“The world is still spinning and so are we and so are you. When the spinning stops – that’ll be the time to worry. Not before. Until then, The Beatles are alive and well and the Beat goes on, the Beat goes on.”

These were the instructions Apple publicist Derek Taylor articulated April 10, 1970, the marker for the end of the greatest pop music group there ever will be, the day the papers blared “PAUL QUITS THE BEATLES.”

That was more than 53 years ago, and it’s still not time to worry.

I felt compelled to write about “Now and Then,” the Beatles’ new single, and “last song,” even though I generally keep my focus to the Get Back sessions of a half-century earlier. One of the reasons I started researching and writing They May Be Parted in 2012 is because I thought I was investigating the endgame of the Beatles, and I wanted to understand that ending. Listening to the Nagra tapes of the sessions themselves, the January 1969 sessions weren’t what we were led to believe, a revision to history that now is mainstream opinion since the release of the Get Back docuseries.

I’ve posted some takes on “Now and Then” on social media and voiced a few others as a podcast guest, but since I have this permanent platform, I wanted to post here for posterity, too. Maybe this is more for me than anyone else. I tried to keep my thoughts in some kind of order, but this is certainly a brain-dump of high order.

“Now and Then” was released just over a week before I published this post, and today hit No. 1 on the U.K. charts. My feelings on the song and the accompanying video evolved in that short time, and may continue to, I’m sure.

There simply won’t be and can’t be consensus on any aspect of “Now and Then.” Contemporary critics routinely called Beatlemania a fad. One writer famously said Sgt. Pepper was “ultimately fraudulent.” Abbey Road was described by another as “an unmitigated disaster.” So from the jump, we can abandon any thought of a common opinion and there doesn’t need to be. It only matters what it means to you, if anything. It’s like attending a funeral — you go because you feel compelled to mourn for your own personal reasons.

Assuming we all know the original backstory – John Lennon committed the idea to cassette in the late 1970s and widow Yoko Ono handed the tapes of this and three other songs to Paul McCartney in 1994 for use as potential new Beatles songs – let’s pick things up in 2023 with the song’s rollout.

One basic truth to have any “Now and Then” discussion: We simply have to accept the fact this song and video exist in order for us to have a reasonable conversation about it. Whether the song should or shouldn’t exist never was our call. It was up to the two living Beatles and the two estates. In the 1990s, the decision was made to break the seal and reopen the Beatles as an active unit. This is just a continuation of that act in the 1990s.

Is it real, or is it TDK?

George Harrison left explicit instructions to his son, Dhani, and Jeff Lynne outlining how he wanted Brainwashed, his posthumous 2002 LP, to be finished after his death. John didn’t leave behind anything except for the music itself. If the tape of “Now and Then” actually said “For Paul” in John’s writing, we just don’t know if that meant it was dedicated to him, meant to give to him to listen to or something else altogether. It could imply there were tapes that said “For May” or “For Sean.” Maybe there were and no one else has seen them.

Since I’m picking up the story in 2023 via 1995, I’m not really going to get into John’s original intent or inspiration in writing the song, the deeper Lennon-McCartney relationship, the Carl Perkins “My Old Friend” stuff or anything along those lines. There are some terrific voices in the Beatles-sphere who can offer their opinions on that. But ultimately, the most important interpreter is Paul. If we all (myself included) can hyper analyze every word and every note the Beatles play and find deeper meaning, certainly Paul McCartney has the right to decode and determine how a song by his longtime songwriting partner and dear friend spoke to him.

The 2023 rollout window for “Now and Then” was highly compact, and it allowed for knee-jerk takes and then knee-jerk reactions to those initial takes.

Straight away, Paul stumbled into the first step of the rollout in June, saying AI was key to completion of the song. Really, the blame goes to the person who wrote the BBC headline: “Sir Paul McCartney says artificial intelligence has enabled a ‘final’ Beatles song.”

The clumsy description spoiled the promotion of project from the outset, even if the actual use of the the technology wasn’t anything wrong. If he just said “we’re using same gadgets Peter Jackson used to clean up the Get Back tapes” it wouldn’t have put the rollout on the back foot from the start.

Jackson put together the magnificent making-of documentary, unveiled the day before the song’s actual release, on November 1, pulling together unseen home movies of John and Anthology-era footage of George. How remarkable it was to be able to enjoy them both so alive again. Watching Paul singing along to “Now and Then” in the 1990s was extremely moving.

Regardless of whether the musical performances of “Now and Then” in the documentary were a solid sync job or authentic, the sequence made a straight-line link between the ’90s and now, pulling “Now and Then” into the Anthology era as second-act Beatles song and doing everything it could to ensure George was part of this story. Utilizing the Yellow Submarine time travel and timeline was deft, and little easter eggs like using Magic Alex’s sound “technology” was clever and really gave a deep nod and wink to let even the most diehards know, “We’re with you, and this new song can speak to you too.”

It’s entirely anecdotal, from social media, but people started to weep once they heard John Lennon’s voice in isolation. It took me until a few seconds later, when Paul joined him in harmony.

To me, that’s one of the most important and enjoyable features of “Now and Then,” which was officially released on November 2 — Paul owns his “old-man voice,” which he really hasn’t done during his solo career as it’s become more prominent. He’s treating his Beatles work separate from his solo work, which often takes him out of his realistic vocal range. But for this final Beatles track, he leans into that feature of his singing voice as a complement to John, who in his mid-to-late 30s when he recorded “Now and Then” was about 40 years Paul’s junior at his current age. It would have been like John singing with an 81-year-old George Burns in 1977.

I think the strings do a great deal of heavy lifting. Superficially, this is the biggest difference with whatever they would have worked on in the ’90s, when they didn’t employ strings at all on “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love.” I found the arrangement lovely and not overwhelming, evocative enough of “I Am the Walrus” and “Eleanor Rigby” without overwhelming the listener.

I’ll say the same for the harmonies that were sampled from “Because,” “Eleanor Rigby” and “Here, There and Everywhere.” Giles Martin applied them tastefully and subtly enough into the fabric of the song it sounded completely natural.

Ringo was typically fab on the kit, and his added color on vocals were welcome. But it’s too bad surviving guitar parts were mixed low as they were. Much has been said about Paul’s slide solo in tribute to George — it did make you miss George, and it probably would have had a little more flavor and guts to it had he been around.

I do really feel like they were playing together, instead of this cross-generational, cross-dimensional, analog-digital hybrid. It’s all very tidy, under four minutes, not at all ponderous and conscious of overstaying its welcome.

I thought John’s original recording was a little slight — I didn’t love any of the original piano sketches as they were taped, to be completely honest. Certainly they were never meant to be release-ready or anything close to it.

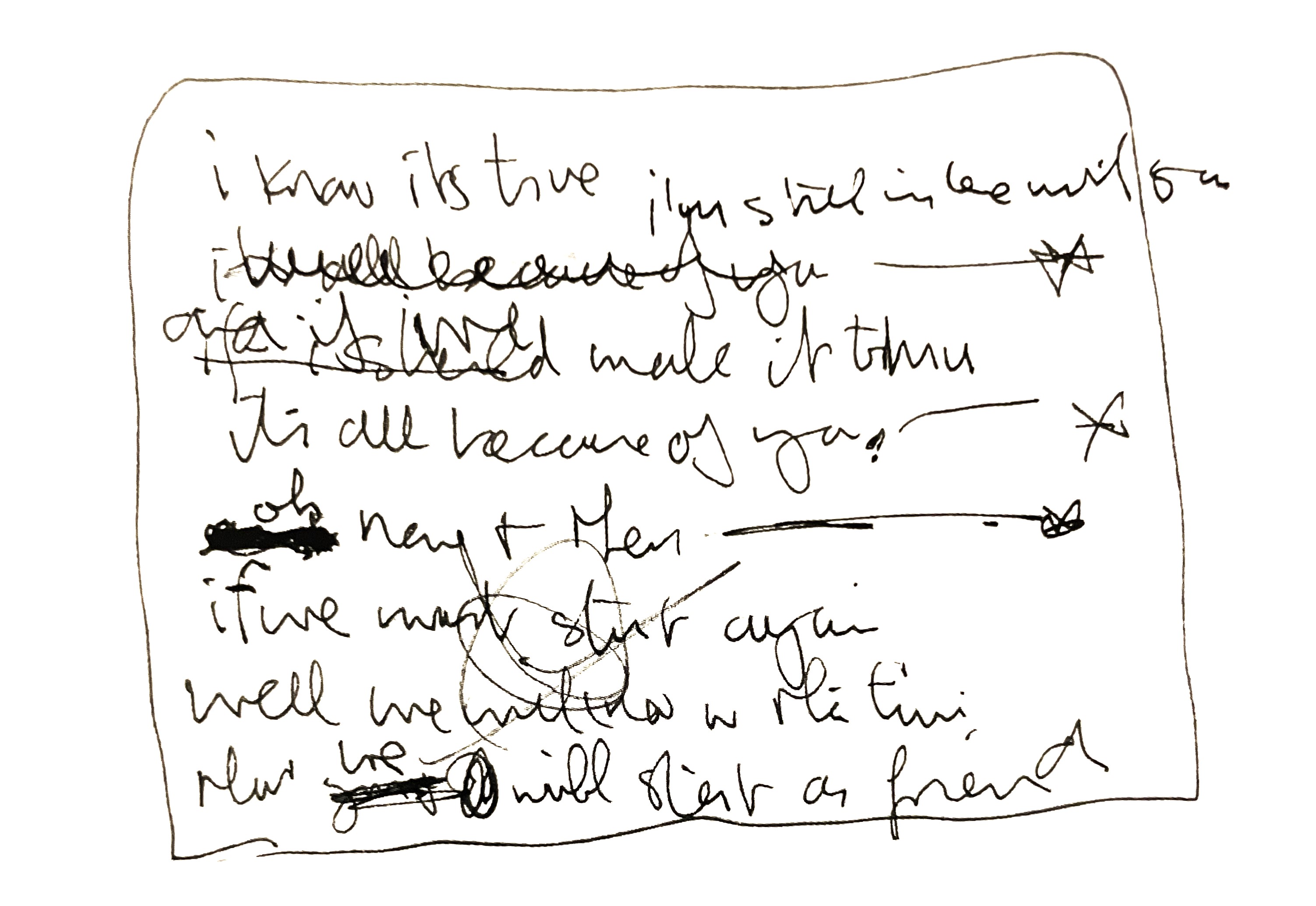

In contemporary interviews from the Anthology era, Paul himself didn’t pull any punches when it came to the quality of the content itself. On what was clearly “Now and Then,” from the November-December issue of Beatlefan:

Yeah, what’s it called – I don’t know, it didn’t really have a title [Sings: “You know/it’s true; it’s up to you…] That beginning bit’s great and then it just goes a bit crummy. We all decided that it’s not one of John’s greatest songs. So that we’d have to manipulate all of that, which is just a little bit more difficult.

I think it’s worth considering how different a 1995 version of the song would have been. We can be assured the overall sound would be different with Jeff Lynne at the helm as originally planned. Would the song have been adjusted, arranged and edited the same way? At the minimum, George would have had a say in the song’s writing and arrangement, probably in a 50-50 manner with Paul (minus some percentage offered to Ringo Starr, to be fair). This is in no way meant to come off crass, but without George’s presence, it freed Paul to fully arrange “Now and Then” with complete freedom.

Even if every now and then he’d feel so insecure, Paul had the confidence to open up the door to collaborate with John as an equal partner, as he felt he had every right to do and had done so many times. If Paul thought the song’s original bridge was clunky, extraneous and “crummy,” he was justified in killing it. I know it seems insane to say “No, we don’t want to hear any more unreleased John Lennon,” but the Beatles were always great editors. Paul McCartney is a magnificent song fixer, and this is the ultimate, final fix.

And this returns me to Get Back. I long heard on the Nagras and everyone has since seen in the series that the others explicitly trusted Paul with their songs. He led the way, whether it was John letting him arrange “Don’t Let Me Down” or George welcoming input to “I Me Mine.” That’s just two small examples in a career of such collaboration.

Does “Now and Then” sound like it belongs on a Beatles LP? Of course not, and why should it? Not quite a mashup, but think of it like the single version of a compilation album. It’s pieces from four of the last six decades woven in under four minutes, I think quite seamlessly. At times “Now and Then” sounds natural in any of those decades, though without fitting comfortably in any of them, either.

What is the essence of a Beatles song? Is it the personnel or the sound? The Beatles didn’t always record as a quartet, certainly not as the years went on. You only needed one Beatle to make Beatles song sometimes. “I Me Mine” was written and rehearsed with no input from John in 1969, and then recorded with him out of the country and having quit the band in 1970. Yet it’s undeniably a Beatles song.

Paul and Ringo got together recently for lunch, but had to send each other files of “Now and Then” — they couldn’t even bother to record the last song in the same room. Maybe there’s something calculated to that: If they couldn’t be in the same room as John and George, then they wouldn’t record without them as a unit. They’d all be apart, together.

The Beatles’ wild variety of styles defines the group’s music. So if it’s not the personnel or sound that makes a Beatles song a “Beatles song,” maybe the essence of a Beatles song rests in its original time — the 1960s. But, as George and John sang in response to “you say stop” in “Hello Goodbye,” they can stay till it’s time to go. And they decided it wasn’t time to go.

In the last 30 years, since the Threetles first attempted “Now and Then,” we lost George Harrison, Linda McCartney, George Martin, Neil Aspinall, Geoff Emerick and so many others, people close to the Beatles, their story and their music. John wasn’t the only one missing anymore, and each of these people to some degree must have been on Paul’s mind as he worked on “Now and Then,” this song of memories and loss.

And to that end, it’s also quite clearly a song of closure. The promotion — so actively screaming that it’s the “last” Beatles song — leans completely into that. But the music does too. I’m not any kind music theorist, but I have two operational ears, and this is what I hear:

- Abbey Road, the final recorded Beatles album, ends with a note hanging, the final note of “Her Majesty.”

- The first reunion single, “Free As a Bird,” has a false ending, and then George’s ukulele coda.

- The second reunion single, “Real Love,” fades out.

- “Now and Then” resolves itself beautifully.

“Now and Then” is the only one with a conclusive ending.

I love the concept of the butterfly effect, so let’s apply it here. There’s no answer, but what if “Free as a Bird” had the poor demo tape recording and “Now and Then” ended up salvageable in 1995? Maybe the quote I shared earlier, where Paul said it was “not one of John’s greatest songs” would have meant “Real Love” would have been the lone reunion song? We’re left to guess.

And that brings us to the video. It’s divisive and a little insane.

There’s a lot to unpack. My initial reaction was that it was too contrived, too scattered. The 1990s Anthology outtakes were outstanding, as it was in the making-of film — images of George we hadn’t seen before and the Threetles at work. But my overall first impression was that this video was the kitchen sink, trying to stuff so much in four minutes: present-day performances, ’90s video, archival footage and photos.

I would imagine that if they didn’t do the “Free as a Bird” video already, that would have been an apt solution.

That’s one way to go, when there’s a member of the band who’s not around anymore, a creative film that had few images of the Beatles as they had been and none of the surviving members pictured in the ’90s. “Real Love” took a more straightforward approach, compiling moments from throughout their career with 1990s footage. But there’s no narrative.

Roy Orbison died shortly after the first Traveling Wilburys album came out in 1988, and in the “End of the Line” video, released a few months later, he was represented by a rocking chair with a guitar and a photograph shown during his vocal lines. It was moving and sad, but I don’t think it was an approach that would have worked for the Beatles, with half the band gone. It would have come off maudlin, and completely against the idea that “Now and Then” was a full-group effort. (Mind you, I don’t think “End of the Line” was maudlin — it was still in the early phases of mourning Orbison.)

I was completely skeptical when I first saw 1967-era “Hello, Goodbye” John and George intermingling with 2023 Paul and Ringo. The word “cringe” was thrown around a lot on social media, and I get that. My thinking on the video quickly evolved from the first to second viewing — your milage may vary.

We’re faced with two issues: Would the departed Beatles want to be represented this way? And if so, should it be as silly as presented?

Let’s not pretend George and John didn’t revisit their Fab Four period in their solo years. Putting aside the many callouts in songs, either cryptic or overt, George did things like dress in the same Sgt. Pepper costume he wore in “Now and Then” and elsewhere, and John literally had the Beatles on the cover of a solo record. Complicated feelings they may have been, they never wrote off that time.

St. Pepper George in the 1974 “Ding Dong” video, one of many Beatle guises he employed as he tried to “ring out the old.”

In their day, the Beatles embraced comedy in their films and promos, and beyond into the solo years (George was the funniest of all, with his estate keeping that flame alive). Even with a wistful lyric at play, it wouldn’t be the Beatles’ way to match it with a bleak visual.

One way they could have gone would have been to make multiple videos, something the Beatles did themselves over their career and when they went solo. Build out a full video of the ’90s sessions co-mingled with appropriate ’70s Lennon home or studio footage. The Beatles at work on their last song.

Another direction would be a more direct clip/highlight reel, something they added to the video for “Real Love,” but now with another 30 years of memories added, and earlier footage cleaned up.

Finally in the last video, they could have really owned the time-travel element and gone completely bananas. Stick Paul into the “How Do You Sleep” sessions. Put 60 years of Ringos into one room. Get the 1980 Paul pretending to be the 1960s Paul and put him on stage with the Plastic Ono Band in Toronto. You get the idea. Really play into the fact these four guys were always together, even when we can document they weren’t.

Those were my knee-jerk impressions of the video, kind of a mixed bag. Then I watched the video again, this time with my wife, who helped me open my eyes to a better interpretation.

A lot of people really don’t like the video, and I get it. It’s jarring, uncomfortable and the technology — as impressive as it is — still isn’t perfect.

Peter Jackson described the concept as “Ringo and Paul in 2023 trying to work on a song and they get invaded by the 1967 Beatles,” but I think there’s much more to it than that.

It’s Ringo and Paul deliberately surrounding themselves with the John and George they knew so well. At a funeral, wake, shiva – this is when we remember and talk of the vibrant life of the person we’re remembering, sharp and in color, not memories of their weakness or death. These days are filled with silly memories and pictures from all across their lives, laughter among the tears. I don’t think there’s any doubt Paul and Ringo vividly remembered a vitalized John and George — and even their own former vigorous selves — when they were in the studio last year working on “Now and Then.” It’s just the Beatles and their closest associates: George Martin was embodied through his son, and Mal Evans through the MAL technology used to extract John’s voice.

This part of the video isn’t meant for us, it’s for them. We just get to be voyeurs.

As the video nears the end, their life literally flashes before their eyes. Again, the animation is awkward in spots, but I’ll argue in favor of the concept. When I look at a photo of people I’ve lost in my life, their memory isn’t stuck in that 4×6 print. They live, they move. Every time I see their face, it reminds me of the places we used to go, a concept Ringo and George certainly understood.

And then we were snapped back into reality, the reality of 1964, and the Beatles all together in a single time and place. With their concluding bow, taken from their performance of “She Loves You” in the “A Hard Day’s Night” film, the Beatles vanish before our eyes, and the lights spelling out their name burn out. That was the point in the video I lost it.

If the rest of the video was for the surviving Beatles, this ending was for us, the Beatles fan, the rest of the world. They were singing to us now, not each other.

Deliberate or not, this ending evokes a dramatic sequence in The Compleat Beatles, an unauthorized but highly valuable biography of the band from 1982. In the sequence on the breakup of the band, we see the iconic black-and-white photos of the band from April 1969, with George, Ringo, John and Paul vanishing, in sequence, as “I’m So Tired” plays in the background, the aggressive lyric, “I’d give you everything I’ve got for a little peace of mind.”

In the “Now and Then” video, that tone has changed. Go to the source in “A Hard Day’s Night,” and you can hear the valedictory statement they give prior to their bow: “With a love like that, you know you should be glad.” See, it does work both ways: If Paul McCartney and Peter Jackson can search for deep meaning in these kinds of things, so can I.

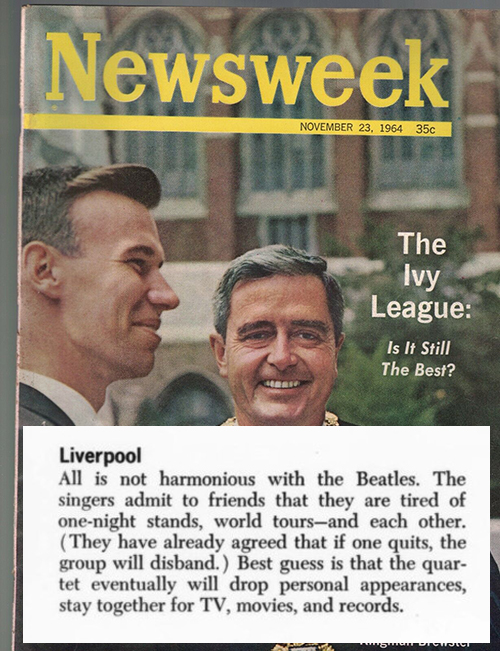

The Beatles have said “Hello, Goodbye” many times. Breakup rumors started in 1964, and continued until they actually broke up. Until their partial reunions. The only endings that ultimately matter are John Lennon’s death in 1980 and George Harrison’s in 2001.

I’ll bring things back one more time to Get Back, Let It Be and original breakup, with these points: No living Beatles (out of four) approved the Get Back edit by Glyn Johns in 1969 (it later came out packaged with the Let It Be reissue in 2021). That’s two fewer Beatles that approved “Now and Then.”

I don’t think they could have sold “Now and Then” as a genuine cosmic reunion of friends, not merely co-workers, without the Get Back docuseries coming first. That set the stage to a mainstream audience that the the Winter of Discontent was much milder than forecast.

And thus ends the Beatles’ final act. Or does it? Paul offered this relevant remark to his fan club magazine, Club Sandwich, in the Winter 1995 issue, when asked if Anthology was the “last word” on the group:

I don’t know. That’s the difficult thing. In the electronic press kit we all enigmatically said, “Where does the circle end and where does it begin? An end is a beginning, of sorts.” But to me, for now, it’s an end.

An entire new generation of fans had the experience of hearing the “last” new Beatles song as their first new Beatles song, something some of us got to experience in the 1990s, in the 1980s, in the 1970s and all the time in the 1960s. Where does the circle end and where does it begin?

There is no end to the Beatles, as long as they occupy our lives, our ears, our eyes. Don’t take it from me. Just ask Derek Taylor, who said this on April 10, 1970:

“The Beatles have changed so many lives, that the need for them still exists. The hope that they represent still exists. And as long as that exists, then they have to exist. They’ve got to be there to fulfill that need, and who are they to take themselves away, to say ‘OK kids, that’s it’? …

“If the Beatles don’t exist, you don’t exist.”