A half-hour or so into the January 10 Nagra tapes, the visiting Dick James finally noticed something unusual at Twickenham.

“Are we interviewing?”

“This is my bug,” film director Michael Lindsay-Hogg answered. “I carry it with me, always.”

Paul McCartney chimed in: “We’re just constantly on film these days.”

“Oh, I see. Something’s happening,” Dick finally concluded.

He was half-right: Something was happening soon.

George Harrison was the third Beatle to arrive at Twickenham on the 10th, continuing a pattern over the first week of the group’s January 1969 sessions. He was the first to leave a few hours later, and he wouldn’t return to this studio again.

Liberal as the members of the band were to speak their minds — or at least not be transparently cagey — with knowledge of film and tapes rolling (including Michael’s not-so-undercover portable mic), the Beatles had a secret they wanted to discuss, but they never went so far as letting the cat out of the bag or into the bug.

“Did Neil [Aspinall] ring you last night?” Paul asked earlier in the day, with Ringo answering in the negative. “Sad news on the wheeling and dealing scene. … I don’t think he wants to say much.”

Later, on John’s arrival, George goes into slightly further detail on the meeting of the Flocculent Four.

“Neil would like us to have a shave tomorrow” — a Saturday — “only because we’re busy every other day.”

George further discussed the upcoming meeting – spinning it as a positive, in contrast with Paul’s interpretation — without other details beyond the hopes of it happening at 8 or 9 in the morning “so we can have the rest of the day to ourselves. Neil was very excited.”

Closer, let me whisper in your ear.

John: Good news?

George: Yes, very. … It’s so good, he just told me briefly what it was. But I’d have to whisper it or write it on a paper and you’d have to swallow it.

Without further detail, George mentions John Eastman by name right as the microphone refocuses on Dick and Paul, clearly suggesting the meeting involved Paul’s future brother-in-law, whose legal counsel the Beatles received at some point in January 1969 regarding NEMS.

****

“Do you think if I paint this brown and put red on top it’ll look like like a cigar?” Michael asked of his spy microphone.

George: You wouldn’t see the red, just the ash.

Ringo: Hide it in one of those film cigars.

MLH: Yes, like Groucho Marx.

Perhaps the inventive director wanted to get his bug in the ear of Apple Electronics’ Magic Alex.

“To change the subject,” Glyn Johns asked as the morning continued, “That phasing device that Alexis [Mardas] has built, have you actually tried it out?” (Glyn — along with the Beatles — are counted among the pioneers of the technique.)

“He just comes across things as he’s designing,” said George of Alex. “He just designs it and then he says, ‘Oh, yeah, I’ve done this.’ But he hasn’t actually made it because he’s busy building recording studios.”

Everyone would soon learn “building” was a loose interpretation. More on that when the action shifts to 3 Savile Row.

At Michael’s request, George retold the origin story of Alex’s relationship with the Beatles.

“He met John Dunbar — or John Dunbar met him. Alex asked if he could stay and build a light machine for the Stones tour. So he stayed and did that. … And then he met John, and then he met us. And he’s been there ever since.”

“Is that device he’s going to put out on records going to work?” Michael asked. “Where you can’t tape it? Great idea.”

Home taping is(n’t) killing music. (Source: Ebay)

Ringo agreed with Alex’s primitive, unrealized copy-protection scheme, but said John was against it — why would the Beatles want to stop the kids from getting their hands on music? But John held the minority opinion.

“In America they have those cassette tapes,” George said. “That means its easy if somebody buys one and then rolls off their own 4 million and sell it. Everybody loses out on that because people bought it, and yet some cunts made all the money for doing fuck-all except thieving it.”

The idea of an intrusive “This is an Apple Record” messaging dropped into the record was embraced too. “It’s a good idea,” Michael said, “because if you’re rich enough to buy a tape recorder, you’re rich enough to buy a record, really.”

(He certainly wasn’t wrong, they didn’t come cheap. But if the bootleggers were running off 4 million copies, they were aiming too high — in 1968, the Beatles “only” sold 3.47 million records total in the U.S.)

Conversation quickly shifted from Alex — “We should get all his tricks,” George said — and the record business at large to the immediate business at hand. And it gives a clear picture to George’s state of mind in the hours before he quit the Beatles.

“I’m getting tired … just coming here, I’m bored stiff.” Openly frustrated with the directionless situation and feeling trapped at Twickenham, George asked if the group was still planning on rehearsing the next day, which would be their sixth straight at work.

Michael doubted it — he wanted to get rid of a nagging cough, and anyway, “I think we’ve had quite a good week.” This was, remember, the last day of their first full week for these sessions, and just their seventh day in the studio overall.

At this point, John, who was pretty much always the last to arrive to Twickenham, did just that with Yoko. Again, Michael touts his discreet yet disclosed microphone.

“If anyone says anything interesting, will you remember it?”

“Dick James is a fascist bum,” John replied loudly, though clearly out of earshot of the publisher, who was in the midst of another business-related exchange with an inattentive Paul, touting things like “the consistency of earnings.” Referring to Dick as “pig” moments later, John’s feelings were certainly clear, but he also wasn’t confronting him, this morning anyway.

Whether it was playing for the cameras (and microphones) or just trying to keep the darker side of the business out of the studio, John was upbeat and friendly in chatting directly with Dick.

