It’s spring 2024 A.D., and when we last saw the Beatles, they were vanishing before our eyes in the “Now and Then” video, ascending to Pepperland, probably. In the moment, it was a powerful and tidy conclusion to the clip and the greater arc of their career.

But to paraphrase Paul McCartney, there is no end to what they can do together. Having reclaimed the top spot on the charts in what they trumpeted as their “last song,” the Beatles have chosen to re-audition after all.

The Beatles don’t really do tidy endings. They keep the accidental outtake “Her Majesty” after the majestic “The End.” They break up the band in the most clumsy fashion. And now, after the triumphant back-to-back successes of the Get Back docuseries in 2021 and “Now and Then” last November, the Beatles exhume a movie George Harrison called a “fiasco” and “painful,” John Lennon said made him “sick” and Ringo Starr said had “no joy.” Ringo’s quote is from two weeks ago. Ringo still has issues with Let It Be. Doesn’t he know he’s supposed to promote this thing?

Leave it to me, Ringo. I’m excited, because the return of Let It Be to Beatles canon is critically important, even as it comes off now as the Beatles trying to be completists.

Once I started listening to the full run of Nagra Tapes on my own in 2012, it completely changed my point of view on how the sessions played out. I’ve been writing that story here for 12 years. And for most of that time – until Get Back premiered — I could only cross-reference the Nagras’ account with what amounts to a late 20th century antique (a video cassette of Let It Be) and nearly 50 years’ worth of public grievances. And that’s precisely why I didn’t think the film should have remained inaccessible for so long and truly feared it would stay buried. Because Let It Be didn’t tell the story of the Beatles breakup, the reaction to it did. This, above all else, is why Let It Be matters.

I first saw Let It Be on VHS in the mid-1980s – we rented it and subsequently pirated our own copy in a nod to the tradition of Let It Be/Get Back bootleging. Of course I bought into the idea that Let It Be showed their breakup – I was an impressionable fan, didn’t dig independently into it (where were the counter-narratives back then anyway?) and if the Beatles themselves said that’s the way to interpret the film, who am I to say otherwise? If it’s in Compleat Beatles, it was gospel. Also, remember we didn’t have the full Nagras leaked at the time, only a few hours of bootleg records, mainly of performances.

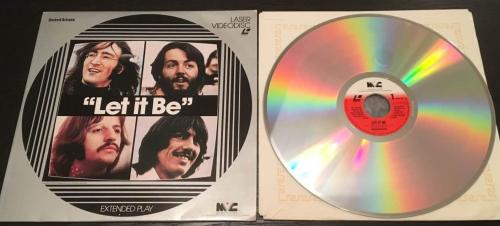

That VHS release, along with an edition on Laserdisc (a contemporary technology with the video cassette) and Betamax, represent the most modern formats on which Let It Be exists prior to its streaming debut. I’ve written this before, but it’s worth repeating: In the time since street-legal Let It Be appeared on store shelves, you could have picked up A Hard Day’s Night on VHS, Betamax, Laserdisc, DVD, Blu-Ray, 4K UHD and streamed it.

The last UK television broadcast of Let It Be came May 8, 1982, according to the Radio Times. The film was screened sporadically in American theaters into the mid-1980s, but then it simply disappeared. Other Beatles productions remained stocked, promoted and upgraded. Magical Mystery Tour (which had its own terrible reputation for a long time) was belatedly released on VHS in October 1988 – like the other Beatle movies, it had its subsequent reissues on modern formats.

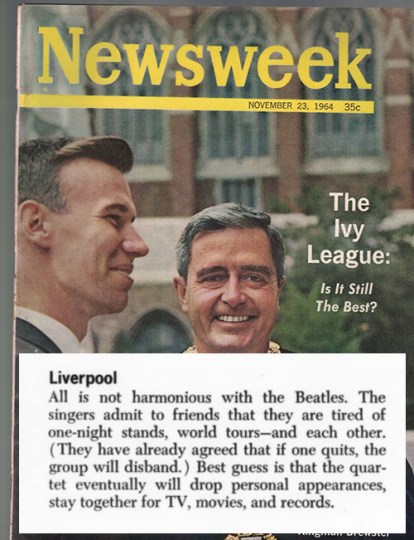

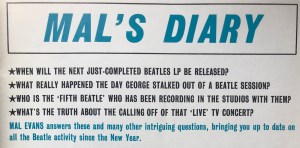

Once in a while, Let It Be’s absence was made conspicuous to the general public.

