrival as a day or not, December 17 would either be the seven- or eight-day mark. Maybe he left the next morning. The calculation is vague enough to work.

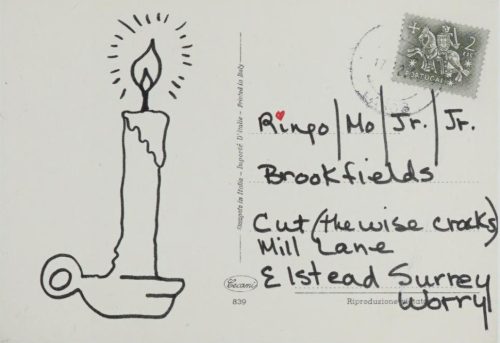

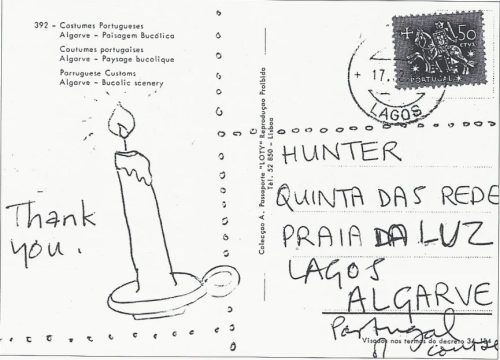

There’s more definitive evidence Paul journeyed to the post office this Tuesday – or at least visited a collection box — dropping a pair of postcards in the mail.

The cards shared two identical features: Both were embossed with a “17.12.68 LAGOS” postmark over the stamp, and each card featured a hand-drawn candlestick in black ink on the left side.

One card was sent to the Starkeys – “Ringo/Mo/Jr./Jr.” at “Brookfields, Cut (the wise cracks) Mill Lane, Elstead Surrey Worry.” Still, the postcard reached them just fine. Decades later, when it was reprinted in his book Postcards From the Boys, Ringo added the caption: “From Paul and Linda. Nice picture! Those guys had a lot of holidays!”

Paul sent Hunter Davies a similar postcard, though the images on the front must have been different since the back had different photo credits. In addition to the candlestick, Paul added “Thank you.” Davies’ address was written properly except for Paul added “of course” after “Portugal.”

The postcard offering thanks to his host is exactly why I think this day marked the end of Paul’s trip.

Paul’s postcard wouldn’t have reached Ringo for several days yet, but December 17 was a milestone day for the drummer. Ringo wasn’t in attendance for the black-tie affair at the Astor Theater in New York, but on this date, “Candy” – which featured his first acting role outside of a Beatles movie – enjoyed its world premiere about a year after his part was filmed.

The gist of contemporary reviews was that “Candy” was essentially a farcical stag film with an all-star cast. Ringo’s role was small – Emmanuel the Mexican gardener – but his own star(r) was big enough the studio marketed off his name (in addition to the others).

On January 13, 1969, while waiting for the others to arrive at Twickenham, Ringo spoke at some length with Michael Lindsay-Hogg about his experience filming “Candy.” At one point, Michael asked Ringo if he preferred drumming to acting.

Ringo: Well, it’s hard to say, doing so little movies and such a lot of the drums. “Help!” and “A Hard Day’s Night” was all right because its the four of us and we played, and did it. The only trouble with those [was] when I didn’t know what I was doing. … So I did ‘Candy’, which was only two weeks — which was great because I have to do something. …

I thought it came out very well. …

MLH: Did [director Christian Marquand] help you?

Ringo: No, I didn’t feel he really helped me. I thought I found I played it after reading the book how I thought he should be. And that’s the only disappointing thing. Because if you haven’t read the book, when I watched it, I played it all sort of nervous and shaky, because in the book the gardener is terrified. But in the film it just looked a bit strange where I come in all shaky and nervous. If you haven’t read the book you don’t know why.

…

[I had a] Mexican [accent], which I’ve lost now, because I’m not very good at accents. And we have to have this coach there, kept telling me to speak like a Mexican, and there was a Mexican guy there to help me.

That conversation soon steered to his next film project, another Terry Southern book adaptation: The Magic Christian.

Ringo’s reputation as an actor already had some traction, certainly by comparison to another certain Beatle. Don’t expect any scripts waiting for you at home, Paul.

From Sheilah Graham’s syndicated gossip column “Movie Gadabout’s Diary,” as published on December 17:

Paul McCartney, the most popular of the Beatles, according to a recent British poll [on December 10], is the best singer but the worst actor in the quartet. Which perhaps explains why he has not received offers to work solo in pictures, a la Ringo and John Lennon.

15 days until the start of the Get Back sessions

It was the dawn of Bagism.

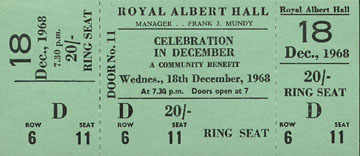

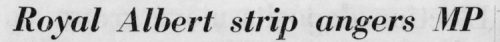

The Royal Albert Hall played host to the Alchemical Wedding, a benefit for the Drury Lane Arts Lab, a multimedia exhibition space for alternative arts.

