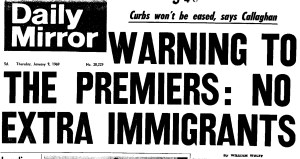

Paul McCartney emerged January 13, 1969, as a journalist investigating a story of his own creation, and he spent the back end of his day at Twickenham Film Studios enduring some newsroom drama to sweat a co-byline with John Lennon and attack most of the five W’s of a catchy little tune the world eventually knew as “Get Back.”

True reporters, they worked on a tight deadline.

“OK, let’s try to get words to ‘Pakistani,’” Paul said of the song, which was very much in progress and still politically tinged. “We’ll do an hour,” telling director Michael Lindsay-Hogg “don’t worry,” because the staff will deliver content this afternoon (even if it didn’t last quite as long as promised).

The Beatles didn’t have George Harrison, who fled to Liverpool, but they still had an imminent live show on the schedule and songs to complete. The enduring yet unsettled Lennon-McCartney partnership amounted as the lede of the secretly recorded lunchroom conversation only recently concluded — as well as the lengthy period Paul spent with others before John’s arrival that day — so this songwriting sprint served as a much needed playdate, too.

But before attacking “Get Back” on the Nagra tapes, Paul continued to share what he felt his approach toward George should be right now, as he spoke presumably, to John and Ringo Starr and with the same candor everyone shared in the lunchroom earlier.

‘Look, I once thought the situation was that, and I don’t anymore.’

But I find that the most difficult thing ever to say. Because I hear myself say it, and I haven’t quite said it. I didn’t quite convince him. And as I think that, you think that, he thinks that — blah, blah, blah, it goes on forever.

Paul continued in another instance that’s unclear who he’s addressing, either straight to John or indirectly to George.

We’ve got the same problem that causes you to get on your guitar and wail. It’s the same one over and over. I’m wailing with ya. But I don’t say it right there and then, because I suspect we mightn’t be wailing about the same thing. So I won’t quite say it, and I never have quite said it, but some time I hope to say it. I may never say it, and fuck it if I don’t.

If Paul was speaking to John, he still wasn’t quite saying it. If it was directed to George, it remained theoretical — George was in Merseyside, as Ringo reported.

