Dave Grohl told a funny story about Paul McCartney on “The Graham Norton Show” during the promotional tour for his 2021 memoir, The Storyteller, expanding on a brief passage from the book itself. The episode played out in 2014, when Paul and wife Nancy Shevell visited Grohl to meet his newborn baby and indulge in an evening of pizza and wine.

There’s a piano in the corner of the room and [Paul] just can’t help himself. … He starts playing “Lady Madonna” in my fucking house. And my mind is blown. I can’t believe this is happening. …

[Grohl’s 5-year-old daughter Harper] had never taken a lesson to play any instrument at that point. And she sat down and she watched his hands. They sat together, and he was showing her what to play. And they wrote a song together. …

The next morning, I woke up and I went to the kitchen. I was making breakfast, and I heard her playing the song that they had written the night before. And I came around the corner, and she looked at me as she was playing the piano. She realized I was watching, and she never played the piano again.

And then she’s like, “I want to be a drummer.” I’m like, “Are you out of your mind?”

The anecdote is relevant not because – in an outstanding coincidence – Grohl was born on this January 14, 1969. Instead, the story underlines Macca’s actions to start his own day, thousands of miles away, on the same January 14, 1969.

“The great thing about the piano is, like, there it all is, there’s all the music ever,” Paul told 22-year-old clapper loader Paul Bond. “That’s it. All the music that’s ever been written is all there, you know.”

(Going forward from this point, when I call someone just “Paul,” it’s McCartney.)

In the midst of a discussion of various music styles, Paul followed with chaotic cacophony on Twickenham’s Blüthner as a demonstration of “the latest things in music,” conceding “that’s music too.”

This sequence is short, but we can glean quite a bit from these five minutes of the two Pauls interacting in real time as recorded on the Nagra tapes (it’s only two minutes in Get Back). An incident like this opens up the space to tell the Beatles’ life and career biography, something that happens often during these sessions.

To his credit, Bond questioned if there was any origin story to Macca and the instrument. “What did you do, you just started tinkering about on piano?” he asked. McCartney blew him off with a “yeah, sure.” But there was more to it.

“To us kids, [my father] was a pretty good player, he could play a lot of tunes on the piano,” Macca recalled in Barry Miles’ 1997 biography Many Years From Now. “I used to ask him to teach me but he said, ‘No, you must take lessons,’ like all parents do. I ended up teaching myself like he did, by ear.”

Decades later, Paul told a similar story in his own book, 2021’s The Lyrics.

Dad wouldn’t teach me the piano, though; he wanted me to take lessons. He didn’t think he was good enough and, because my parents had aspirations for us, he wanted me to learn the ‘real stuff.’ I took a few lessons from time to time but ended up being pretty much self-taught, just like him. I found lessons to be too restricting and boring. It was much more interesting to make up songs than to practise scales.

Paul indeed received professional lessons, briefly. Here’s his old teacher, Leonard Milne, remembering Paul McCartney the piano student from a 2010 interview in Mark Lewishon’s Tune In:

I gave Paul one lesson a week, at a grand piano I had in the lounge at my parents’ house, 237 Mather Avenue. He started on The Adult Beginner’s Guide To Musical Notation but this didn’t last long because he said he wanted to learn by ‘chord symbols,’ letters printed under the notes — like ‘C7,’ say. It’s a musical shorthand he would have known as a guitar player. He didn’t want to learn the real technique, he wanted to rush ahead — he was clearly a boy with talent who didn’t want to be held back. I also didn’t set homework because Paul made it clear he wanted to press on, not fiddle around with paper.

Fiddle around he did, teaching himself on the piano at home in his teenage years. (Paul had another aborted attempt at formal piano training in the mid-1960s, when he was already established in the Beatles, a brief story he shared in his 2023 A Life In Lyrics podcast.)

Naturally, Paul pressed on in these early moments of the January 14 sessions, playing brief, catchy progressions on the piano. He was the only Beatle there anyway; he had the time to mess around.

“Unless you stop yourself, there’s no stopping yourself,” Macca told Bond – who was visibly beaming throughout the scene in Get Back, in awe and truly engaged at the piano lesson. “Unless you feel like stopping. there’s really nothing to stop you, ‘cause that’s it then. There it all is.”

Paul then launched into “Martha My Dear” – just an 8-week-old album track at this point in time – and added the comment, “See, but then you get to sort of wonder how people do all those contrapuntal things.”

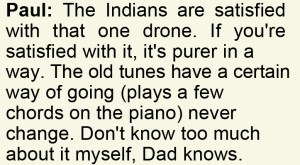

“A lot of old tunes have just a set sort of chord pattern. Because that’s the great thing, once you stop trying to find out chord patterns, you really suss what people are doing and what musicians are doing.”

