After a proposed overseas concert in a Roman amphitheater in Libya is scuttled by Paul, citing Ringo’s insistence on staying in England, a suggestion is made to perhaps go small and shoot a Beatles concert in a back garden, presumably somewhere in London.

Director Michael Lindsay-Hogg quickly dismisses the idea, suggesting it would end up like a “little promo film … instead of a Beatles television show.”

Sitting in on the discussion, George Martin cuts to the chase and thinks even smaller, proposing “we just do it in the other studio.”

Paul shifts the focus off the venue and back to the composition of the crowd.

Paul: We’re all prepared to do it with an audience. But what Yoko said is right — we can’t just have the same old scene. If it was the same old audience and we were … all naked when they came in, then that’d be a different scene, you know?

MLH: I think she’s totally right about that, that’s one of my big points.

As the discussion goes in circles, someone in the group asks the simple — but very difficult — question: “What can you do that’s new with them?”

Paul: We shouldn’t really try to do anything with the audience because the audience is the audience, and it’s them, and they’ve come in. It’s us that’s doing the show.

Yoko: Because If I were in New York and I watched the “Hey Jude” [promo on TV] … my interpretation would be that those people around them who are sort of climbing up and starting to sing with were just hired people. If I think that, then it’s OK. But if I thought it was a true audience, then I think, ‘Oh, so now people don’t think of The Beatles as too much’ because all the image that everybody in the world has about The Beatles is that once there’s an audience, they’re going to be frantic and pulling their clothes and tearing it away and all that.

OK, then. Not so sure I’m on board with Yoko’s assessment of the state of The Beatles’ popularity at this point, but hey, she’s soon to be married to a member of the band and was actually there in the ’60s, whereas this blogger was yet to be born.

But still. It seems a bit out of reach to me to suggest that just because a Beatles audience wouldn’t be in full-tilt 1964-era Beatlemania, pulling out their hair and screaming over the songs, means the band isn’t as “big” anymore. It’s 1969, not 1964 anymore. The music scene has changed.

But to avoid what Yoko thinks would be an issue, George Harrison says the solution is something The Beatles had done before.

The good thing is that we could completely create another image, reserve the image of your choice. If we could just think of an image we’d like to be and then we make it that one, which could be anything. We could just be a nightclub act, or anything, just the smoochy, low lights and 10 people.

Wheels turning, Lindsay-Hogg says, “Then you’re a little cabaret act,” before he and George Martin agree again that there should be a large audience that’s not necessarily any kind of focal point, just to be used as a sounding board.

But then Paul picks up on George’s idea and gives it a twist.

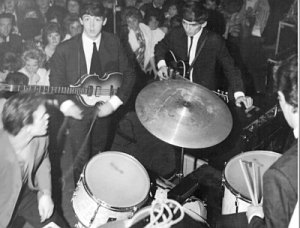

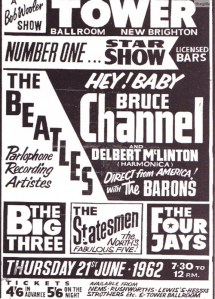

I thought, like, a ballroom. If we did go right back … and did it purely like a dance. “Come to the Tower Ballroom, there’s a dance on. Oh, incidentally, we’ll be the band there.” And we’d go on, play all the numbers and we’d play it like we’d play a dance, without trying to sort of announce anything. There’s a fast one, there’s a slow one, and everyone, like, dances. And there might be a fight or there might be the kinds of things that happened at dances. Or it might be a very sedate, quiet dance.

Presumably, Paul’s referring to the Tower Ballroom of New Brighton — just a ferry ride ‘cross the Mersey from Liverpool — a venue they played numerous times in 1961 and 1962.

I actually sort of love this idea, with the full understanding that it may just take hired hands to get an audience to ignore the fact they’re at a Beatles concert and just go ahead and actually dance.

I actually sort of love this idea, with the full understanding that it may just take hired hands to get an audience to ignore the fact they’re at a Beatles concert and just go ahead and actually dance.

