When we left the Fab Four in the previous post, the band was continuing the wrestle with the bridge in “Don’t Let Me Down.” To Paul, the section “needs things to happen.”

So he proceeds to ask Ringo for a little bit of stop-and-start drumming, some cymbal play and otherwise suggest ways to demolish the pacing of the song.

John seems to like it, or at least not dislike it. There’s a sparseness to it, and maybe I’m nuts, but I almost feel a little Plastic Ono Band thing happening here (“Hold On” maybe?).

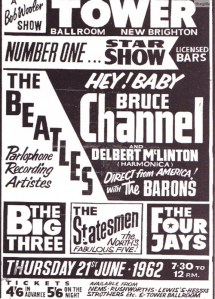

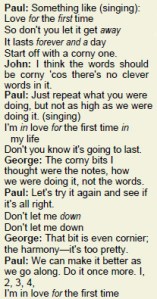

Excerpt from the Let it Be book

One thing that’s enjoyable to listen to as they work on this is hearing the isolations — Paul’s bass, George’s guitar. Meanwhile, Ringo’s a robot throughout the rehearsals. He literally doesn’t say a word (that you can hear on the tapes, at least), soaks up Paul’s instructions and basically steps in to lay down the same steady beat each of the 2,549 (approx.) times they try to tackle the bridge this day.

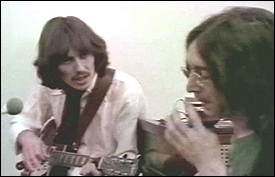

Meanwhile, the tapes cut in and out for an undetermined amount of takes, but it couldn’t have been too long, since they’re still wrestling with the same stuff. Now they’re paying a bit more attention to the instrumentation on the bridge over the vocals. Paul’s looking for more from George in the way of a lead guitar line — overall, not just in the bridge. Soon, John tells George, “We’ve got to keep fiddling around with this bit, so you want a guitar bit. … There’s a point where we’ll to have to concentrate on the guitar for each song.”

But maybe it won’t be now. John gives the band a chance to opt out of the “Don’t Let Me Down” after nearly an hour of not exactly getting very far. “Should we do something else ,then?”

Feel like letting go? Not Paul. “Stick with it,” he replies.

So they continue and struggle with the song’s pace, first going too fast, then overcompensating by going too slow. Things just aren’t getting anywhere. George complains they don’t even know what they’re singing during the bridge — and they don’t. Tape glitches lose some time, but it doesn’t matter. When we’re back, the rehearsals are in the same state. John doesn’t bother singing the lead vocals straight every time — and there’s no point, it’s the same vocals he uses on the final take.

For a moment, they ditch the response vocals and go with simple “aahs” over the bridge, and it didn’t sound too bad. But still a bit superfluous.

So Paul shares what’s on his mind, which is what we all probably figured he’d say anyway.

Let’s do what I said in the first place. Really, just repeat what you’re doing (the response vocals). I think that’s the best. … Not as high as we were doing it.

As we enter the final few minutes of the song’s rehearsals for the day, palpable tension finally arises. George’s general objection is to the weak response vocals and undefined instrumentation in the bridge. Paul replies that “I’m just trying to get a bit we’ll try and sort of go right through. We keep talking about it.”

The next take, they do a call-and-response in the bridge, this time repeating John’s lines: “I’m in love for the first time (I’m in love for the first time)/Don’t you know it’s going to last (Don’t you know it’s going to last)…etc.

George still objects, and makes no bones about it, saying,”I think it’s awful. … it’s terrible.”

Paul and John both fire back, speaking over each other:

John: Well, have you got anything to supplant it?

Paul: OK, you’ve got to come up with something better, then.

George makes a suggestion to the guitar part/harmony (they’re being played together) that Paul calls “just too pretty,” which is interesting on so many levels — although among them that it’s true.

They can’t get through a take of the bridge before things break down. George keeps offering up little tweaks, but Paul doesn’t want to be slowed. Now, at least.

Paul: We make it better as it goes on. … We’ve just gone around like for an hour with nothing.”

George: [We’ve been just trying different] permutations.

Paul: I know, but let’s sort of move on now.

John: I’d like to hear any of them right once.

More stumbling through takes and Paul and John reach agreement on how the bridge should now sound, at least the lyrical combination. It’s a mixed message to George, too, since literally moments after saying it wasn’t the time to tweak the bridge, he decides it, in fact, is.

Paul: When [John sings] “Don’t you know it’s going to last,” we sing, “It’s a love that has no past.” Then we repeat “It’s a love that lasts forever” exactly, and then when you sing “It’s a love that has no past,” we sing “It’s a love that’s going to last.”

Got that? Not sure John did or really cared — he’s let this aspect of the song be managed by Paul all day as it is — but he replied simply “Yes, I agree.”

Got that? Not sure John did or really cared — he’s let this aspect of the song be managed by Paul all day as it is — but he replied simply “Yes, I agree.”

A pair of broken takes did result, blessedly, in an epiphany and a solution that stuck.

“Forget the last line,” George said right after doing just that and playing the song’s opening riff over where they had been shoehorning in a response vocal.

They repeat this part a few more times. We still have the other extra vocals in the bridge, but the riff sticks.

While Paul’s assuaged for the moment — “So that’s near enough for the time being” — John isn’t.

John: We found out that’s the weak bit [the bridge] so we tried putting voices on it. But it’s still down to the rhythm.

Paul: But it was always weak on your guitar. That’s the weak bit of the song. (It’s unclear here if he’s talking to John or George, or both).

Shortly after that exchange, we’re back after some kind of gap on the tapes, with a fresh attempt at the song from the top. And we clearly lost some discussion, because the bridge suddenly lacks any response vocals — but does retain George’s riff to end the section. This sounds like the “Don’t Let Me Down” we know and love, for the most part, even down to John not quite getting his own vocals straight.

The next (and final) take, we inch even closer, with Paul and George singing harmonies with John, not as a response to him in the bridge.

And with that, the band ends their 80-plus minutes (on the tapes, it was even more in reality) of “Don’t Let Me Down” rehearsals on a high note. May not have been the classic “eyeball-to-eyeball” collaborations John and Paul would do — especially with George so deeply involved. But clearly, even though it wasn’t exactly cordial, it worked. “Don’t Let Me Down” was a better song 80 minutes after they started rehearsing.

Paul then announces the next song they’ll try to work on — “Two of Us Going Nowhere On Our Way Home” — and we’ll find out soon enough just how much George wants to please him.

Well, he regains authority at the outset, at least, during a stretch that provides the first real look at the discord between band members that helped define the Get Back/Let it Be sessions.

Well, he regains authority at the outset, at least, during a stretch that provides the first real look at the discord between band members that helped define the Get Back/Let it Be sessions.