Buried in a 1991 news story about the future collectible value of Disney VHS tapes (which was really a thing, I remember it!), a mail-order video store reported it was tracking down copies of Let It Be videotapes for $180. For context, you could have bought a decent name-brand VCR for that price – or about 10 new copies of “Star Wars” or “Driving Miss Daisy” (or 13 copies of “Sweatin’ To The Oldies”).

Only three years later, on Anthology Eve, a copy of Let It Be was truly priceless.

“[A]pparently the collectors who own it aren’t willing to part with the title,” said a representative from a different specialty video store in 1994.

That was 30 years ago.

Let it Be is haunted by more than a half century of degradation and denigration as a physical product and a featured work in Beatles history, a ruin by which it’s defined.

If you wanted to watch the movie prior to its Disney+ debut, you were forced to view it on technology that peaked in the 1980s in its native format or on a digital copy ripped from those same 40-year-old analog formats. It’s a bad experience. And even in 1970, the original theatrical release was trashed, including the decision to blow up and crop the original 16mm print to 35mm, and it was hit for poor sound quality too.

(David Bowie deliberately had the Blackstar LP, released days before his death in 2016, physically degrade before your eyes, employing a hard clear plastic sleeve destined to aid in wrecking your record beyond routine wear and tear on the turntable and viewable through a window in the front cover.)

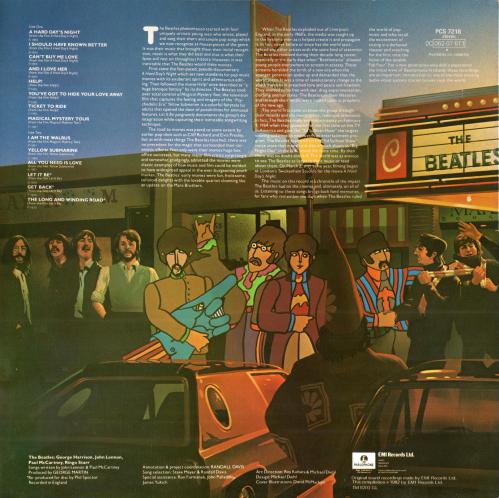

Let It Be on Laserdisc

Before you even slipped your Let It Be Laserdisc (for instance) into your player, you were hit over the head with the breakup story on the back cover:

The Beatles were breaking up. The Beatles were boys becoming men. … One squirms as Paul snips at George and Ringo for not playing their parts correctly, as if the Beatles magic was of a kind that could be whipped into shape. But you can’t blame Paul, because he, like us, saw the Beatles coming to an end.

(Paul said exactly as much during 1990s interviews for Anthology, too: “When we got in there, we showed how the breakup of a group works. We didn’t realize that we were actually sort of breaking up as it was happening.”)

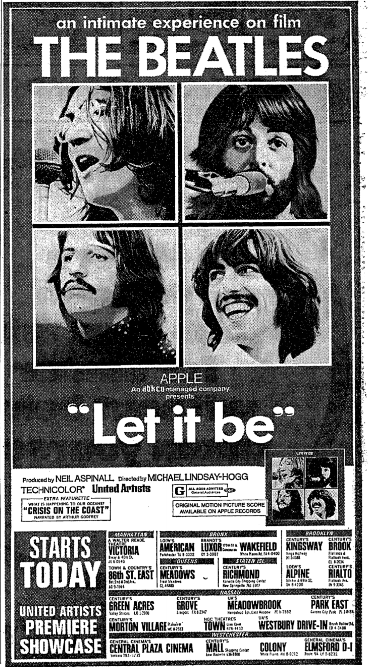

That the film originally reached theaters — a reported 225 in the U.S. alone — a month after the “PAUL IS QUITTING THE BEATLES” headline shattered the music world is critical, but not alone in its importance. Some people still expected the wacky, scripted Beatles to appear on the big screen.