The decision to play “Martha My Dear” was clearly deliberate on Paul’s part. It wasn’t merely a piano song near the front of his mind. Here’s Paul, decades later, as quoted in Many Years From Now, discussing how he considered the song’s piano part when he wrote it:

When I taught myself piano I liked to see how far I could go, and this started as a piece you’d learn as a piano lesson. It’s quite hard to play, it’s a two-handed thing, like a little set piece. In fact I remember one or two people being surprised that I’d played it because its slightly above my level of competence, really, but I wrote it as that, something a bit more complex for me to play.

In real time, on the Nagras, Paul plays what sounds like a few seconds of “San Francisco Bay Blues” – a song he covered throughout his solo career, including on his 1991 Unplugged appearance. John Lennon fooled around with it, too, during the Imagine sessions in 1971.

In Get Back (which edits it out of order, placing it prior to “Martha”), this 10-second piece is credited to them both as a Lennon/McCartney original retroactively titled “Bonding (Piano Piece).” I’m with the A/B Road bootlegs and others when it comes to credit – this doesn’t sound like Paul conjuring an original improvisation. Especially in the context of his follow-up statement.

“Old tunes, you know, they are just a certain way of going,” Paul told Bond. “And they hardly ever vary from it. I don’t really know it, you know, my dad knows that better than I do.”

The brief and highly unorthodox lesson was over, with Bond going back to work after admitting, “I must get myself a piano.”

We’re not going to pretend that Paul only started becoming adept at piano in 1968 – he was playing it on stage in the Hamburg days. Still, he considered himself a relative neophyte, whether we all believe that or not.

Only a few days earlier, prior to debuting “Another Day” on the Nagras, Paul said, “I better go and put in some piano practice.” True, he may have been trying to get out of a conversation with Michael Lindsay-Hogg, but he said it nonetheless.

For a man who didn’t know how to read music and thought of himself as a novice, teaching the instrument came comfortably. Perhaps it came from his own potential desire to be a teacher, if he wasn’t in a band.

Engaged with literature, a young Paul McCartney “didn’t know if I would actually get to university or get somewhere,” he said in Many Years From Now. “What was my next thing gonna be? Teachers’ training college?”

A brief edit of the conversation appeared in the original Get Back book published with the Let It Be LP in 1970.

Paul said as much to American audiences at the dawn of Beatlemania, too, in a February 11, 1964, interview with WWDC-AM’s Carroll James, one of the DJs credited with being the first to play a Beatles song on American radio.

“At that time, I thought of being a teacher, actually,” Paul said when he was asked what his plans were if he wasn’t a Beatle. “But luckily, I got into this business, because I would have been a very bad teacher.”

Only a few months before the Get Back sessions, Paul told Tonight Show guest host Joe Garagiola and American audiences, “I was nearly going to be a teacher, but that fell through, luckily.”

Still, here he is, January 14, 1969, embracing and excelling as musical instructor. School was on his mind, even if it was in the subconscious. He continued at the piano, this time playing a new song.