Somewhere between 600 and 3,000 people (contemporary accounts vary widely) reportedly attended the “Celebration in December – A Community Event” – which sounds more like a Christmas tree lighting in the suburbs than the event that took place.

David Mairowitz set the scene in the January 1, 1969, issue of International Times :

So the Albert Hall was booked, thousands arrived, not one with a clue as to the evening’s events. There were rumours of Leonard Cohen, the Beatles, the Stones showing … Such promises of glory.

There was, however, one Beatle in attendance. We’ll get to him soon.

The event presented several acts on stage: poets, Hare Krishna chanting, musicians.

Hey, John Lennon is a musician, and he was there!

This is true. But even before John took the stage, the big news coming out of the evening unfolded not on stage but in the audience. Remember a week earlier, when John and Yoko Ono appeared on BBC, and in promoting this event, Yoko said “go naked”? (See the December 11 entry.)

From the front page of the December 19, 1968, Daily Mirror, under the headline “The girl who stripped off at the Albert Hall: Police called to a ‘happening’ in the audience”:

Blonde Elizabeth Marsh sits serenely in the audience at the Royal Albert Hall … without a stitch on.

She stripped off her ankle-length black dress last night when Indian music was played during a “hippy happening” at the hall called “An Alchemical Wedding.”

Then 24-year-old Elizabeth, from Texas, sat completely naked in the third row while hall official pleaded with her to get dressed.

But some of the 600-strong audience formed a human shield around Elizabeth – and started to take their clothes off as well.

A UPI wire story published two days later fleshed things out further:

“It was the funniest thing you ever saw,” said Jack Henry Moore, of Sulphur, Okla., co-director of the art theater group which sponsored the happening …

Moore said at least 50 men and at least one woman had taken off all their clothes above the waist by this point to show their solidarity with Miss Marsh.

[Co-director Jim] Haynes, of Haynesville, La., said Miss Marsh’s “thing” was one of the high points of his $2.80 a ticket “happening” staged to raise funds for his Art Laboratory Theater.

…

“I don’t know why I did it, but there were good reasons at the time,” [Marsh] said.

This offstage act served as an opener for who would serve as the headliners: John and Yoko. But there was no poetry, no music. And if you wanted to see these two naked, you had to go to the record store.

The couple walked on stage and subsequently entered a white bag. And they were there, but gone, for a half-hour. Here’s a lengthy account from the January 1, 1969, International Times:

Finally, John Lennon and Yoko Ono came out in black robes and disappeared under a white-sheet sacking. Nothing happened. Simplicity was having its day. Another Void. Another filling up. Every fourth member of the audience had his say, a mass hysteria of John Lennon jokes. Then a lousy poet read some lousy poetry. In the midst of all this, the glorious moment of the evening occurred. Someone bound in a white sheet threw himself off the stage into the pit. Finally we were not being conned. It seemed a pure act of madness. It was savage tortured meat hurling itself among the vague love children transfixing each other on a spread of cloth. Perhaps. Only Perhaps.

John and Yoko emerged after about half an hour, fully clothed, again WE were the event. The lights came on, but then a specrte of fury and wrath poured down into the abyss. On its neck was an enormous hand-made sign saying The End of the World is at Hand for 7,000,000 people in Biafra. It approached, the symbol of the Death of the Evening, imploring John Lennon to cease his interest in making money and speak out on behalf of Biafrans. One’s first impression was it was part of the show. But no, such a military downer, it was unlikely. Rather the bloated conscience of England, hidden somewhere in the Victorian rafter of the Albert Hall, appeared as God from the Machine to bring the levity of England’s children to a halt. John Lennon was gone by then, but wouldn’t have replied anyway. And who could? One only wished the rock group called the Sun would come back immediately and ‘accompany’ his plea.

A flautist, Neil Oram, was on stage while John and Yoko were in the bag, and performed. As he recalled in Lennonology:

People were booing, and they were calling out for me to read and play my flute and read my poems. And after an half an hour, they were inside this fucking bag, then they got out to people booing them and everything and John Lennon was really pissed off. I don’t know why they turned up with such a boring stunt at such a fantastic event.”

I had no idea what they were up to, and then they got their bag out and got inside it.

Wire accounts said otherwise, that they “were applauded wildly” – but those same accounts said the audience stripped during John and Yoko’s performance, which is false.

John later spoke highly of the event. From a 1971 International Times story, via Lennonology:

It was all a beautiful thing, but very nerve wracking. I mean I was scared shitless going into a bag we couldn’t see out of. It was worse than singing, going on stage and doing that.”

Why get in a bag at all? When they more formally introduced Bagism as a concept the following March, they described it as an example of “total communication.”

Among the members of the audience counted the Hell’s Angels, who were still making Apple their temporary headquarters. (See the December 13 entry for more on their arrival.)