Let It Be followed Help! into theaters by less than five years (to get into that headspace, here are some films that came out in 2019 — it doesn’t feel like too long ago). Magical Mystery Tour, which was considered a misstep in its own time, was shown to British television audiences less than 2 ½ years prior.

Don’t think that matters? To give one example, Variety’s May 20, 1970, review of the film bemoaned “the Beatles’ past togetherness, the chummy camaraderie, the quickness to seize on a line and build a series of gags is no longer there.”

We can nitpick even further and argue that if someone wanted to spend their $1.50 or 6/1 ½, maybe it was better spent on Woodstock, which was in theaters much at the same time (Woodstock was reaching more theaters as Let It Be completely ran out of steam). Running 100 minutes longer than Let It Be, the cinematic release of the concert documentary earned widespread critical and commercial acclaim.

Just a few pages away from the movie listings for Let It Be, reviews and stories touted the Beatles’ recent split, and record store ads promoted Paul’s new solo LP.

Or, as that same Variety review said, “If the film has an air of emptiness and resignation, it is because we know that this is almost certainly the last Beatles picture we are going to see.”

Let’s be clear about the Beatles’ audience, now and then. The younger Beatles fan base that exists today is utterly outstanding, bringing a completely different perspective on the group and, critically, lacking the baggage so many of us had to live with and work to shake free. I’m a second-generation fan, a born in the mid-1970s and too late to be around for Beatles’ first run, but I remember the possibility all four could one day reunite. And I remember hearing on the radio John was killed.

I grew up with The Compleat Beatles, Lennon Remembers, Shout! and later aged with Anthology and Drugs, Divorce and a Slipping Image – so the story was baked in: Let It Be was hell, period.

Even the Beatles’ own records promoted that this was a bad time. The back cover to Reel Music (1982) said “Let It Be poignantly documents the group’s disintegration while capturing their inimitable songwriting technique,” while the liner notes to Let It Be … Naked nearly 20 years later put it this way:

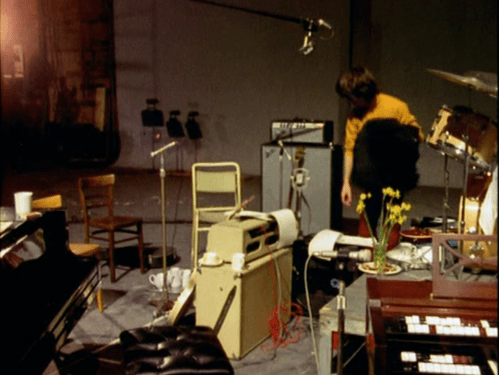

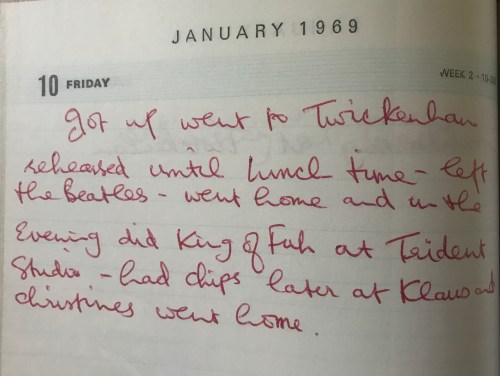

It is the Twickenham sessions that have characterised the whole Let It Be project as an unhappy one both in the minds of the Beatles themselves and anyone who saw the documentary footage in the movie.

In 1970, Get Back was merely the name of a song and an abandoned LP (and film title) while the Nagras sat securely in Apple Records’ vault. Multiple generations loved the Beatles, but they were all “first-generation” fans who witnessed the group’s evolution and dissolution in real time, not forced to read about it in a book or watching it from a documentary. When Let It Be was promoted in theaters, there wasn’t a new generation of fans to reach.

Much as the audience mattered, the four most important figures requiring appropriate contextualization are the Beatles themselves. To them, Let It Be wasn’t just a monthlong session in 1969 and a movie premiering after a breakup in May 1970. The Let It Be experience spanned the 16 months in between too. That’s a long time.