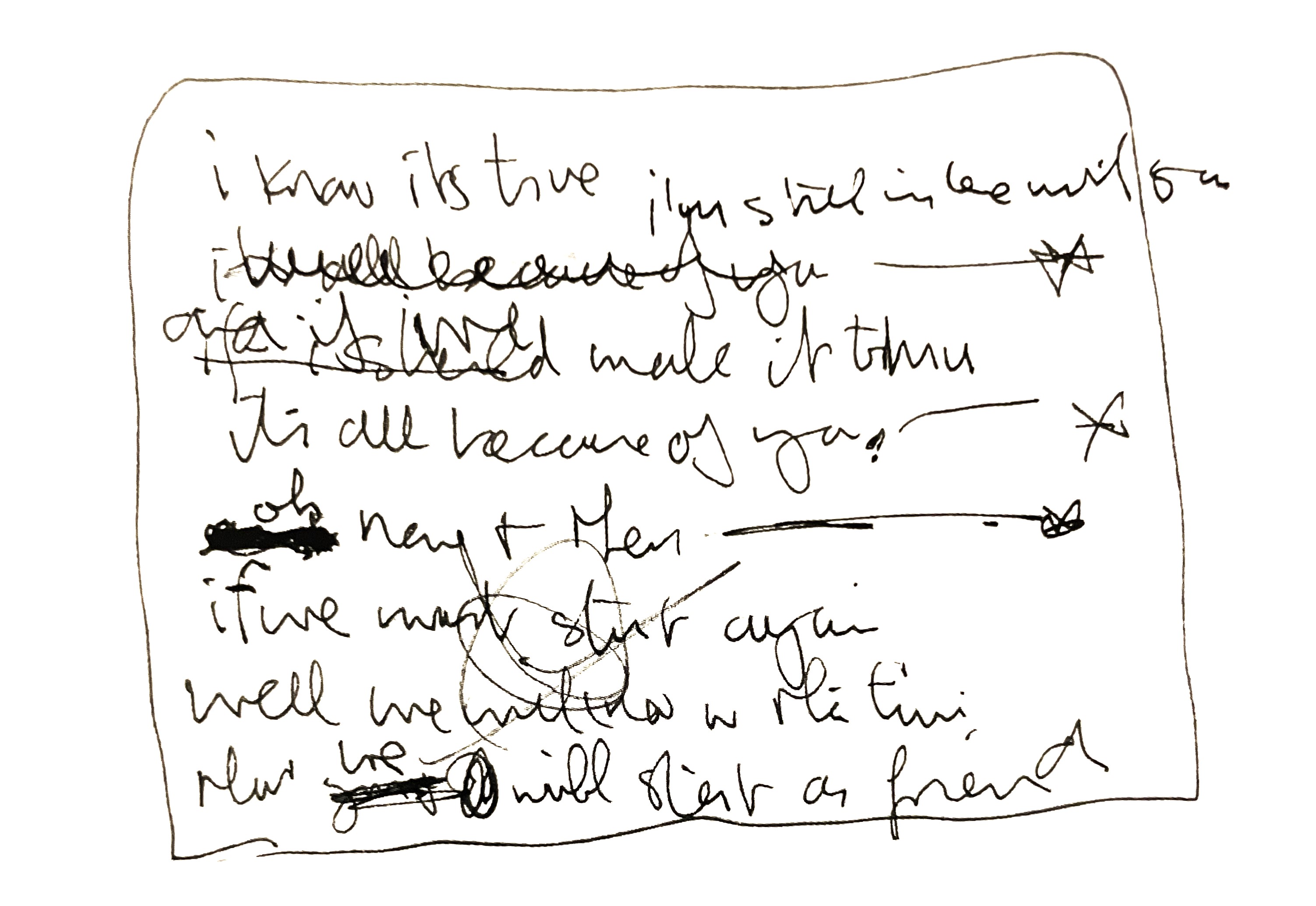

“I had one this morning,” Paul said about five minutes after Bond’s lesson ended. “But it was just like, ‘The Day I Went Back to School’ or something.” The estranged George Harrison presented his “last-night songs” earlier at Twickenham, and so did Paul.

There was only a single verse, repeated several times.

The day I went back to school, the day I went back to school, the day I went back to school

The teacher said, would you like to come back tonight?

I said, no thanks. I’m doing all right without you.

Paul was a long way from 1977’s “Girls School,” and resisting the kind of potentially illegal temptation mentioned in that song’s lyrics isn’t particularly rock and roll of him. But things were weird at this point in Beatles history, so I guess anything goes.

We’d never hear the song we all call “The Day I Went Back to School” again, not during the Get Back sessions nor anytime since.

But the point remains: Teaching and learning was something on the forefront and in the subliminal corners of Paul’s mind on January 14, 1969. Whether it was in private, like at the Grohls’ in 2014, or in the 2021 documentary series “McCartney 3,2,1,” when Paul was demonstrative to host Rick Rubin.

Like Grohl said, Paul can’t stop himself.

Paul Bond’s entire career was ahead of him when he worked on the Get Back sessions, and over the subsequent 40 years, his cinematographer and cameraman credits included “Downton Abbey,” “London’s Burning,” “Inspector Lewis” and all kinds of other things British audiences would know.

Bond also worked on “The South Bank Show,” and that’s where his path crossed with Macca again, in 1984, as part of the small crew working behind the camera.

Bond has also enjoyed a separate act in an a completely unrelated field.

Since at least the mid-1970s, Bond has been a beekeeper. No mere apiarist, Bond is a world champion at the art, earning international recognition in 1979.

Modest in his mastery, Bond credited the bees and the process for his sweet success. Maybe that’s something Paul McCartney taught him when he pointed to the piano for having all the music inside it instead of his own remarkable skill in unlocking that power.

I’ve been waiting all post to write this: Let it Bee.

As Bond said in Idle Beekeeper: The Low-Effort, Natural Way to Raise Bees, published in 2019, when he was asked to share his secret of success: “Oh, I just rinsed out the jars.”

The canteen discussion stands at the core of the day’s drama, but Beatles still made music and did their best to sort out their issues best they could. Dig in here for a better understanding how the day played out:

The canteen discussion stands at the core of the day’s drama, but Beatles still made music and did their best to sort out their issues best they could. Dig in here for a better understanding how the day played out: