The Last Beatles Song.

Let’s be a little more accurate and say with several qualifiers that it’s the last, new officially released Beatles song. The diehards already knew it from bootlegs, of course.

Not now, but back then, it was some other John Lennon vocal — not “Free as a Bird” or “Real Love” but the group’s 1964 recording of “Leave My Kitten Alone” — that qualified as the first last Beatles song.

“There is other unfinished recorded material of the Beatles which has never been released but ‘Kitten’ is the only complete track,” an EMI spokesman (presumably Brian Southall) told the Daily Mirror in September 1981. That same story said John’s death derailed initial plans to release the song as a Christmas 1980 single.

If you’re looking for a sign of the times and an indication of how much the coordination between the label and band have changed in 40 years for legal reasons and otherwise, here’s another quote from EMI:

We don’t need anybody’s permission to release the record because it was made for us before the Beatles set up Apple, their own recording company. But we would probably inform Paul McCartney who is still with us.

(George Harrison and Ringo Starr were still with them, too, by the way.)

Further details emerged later in 1981, when an AP report (citing the now-defunct Los Angeles Herald Examiner) said a dozen unreleased Beatles songs were in the vault, but only “Leave My Kitten Alone” would see daylight, probably in 1982 or 1983. Hope we didn’t get too excited back then because …

“At this moment, no, we are not planning to put out anything more.”

Just how do EMI and the Beatles lose a song and recover it years later? Here’s a quick timeline:

- August 14, 1964: The Beatles commit their ferocious cover of “Leave My Kitten Alone” — originally recorded by Little Willie John in 1959 and two years later by Johnny Preston — to tape at EMI Studios. It’s done in five takes, including false starts.

- December 4, 1964: Beatles for Sale is released, and of its whopping six covers, none are “Leave My Kitten Alone.” We don’t hear of the song again in the Beatles career, not even during the Get Back sessions, when they played all kinds of things.

- August 15, 1970: Apple flack Peter Brown tells Melody Maker that there is no unreleased recorded Beatles material. Even then, everyone knew better as Get Back session outtakes, for instance, were already circulating.

- 1976: With the Beatles no longer under contract as an entity to EMI, the label began to take stock of what actually was in the Abbey Road archives, a lengthy process. An in-house EMI compilation of songs that included “Leave My Kitten Alone” eventually made its way into collectors’ hands, and ultimately bootlegs.

This brings us to the early 1980s, and EMI’s admission that the song would ultimately be released.

The emergence of “Leave My Kitten Alone” was tangible and exciting at the time. It wasn’t a fringe bootleg or a brief mention in newspapers anymore. You could hear it on mainstream radio.

Here’s one example: For a solid month in late summer 1984, the song was listed among the “Most Played Singles” on Boston’s WBCN (the same station which happened to be the source of the famed Kum Back bootleg 15 years earlier).

The excitement for the song wasn’t isolated to one market, either. I know because I remember it myself.

That child is going to miss you: My ’80s dub off the radio here accompanied by elementary-school-era scrawl on the label. As you can tell, I save everything.

It must have been some time in that same period in 1984 that one of the local New York radio stations (WNEW? WAPP?) played the song. I was 10, but already a fully formed Fab Four fan. I remember the station’s promotion was breathless — it was the “new” Beatles song, and I’d never experienced such a thing.

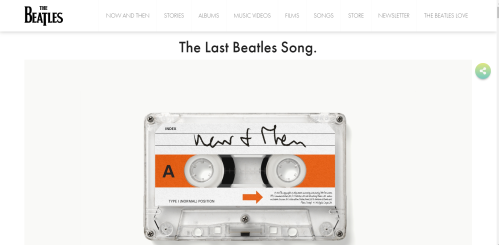

I grabbed a cassette tape not unlike the one central to the 2023 “Now and Then” promotional campaign (mine was Type II though, only the best for the Beatles). I hit play-record a few seconds into the song, and while I thought I was doing myself a favor at the time cutting out commercials, 40 years later, I wish I hadn’t lost the extra context.

By this time, the song’s release dovetailed with that of the compilation, Sessions, which has its own entire backstory. The LP and its lead single, “Leave My Kitten Alone,” had catalog numbers and release dates for early 1985.

There’s some debate if this is genuine or a fake, but it’s definitely some kind of sleeve for a “Leave My Kitten Alone” single.

Suddenly, the entire project was dead, reportedly because of objections from the three living Beatles and the Lennon estate, as well as the fallout from a new lawsuit between Apple and EMI. Like so much else, the Sessions LP lived on in bootlegs, almost immediately. (I had mine on cassette, backed with Get Back.)

It took another decade, after all manner of legal issues were resolved, that Yoko Ono handed tapes of four demos by John — “Free as a Bird,” “Real Love,” “Grow Old With Me” and “Now and Then” to Paul in 1994 for the surviving Beatles to adorn for Anthology.

The technical (as well as critical and commercial) success of Natalie Cole’s “Unforgettable” duet with her late father in 1991 made a Beatles recording with John feasible. Until then, every Beatles reunion suggestion centered around a replacement for John. This ensured the irreplaceable would not be replaced.

This “Kitten” had nine lives, finally hitching a ride with the next last Beatles song — “Free as a Bird” — onto Anthology 1, officially becoming canon 31 years after it was recorded.

And it left the door open for another to be the last Beatles song.