Mal sticks around, with pencil

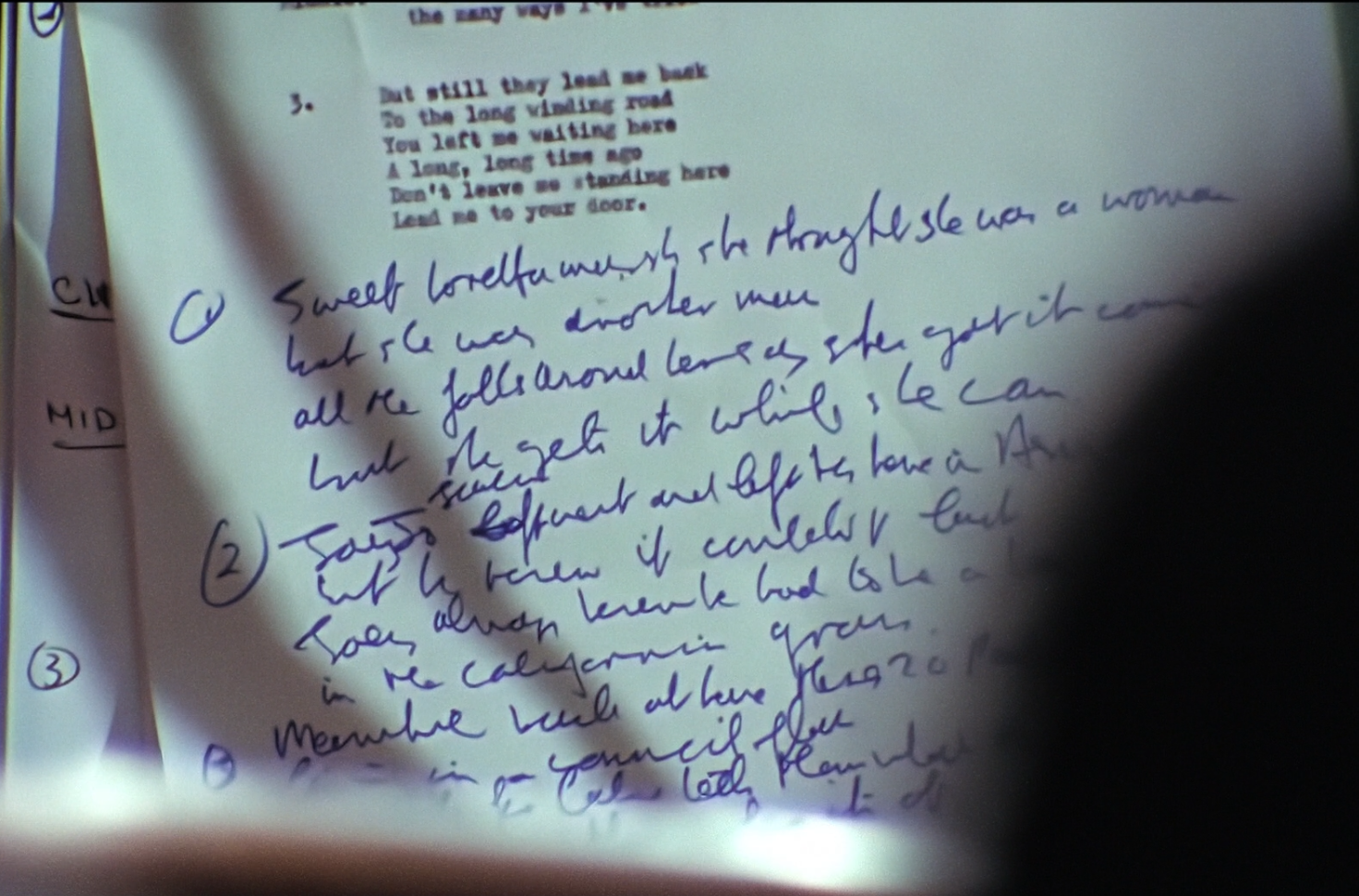

This was a half-hour on the tapes resembling something closer to a vintage McCartney-Lennon writing session. Mal Evans — who Paul implored to “stick around with pencil” — took dictation and, as he did so many times over the past decade (including these sessions), participated uncredited in the songwriting process, too.

Jo Jo Jackson eventually lost his surname, though it stuck for now. Loretta kept her saccharine sobriquet, but her family name was very much up for debate on the 13th, with Paul souring on John’s suggestion: “Marsh.”

“We’re not sure about that, but put it in,” Paul told Mal early in the sequence, though he would quickly revisit that decision. We get to see this next bit in Get Back in an edited fashion.

Paul’s first choice suggests a tapping into the character-rich McCartneyverse.

“Sweet Loretta Mary. it’s got to be a name.” Paul tries out the name a few times, but Mary found her way in only one song from these sessions.

The process continued.

John: Sweet Loretta Marvin.

Paul: It’s got to be a meah [sound]

John: Meatball

Paul: Martin

In other words, “Sweet Loretta Meatball” enjoyed a non-zero chance of being a Lennon-McCartney lyric.

Sweet Loretta Martin was already an option Paul suggested days earlier.

While the surname search continued, it’s notable the established first names — Jo Jo and Sweet Loretta — never encountered debate.

Decades later, Paul maintained Jo Jo had no specific inspiration. From Barry Miles’ 1997 authorized biography Many Years From Now:

Many people have since claimed to be the Jo Jo and they’re not, let me put that straight! I had no particular person in mind, again it was a fictional character, half man, half woman, all very ambiguous. I often left things ambiguous, I like doing that in my songs.

Paul’s 2022 memoir Lyrics reveals no additional information on the people named in the song.

Upon his suicide in 2000, Joseph Melville See, Linda Eastman’s first husband — whom she met and later married in Tucson, Ariz., in 1962 — was commonly referred to as the inspiration of “Jo Jo.” There’s not much to go on beside the name Jo(seph) and the locale — his biography doesn’t otherwise fit the lyric. Moreover, he commonly went by “Mel.” So it’s a nice idea, but he doesn’t seem to be the answer.

(If Paul sincerely wasn’t writing about his future wife’s ex-husband here, that changed in a couple years. Paul openly claimed “Dear Boy” off 1971’s RAM was about See — and not Lennon, as is commonly suspected.)

Paul conceded to the other Beatles less than 100 hours earlier that ”Get Back” was “not about anything,” so it’s fair to take him at his contemporary word. “Sweet Loretta” doesn’t seem to refer to anyone either. He used “Theresa” in place of “Loretta” at one point as he first started working through the song the previous week. As Paul put it about another lyric earlier on January 13, “It sings all right.”

That same singability informed the where of Get Back, too.

Since the song’s origin, the character in the first verse escaped the same southwestern state, Arizona. On January 9, as that verse developed, Paul sang on a few occasions “I left my home in Arizona.” Subsequently, including on January 13, he toggled between “Northern Arizona” and “Tucson, Arizona” as the point of departure. (Tucson is on the southern end of the state, for those unfamiliar.)

After one of the run-throughs, John fact-checked the lyric.

John: Is Tucson in Arizona?

Paul: It’s where they make “[The] High Chaparral.”

The American Western was a fixture on BBC-2, broadcast Monday nights, so it made for an obvious benchmark. More relevant to Paul, the second-largest city in the state was the former home of his girlfriend, who studied art history at the main Tucson campus of University of Arizona. Linda’s first child, Heather, was born in Tucson in 1962.

(Paul’s affiliation with that area was only just beginning: A decade after these sessions, the McCartneys purchased a ranch in Tucson.)

Just across Arizona’s western border lies the Golden State, and the line “California grass” predated most of the lyrics in “Get Back” as Paul sang it at the song’s origin on January 7. But the California reference wasn’t finalized, and this led them to work on the what and why of the lyric.

“Joey ran away from his home in Arizona,” Mal said, searching for a line.