And to do that, as my wife said to me, they’re really just making a long music video. What’s the point?

Lindsay-Hogg is on board — in essence, he says — because he likes its simplicity. But that’s where his agreement ends. “What you’re asking for is a really, really simple approach, which I think is right,” the director says. “But I’m not sure just to have an audience dance around you is good that way. I don’t think you are just a local band.”

Paul, and the rest of the group in the conversation, agree. But after digging deeper into the idea, Lindsay-Hogg ultimately thinks it’s a non-starter.

MLH: The only time on TV it didn’t work for you was when you went on … Top of the Pops, and they did dance, do you remember that? And they didn’t really do very much. And that would look so crazy. It looked crazy for four minutes, but it would look lunatic for longer. It would have been in the bad way, it was so sedate, and you all were so sedate back then.

The essence of this idea is the simplest approach possible. The essence is correct — totally, totally what I believe — but you’re just not the local dance band. Would that you were, but you’re not. So that’s going to be very hard to achieve.

Paul sticks with his newest idea, saying that if they’re going to be artificial and build a set at Twickenham to mirror the Tower Ballroom anyway, why not just go to the Tower itself?

We learn a little bit more about the Let it Be film’s early timeline in Lindsay-Hogg’s response.

MLH: That was one of the reasons we started veering off on these ideas was when we were looking at locations that Friday afternoon after Christmas, and all the locations looked like four steps up from a boutique, you know what I mean? Four years ago everyone was shooting in a boutique, and now it’s a disused sawmill or whatever it is. It just looked like plastic locations.

Everyone agreed it was a phony look, certainly something the group was seeking to avoid.

Also notable here is that the director was scouting locations on Dec. 27, 1968 — a mere 10 days earlier. Good on Lindsay-Hogg, too, for working hard; he directed “Rock & Roll Circus” just 16 days prior.

Yoko won’t give up on the band staging a show before anything remotely like a conventional audience, comparing the scenario to actor Richard Burton, and saying that people don’t want to see him performing on stage before a “fixed” audience.

No matter what kind of audience, it s going to look crummy. What he is is a legend. Seeing him on his own private boat or just seeing him shaving is just more dignified than seeing him perform before a fixed audience. Do you see that point? That’s why it’s better to show you in your private home, or George’s home or something. “Oh, this is much better than a fixed audience.”

Someone, perhaps Mal or Neil, out-Yokos Yoko by suggesting a performance at The Royal Academy or Tate Gallery — “with nobody there but the pictures.” Naturally, she agrees.

Lindsay-Hogg still wants none of that, saying, “Once you get up to perform as The Beatles, you have to perform to someone, even if it’s going to be this different kind of audience.”

The debate churns on.

MLH: Certainly yes, you play straight at home. But I have a feeling that’s not big enough.

Yoko: But that’s big. See the private home of Paul McCartney or George Harrison.

MLH: We could fit that into the documentary.

George Harrison reflects on a “Bridget” documentary (presumably Bardot), describing her taking the audience to St. Tropez as she “sings a tune over her front gate and walking around the pool.”

Insisting that kind of minutia can be incorporated in the documentary, Lindsay-Hogg then offers what turns out to be his concluding argument for the day.

If you just get up to perform, you either have to be performing directly to the people at home or to an audience. It’s only two ways. Maybe it would work for the people at home, I just don’t think there’s quite enough scope. And I think the idea’s good, because we have to think about the audience — because you are so riddled with audience. The audience is so much part of the first half of you musically — [under his breath as an aside] says the critic from the Guardian — the audience is so much part of the mystique.

After a mention of mystique, we’re left with a mystery — the tape cuts off abruptly, and the next track is merely a nondescript improvised instrumental, and there’s no return to the discussion this day again.

And what of the Tower Ballroom? Had The Beatles performed there, it would have been the last hurrah for the venue. It was destroyed by fire just three months after this discussion.