Mid-afternoon on January 8, 1969, at Twickenham Film Studios, Paul McCartney sat at a piano and microphone and ran though “Let It Be.” Nine months later, and 3,500 miles to the west of London, the Queen of Soul was doing the very same thing.

By that point — October 1969 — Abbey Road was in stores while “Let It Be,” along with the rest of the songs slated for the Get Back LP that would ultimately evolve into the Let It Be LP, remained on the shelf. Aretha Franklin had a copy of the unreleased track, though, and we know she had been promised that song for a long time, going back at least as far as the start of the new year. But she wasn’t getting an exclusive.

Let’s go back to Twickenham, January 8, 1969:

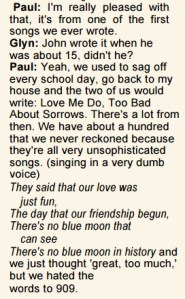

George: You going to give it to Aretha Franklin?

Paul: I’m going to do it, and give it to her.

Specifically, Paul planned to have the Beatles cut a “rough demo from the first rehearsal” once the song was complete and would “try to get her to do it as a single.” But “Let It Be” was not quite complete yet on this, the fifth day of the sessions. The melody is locked down, but Paul only presented the first verse and chorus to this point.

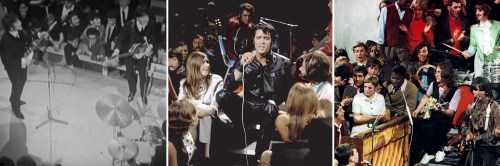

Weight and see: Aretha Franklin does her thing, while Duane Allman (right) does his on a cover of The Band’s “The Weight” on January 9, 1969.

Still, he knew what he had, and its potential as a cover. “It would be great for Aretha Franklin, that number,” Paul said before singing a line in an absolutely terrible imitation of her. (For the record, that same January 8, 1969, Aretha was recording her version of “The Weight” by The Band, whose influence weighed heavily on the Beatles these sessions.)

Ringo provided upbeat drum accompaniment — exactly as laid out by Paul, with a faster tempo than would ultimately surface on the record, and with several awkwardly inserted fills.

Tongue firmly in cheek, John soon offered a lyrical tweak and a poke at Paul’s pseudo-religious lyric, suggesting “Brother Malcolm” as a nod to the group’s do-it-all assistant. (Paul will deliver that line in a few future takes.)

The group would return to the day’s on-again, off-again writing-cum-rehearsal session for “I Me Mine” followed by “The Long and Winding Road,” which like “Let It Be” was similarly unfinished lyrically and being given its first introduction on the tapes to the full band this afternoon.

These repeated truncated takes of “The Long and Winding Road” — which lasted nearly a half hour, split into two separate stagings late in the day — mainly served, as far as the Nagra reels were concerned, as background music for an increasingly captivating conversation about the eventual live show. More about that in the next post.

“The Long and Winding Road” caught George’s fancy, and he called the song “lovely.” Before the end of the day, Paul taught George the song’s chords. Likewise, Paul sketched out how to play “Let It Be,” which was played for about 10 minutes at the very end of the day’s musical portion, and George and Ringo were full participants. The song was never to be played live in front of an audience by the Beatles, but at this point it was clearly in line for the upcoming concert, and Paul sought out additional accompaniment come showtime.

“It’s sort of gonna do like a hymn. That’s why I was thinking we could get audience participation on that,” he told George.

The sleeve for the French release of Aretha’s version of “Let It Be.”

The January 8 session was really the formal coming-out party for “Let It Be,” marking first time Paul played it to the rest of the band these sessions (on tape, at least, but it seems clear if it had been played prior, it wasn’t as extensive).

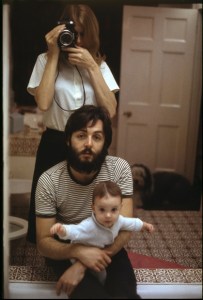

Like “Yesterday,” the song was famously sourced from a dream, but this time around it was the lyrics that were nocturnally inspired.

Here’s Paul, as quoted in Barry Miles’ Many Years From Now:

In the dream she said, “It’ll be all right.” I’m not sure if she used the words “Let it be” but that was the gist of her advice, it was “Don’t worry too much, it will turn out okay.” It was such a sweet dream I woke up thinking, Oh, it was really great to visit with her again. I felt very blessed to have that dream. So that got me writing the song “Let It Be.” I literally started off “Mother Mary,” which was her name, “When I find myself in times of trouble,” which I certainly found myself in.

But to be clear, the trouble wasn’t dated to January 1969. Rather, like “The Long and Winding Road,” “Let It Be” materialized in 1968 amid the lengthy and tumultuous White Album sessions. The two gospel-flavored songs had another link, and that was they were written with other people in mind from the start, too: “The Long and Winding Road” was influenced by Ray Charles.

As for Ray’s future Blues Brother co-star, Aretha never did end up releasing “Let It Be” as a single in the U.S. or U.K., but it was among the standout tracks (her covers of “Elanor Rigby” and “The Weight” were among others) on her This Girl is in Love With You LP, which was released January 15, 1970 — two months before the Beatles’own version came out as a single, and 11 days after the last Beatles recording session.