It’s time that included rejected cuts of the film (“Let me put it this way. I’ve had three calls this morning to say [Yoko Ono footage] should come out” is how director Michael Lindsay-Hogg remembered the reaction to an initial screening).

Those 16 months included several rejected Glyn John edits of the soundtrack album, tapes eventually being dumped on Phil Spector and Paul hating much of what Spector did.

It included John saying he wanted a divorce from the Beatles, and later McCartney accepting it, properly beginning the Beatles solo era.

It had all of the Northern Songs drama and the disintegrating Apple. And Allen Klein brooding over everything.

All of that happened to the Beatles as part of their Let It Be-era experience, when a long and lonely “winter of discontent” really spans six calendar seasons. We can separate an 80-minute film from the period, but how could they?

The music wasn’t blackballed the same way the movie was. I always thought it was great, and I never bought John’s complaints about it (“[Phil Spector] was given the shittiest load of badly recorded shit – and with a lousy feeling to it – ever. And he made something out of it … When I heard it, I didn’t puke.”).

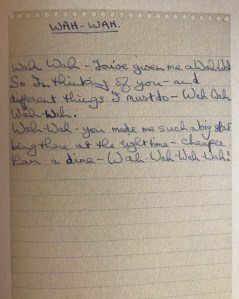

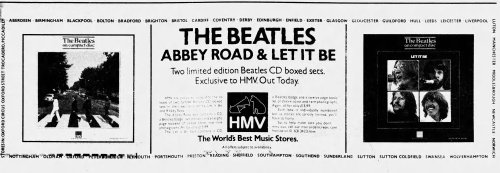

I may not have been in under the lights and in front of the cameras, but I do listen to the music and haven’t puked either. It makes me feel quite good! Let It Be made its CD debut in tandem with Abbey Road to great fanfare in 1987, capping the band’s reissue campaign on the new-ish format. A dozen songs from the sessions appeared on 1996’s Anthology 3. Seven years later in 2003, a reworked mix emerged as Let It Be … Naked. We can even throw in Reel Music and the Movie Medley for more examples that they fully incorporated Let It Be’s music into their catalog since its release.

I think the film just sat there as this giant symbolic target. It was harder to pan the companion soundtrack LP when it was such a smash – it had the biggest initial sale of any LP in American history at $26 million in 2 weeks. The movie, on the other hand, was a relative box office failure, pulling in $1.06 million gross. That sounds like a lot of money until you see A Hard Day’s Night made $11 million and Help! pulled in $12 million.

If the music from the same sessions have been tolerated by Beatles Inc. over the last 50 years, what was so damning about Let It Be’s visuals for so long? Was it the scant minutes featuring Yoko in the frame? The “confrontation” between Paul and George. The waltz? We know it wasn’t about Billy Preston, and the rooftop has long been justifiably lionized. The three completed songs performed in the basement (“Two of Us,” “Let It Be” and “The Long and Winding Road”) are perhaps staged a bit too formally, but those have resurfaced at various times in Beatle releases (eg., two of the three on the 2015 “1” DVD).

There is very little in the way of actual dialogue – as in full, extensive conversations — in Let It Be (and in its original print, which is very muddy compared to the MAL-enhanced sounds of the 2020s).

Much of that dialogue fits on one side of a 45, in fact:

George has been quoted multiple times referring to Yoko’s “freakout” with John in Let It Be – but that never made the final cut. An early edit long colored George’s opinion of the film – it wasn’t a first-hand memory, since he wasn’t in the room when Yoko performed with the others. Did George even see the theatrical version of Let It Be?

It’s probably a matter of simple bias: When you listen to Let It Be you can’t see Paul and George bickering, John asking if they can “play a fast one,” Paul yawning, Ringo looking like he’s going through the motions or Yoko just sitting there.

“I’ll play, you know, whatever you want me to play. Or I won’t play at all, if you don’t want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you, I’ll do it.”

The result is actually backed up by science – what we hear isn’t as sticky as what we see.

Paul and George did bicker. Yoko did just sit there. That’s real, even if that’s not all they did.

What is spread out over eight hours in Get Back simply didn’t translate as well over 80 minutes in Let It Be. Some of that was by choice — maybe it could have benefitted by one less oldies cover and one more evolution of an original song — but there was really little wiggle room in the format.