Having hyped the “tremendous music book trade” and briefly addressing and then downplaying a published quote from the Daily Mirror from the previous weekend — “Will the Beatles record any of [the songs from the Lawrence Wright collection]? Said Mr. James: ” Now, that’s an interesting thought. … I doubt it, but it would be a gas if they did!” — the conversation turned as at often did, back to television.

“You likely to be home tomorrow evening, watching television?” Dick asked John. “The Rolf Harris Show, Vera Lynn is on singing ‘Good Night.’”

John sounded sincerely charmed his song was getting the prime-time treatment. “Oh, she’s doing that? I thought she did ‘Fool on the Hill’.”

Alas for John, “[‘Good Night’ is the] B-side,” replied Dick. “We put them back to back. … it’s a nice medium waltz. It sounds like “True Love,” that kind of feel, makes it very commercial. (Because everything in Beatles history ties together, it’s worth nothing seven years after this conversation, George himself recorded “True Love” for his 33 1/3 LP, albeit without the original waltz arrangement.

Another cover, Arthur Conley’s version of “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da” — as likely pictured in one of the photos from the Get Back Book that accompanied the Let It Be LP (look for the ATCO label) — drew George’s interest. “That’ll be the big American one? … It’s gone 50 now? Great!”

After fishing for a cigarette, Dick steered the conversation with George to a deep shared interest: cars.

“I would never have a Yankee car, not for this country,” Dick said. “They’re just a bit too big. Nineteen-feet long. ”

“And they’re so … rubbish,” George replied.

In particular, they hated the Cadillac Eldorado.

George: You look at it, and there’s all this plastic.

Dick: A load of bull all over the place.

George: Even the wood in it is like wallpaper.

They could hardly find a redeeming characteristic in American cars. “I can’t stand brakes on American cars,” Dick said, with George likewise bemoaning power brakes. “I nearly killed myself,” Dick said of owning a Buick Skylark.

Ultimately, Dick ended up with a four-door Rolls Royce Silver Shadow.

Not quite the driver and six months away from wrecking his British-made Austin Maxi, John broke to tell Paul, who had finished his piano stint and rejoined the others, the good news: “Vera Lynn’s done ‘Good Night’ and ‘Fool on the Hill.'”

After Dick recapped Lynn’s promotional schedule, Paul was ready to really get to work.

“OK, should we start?”

Dick left the scene having promised Paul to “send some discs down.”

And with that, the group returned to work on what had the potential to be their own next disc and the next batch of Northern Songs.

****

“If you’re listening late at night/You may think the band are not quite right

But they are/They just play it like that”

The second verse of “Only A Northern Song” was written almost two years before the Beatles’ January 1969 sessions; coincidentally, it was released on the Yellow Submarine soundtrack LP 72 hours after the events of this post (in the U.S. — it came out in the U.K. a week later).

The Beatles most definitely were not quite right on January 10, 1969. George Harrison, John and Paul’s bandmate since 1958, before anyone was a Beatles, would soon the Beatles and there’s nothing right about that. But in a sense, they were quite right, they “just play (it) like that.”

There are multiple reasons George left the Beatles on January 10, but Dick James wasn’t one of them, despite the timing of his visit and the publisher and Northern Songs historically irritating George to the point it inspired a song. Dick wasn’t a true villain in the Beatles’ story contemporaneously, and he wasn’t a divisive figure to the group until he chose to leave their orbit by selling off Northern Songs to ATV a few months later. To this point relationship may have been deteriorating, but hadn’t in any way collapsed.

Status as “a fascist bum” notwithstanding, Dick — a generally respected elder like George Martin or Brian Epstein — could still talk music-hall numbers with Paul and Ringo, and cars with George. This visit said more about the Beatles themselves than Dick, reinforcing the group’s innate ability to isolate business from pleasure, whether the pleasure was making music amongst themselves or happily discussing frivolities with a man George later called a con man and thief. And even when talking business — like ownership of “Boomps-A-Daisy” and how “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da” covers fared on the charts — conversation could easily veer to power brakes or the kids at home.

It may have been in Hunter Davies’ words, but in his authorized biography of the Beatles that was published only a few months earlier, he conceded “they all loved Dick James.”

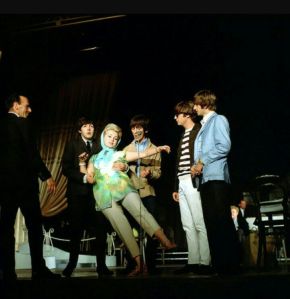

The same 1968 Apple promotional film touting Magic Alex’s electronics department (as posted above) also serves a glimpse of Paul and John confronting Dick over money, with Paul firmly directing Dick to “go away, and you come back with something which you know won’t start this argument again.” Months later at Twickenham, with Dick not even aware the Beatles were filming their sessions, there was no such encounter. The argument wasn’t started again, but there wasn’t any change in their arrangement, either.

As Derek Taylor wrote in “As Time Goes By“: “Dick never liked rows with the Beatles and I cannot blame him.”

***

The scheduled meeting for the next day that so excited the Beatles didn’t materialize. They ultimately met at Ringo’s house on January 12 under completely different circumstances.

Paul McCartney began

Paul McCartney began