Paul: Looking for a … something to last? … Looking for a what? What is it? Looking for a home to last …

Mal: Looking for a love to last?

Paul: Something like that, yeah.

Ringo played the long game, approaching the title of his 1975 greatest hits compilation with “blast from the past.” (This scene, editied, was featured prominently in the official trailer for Get Back.)

Mal jumped off the suggestion and proposed both “looking for his blasted past” and “trying to escape his past.”

At the end of the day, Paul ultimately settled on “looking for the greener grass,” which comes off a little boilerplate and lazy, especially when he already had the more evocative “California grass” lyric in his back pocket for the time being. Paul was sure to this point, however, that he “had to be a loner,” with that lyric, also dated to January 7, remaining in the song today.

Upon the conclusion of the session, Paul settled on the first verse as such:

Jo Jo left his home in Tucson, Arizona, looking for the greener grass

Joey said you had to be a loner, but he knew it couldn’t last

“Leave that verse, exactly as it is,” he told Mal. “And next time it might be better.”

Throughout this 30-minute sprint working on “Get Back”, the power trio thrashed at full throttle. Like their jams following George’s walkout the previous Friday, they’re edgy and loose. Paul and John often share lead vocals, singing in unison.

With the Beatles’ lead guitarist 200 miles northwest, Paul appointed John for a spontaneous solo. He replied with something rudimentary, but the assignment stuck — the solo remained John’s own through the song’s final performance on the roof.

Even with the song unfinished in so many parts and rushing through a brief window this afternoon, Paul remained characteristically mercurial, criticizing Ringo’s drum outro (“you’re doing a bit too long on those breaks”), vocalizing exactly how he wanted it to sound and offering specific instructions.

“So once you go on to the top tom-tom it’s like four from there on,” instructed Paul.

For a band highly conscious of poor focus and squandered studio time — a week earlier, Paul complained, “I think we do waste, physically, waste a lot of time, the four of us together” — this concentrated “Get Back” session was a very efficient use of time. Whether it was because there was one less cook in the lunchroom or a general understanding the three of them had their own reasons to wail, this particular afternoon was not squandered.

Satisfied with their progress, Paul called it a wrap.

“OK, and we’ll go home now,” he said. “We’ll come in tomorrow and try to do a bit more.” They settled on an 11 a.m.-ish Tuesday reunion in the studio.

But was that aspirational? After all, citing the Twickenham facilities crew, Michael said Apple Films head Denis O’Dell “canceled all his stuff for the show.” That decision, made off screen, set off an obvious chain reaction.

Paul: The [show scheduled for January] 18th should be canceled. So we have to be flexible, we’re going to have to be very flexible now. The 18th today has changed to the 19th, cause we lost a day today. Tomorrow it will change to the 20th. The day after it’ll change to the 21st. If George comes back, put it back a full week.

MLH: I think to stay flexible is important.

John stuck an optimistic tone to close out the day in another sequence captured in Get Back. “I’m leaving my favorite guitar here as a sign,” he promised. Paul meanwhile brandished his Hofner bass, replete with the setlist from their final show.

As Paul read song names for the cameras, nobody was certain if that artifact would remain the setlist from the Beatles final live performance. A token from John may not be good enough, and the other Beatles didn’t have time to hang a sign on George.

The new Beatles show would now be pushed to about two weeks out from January 13. While the songs were gradually taking shape, it was a concert that still lacked form otherwise. But even as the producer was canceling “all his stuff,” Michael said in the closing moments of the day’s tapes, “I think at some point we need to talk conceptually about the show.“

With the future fuzzy and Michael clearly feeling the pressure, Paul played for the cameras.

“So I’d like to say to the cast of this whole production, good night, and thank you very much for having us, it’s been wonderful working with you. ‘Cause I know it’s been wonderful working with me, but it’s been wonderful working with you too.”

“Do you think this will help my movie career or not?” Michael asked.

“You know you need this kind of traumatic event,” Paul replied.

***

The Beatles lost a day, but January 13, 1969, wasn’t a lost day. A Beatles ‘69 Comeback Special clearly required George’s participation — otherwise, why put the show off any longer? — but the other Beatles proved they could at least cover the gaps, produce and adapt in his absence. The attention to the lyrics, John’s guitar solo assignment, the care paid to the music are all proof.

Paul’s Monday was exhausting and cathartic. As the workday began, he described the failure to lure George back into the band, detailed the difficulties of his songwriting partnership with John and shared a vision for the breakup of the Beatles. In the lunchroom, the band’s interpersonal relationships were laid more bare in a presumed private setting. And the day at the office ended with a concentrated, successful songwriting session.

The Beatles — minus George and plus Mal and Yoko — at work on January 13. (Photo by Ethan Russell)

John’s day played out differently. We can sketch a scenario in which he probably slept in and deliberately left the phone off the hook — this was when “telephone’s engaged” prior to the “and then there were two” moment — before dragging himself with Yoko to Twickenham in time for the lunchroom discussion. It wouldn’t be any sort of revelation to say drugs may have been involved in his day. In front of the cameras, in the visual we see in 2021’s Get Back, John didn’t look like he was entirely there. But, there he was.