We’re lucky to have Get Back, for its clarity of picture and sound, and all that footage. Normally a recording session wouldn’t have a particular story to tell — group frustrations come to a boil, a member walks out, but they rally and stage a memorable performance, etc. — and in 1969/70, the Beatles never intended to tell anything more than “this is how an album is made, and here we are performing it as the payoff” as the original TV concept.

And to that end – with Get Back as its companion — Let It Be should be considered an honest depiction of the band. Still, it’s always been a struggle to describe what exactly Let It Be is.

The original movie trailer (which was given an homage in the 2024 Disney+ trailer) asked viewers to view the band “rehearsing, recording, rapping, relaxing, philosophizing, creating.” One movie ad was more blunt: “The Beatles singing their songs, doing their thing.”

Let It Be appeared on HBO in the late 1970s, and the cable network’s guide described the film on different occasions as “A film to make you smile” and, simply, “McCartney sings Besame Mucho.”

The original movie poster (“an intimate bioscopic experience”) and present-day blurb on Disney+ (“Available for the first time in over 50 years, the original 1970 film about the Beatles”) both tout the plain fact that Let It Be is a movie as it’s main descriptor.

It feels like the original VHS box got the story right, with a positive spin not common at the time:

An exhilarating documentary of the making of an album by The Beatles, the film concentrates on the many recording sessions that went into the production of the “Let it Be” album. It offers a unique glimpse into the creative process of this world-renowned group as well as the subtle relationships among the individual members. There is jamming of old songs and painstaking work on new ones. In search of a new direction, The Beatles play an inspired concert on the roof of their London offices.

In the announcement of the 2024 reissue of Let It Be, Peter Jackson said Get Back and Let It Be “enhance each other.”

‘Let It Be’ is the climax of ‘Get Back,’ while ‘Get Back’ provides a vital missing context for ‘Let It Be.’

That first part sounds reversed, but the director is absolutely right. Let It Be isn’t backward compatible because of how it directly influenced the subsequent 50 years of Beatles history. Let It Be owns it’s baggage, period.

Get Back told a specific story, but it was reactionary, too, not simply giving a nod to Let It Be, but deliberately clarifying — and in a sense undermining — some of the original film’s more negative moments.

My favorite example (of several): Paul tries to stifle a yawn in Let It Be, 50-year-old proof that the band is bored. But a drowsy Beatles performance of “I’m So Tired” results in a minute-long sequence in Get Back, with everyone yawning. George yawns his way through Paul’s magical “Get Back” origin story.

For all the drama in Get Back — agonizing over the band’s future, dealing with walkouts (George) and sit-ins (Yoko) — the only real resolution we get was to the problem of how to stage the show, by going onto the roof. Both films feature the same ending, with Get Back criminally dustheaping the full indoor performances, a robbery rectified with Let It Be’s restoration.

No matter how Michael Lindsay-Hogg edited Let It Be, he was stuck in his time. We all knew what came after the credits in 1970 — it wasn’t a gag reel or sneak preview, but a very public breakup, a breakup that was inevitable whether the January 1969 sessions were in front of cameras or not.

“We filmed the whole thing showing all the trauma we go through,” John said in the April 12, 1969, Melody Maker, which hit newsstands right around the time the “Get Back” b/w “Don’t Let Me Down” single was released and more than a year before Let It Be reached theaters.

Tellingly, there’s more to the quote: “Every time we make an album we go through a hellish trip.” (emphasis mine).

Let It Be was put together in the Beatles’ time, yet could only reflect the past tense. It’s no accident Michael put Paul’s piano rendition of “Adagio for Strings” — once voted the ““saddest classical” song — over the opening credits.

Fifty years later, with a different concept and such a different, wider audience, Get Back allowed — and still allows — us to dream on a future. It freed the Beatles from the events that came after it. That story, so focused on the friendship of the band, directly set up “Now and Then.” The same rooftop ending delivered an alternate ending.

The existence of Get Back offers the original Let It Be the same liberation. Today, in 2024 and beyond, it’s indeed the climax to Get Back, the scar that healed over, at once an apocryphal footnote and a window into the post-breakup era — if you know to look for it.