We pick up the scene where we left off from the last post, Jan. 7: On our own at the holiday camp, as The Beatles and film director Michael Lindsay-Hogg wrestle with the question of the band’s motivation in the post-Brian Epstein era and struggle to find a live-show venue amenable to all parties.

Michael Lindsay-Hogg continues the discussion by posing a question to John, Paul, George and Ringo that seems like it has an obvious answer. After all, since Candlestick Park in Aug. 1966, The Beatles quite famously haven’t staged a concert, instead embracing all the luxuries being a full-time studio band offers.

“But do you still want to perform to an audience?” he asks. “Or do you just see yourselves as a recording group.”

That’s a simple enough question that really does cut into their motivation, not only for these sessions but for their own reason for existing at this point in their history. Paul responds, speaking over the director, saying that an audience indeed should be involved with whatever it is they’re trying to accomplish with this project.

“I think we’ve got a bit shy,” Paul says before the cameras. “I think I’ve got a bit shy of certain things, and it is like that.”

Lindsay-Hogg, who so badly wants to stage a grand return before an audience for the group, again suggests departing from their past experiences. Get back to where you once belonged? Not now.

MLH: Maybe the difficulty is also getting up in front of an audience with all you’ve done in front of audiences, and trying to get something as good, but maybe not the same thing. And that’s a very hard thing to get back. In other words, you mustn’t think of getting back what you had.

The audience has indeed grown up along with the Beatles — who are all in their late 20s by now. Paul says they’re all searching for a “desire” to perform and achieve.

And just then, Paul comes out and reminds everyone how little they enjoy working together. After all, just three months earlier they were together at EMI Studios to finish up the White Album sessions, so the memory’s fresh.

“With all these songs, there’s some really great songs, and I just hope we don’t blow any of them,” Paul says. “Because, you know often, like on albums, we sometimes blow one of your songs cause we come in in the wrong mood, and you say, ‘This is how it goes, I’ll be back,’ and we’re all just ‘chugga-chugga, chugga-chugga’ [sounds of guitars].”

So there’s just a little more proof that the Get Back sessions weren’t the specific spark that led to The Beatles’ breakup. They had already been known to mail it in on occasion for a few years now, and Paul wasn’t shy to admit it.

But Paul’s remarks didn’t drop like a bomb — they were simply acknowledged silently as the conversation resumed, with Lindsay-Hogg’s continued insistence to use a specific live-show idea as a rallying point.

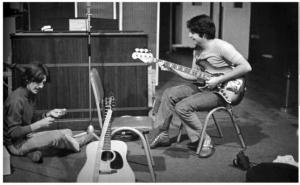

1968, White Album sessions: “You can do anything that you want, Paul, anything you desire.” (Photo by Linda McCartney)

George Harrison wouldn’t bite. His response is damning, striking at the essence of the debate of what The Beatles are, post-White Album. Are they a cooperative? Each others’ backing band? Something in between? And what should they be, in their eyes?

What they definitely aren’t, according to Harrison, is an effective live group.

“Really, I don’t want to any of my songs on the show, because they just turn out shitty, ” he says. “They come out like a compromise. Whereas in a studio, then you can work on them till you get them how you want them.”

So for a live show, George just wants to be the band’s lead guitarist, nothing more.

Paul, audibly disgusted at that remark, is having none of it, still believing in The Beatles.

Last year, you were telling me that ‘You can do anything that you want, Paul, anything you desire.’ … But you’re saying before the show is finished, and before we’ve done it … letting forth this word of, ‘They’re going to come out a compromise.’ …

I really think we’re very good, and … if we think that we want to do these songs great, we can just do it great. Thinking it’s not going to come out great, you know, that is like meditation. Where you just get into a bummer, and you come out of it, you don’t go through it.

Paul hits George where it hurts, referencing his beloved meditation.

Paul continues, hitting home the point that even he’s fed up, too, but it shouldn’t mean avoiding whatever challenge they’re setting up for themselves.

Paul: [Presumably to Ringo]: So you’re sick of playing the drums, we all got to say, ‘We’re sick too, pat pat.’ It’s all the same and go through it. There’s no use just saying, ‘Well, fuck it.’

MLH: … What’s wrong about doing the show here [Twickenham] is it’s too easy. Like, when we were in the car looking at locations at the glorified boutiques … then Denis [O’Dell, film producer] said, ‘Why not do it at Twickenham,’ and Neil [Aspinall, Apple manager] said, ‘Why not do it at Twickenham, because it’s so easy.’ … I think that’s wrong.

I don’t mean we should put obstacles in our way, but also in a funny way, like you were talking about Brian [Epstein]. … We should have some force to resist. But just doing it in the backyard … it’s too easy. And we’re not fighting it. There’s no balls to the show at all, I’m included. There’s no balls to any of us at the moment. And that’s why I think we’re all being soft about it.

Credit the director for recognizing the dire straits at hand. He’s right: Without a show at this point, the sessions would effectively have no real purpose and would cease. Obviously, no one wants to be there merely to start recording a new album, with the possible exception of Paul.

“If you all decided to do a show, it should be the best show,” Lindsay-Hogg says. “You are The Beatles, you aren’t four jerks. And that’s really my job. Because when you’re playing your guitar, they’re not going to be thinking about those millions of unwashed.

“I think we’re all being soft. It’s all too easy.”

Laughing, Paul asks what kind of obstacles would the director suggest the group face.

“Well, I don’t know,” Lindsay-Hogg replies, “But that was the pep talk for the morning.”

With hindsight, we can call out Lindsay-Hogg’s instincts. The Beatles had the knack to make the “easy” way work and deliver something iconic. After all, a little more than three weeks after this conversation, the band merely climbed from the basement studio at 3 Savile Row to the roof of the five-story building for the much-debated live show. George, as he suggested on this day, was just the guitarist, and none of his songs were played.

Later the same year, The Beatles took the easy way out again, naming their subsequent album after the street they recorded on — Abbey Road — and shooting their cover just outside the studio’s door.

For The Beatles, sometimes easy worked.

The Get Back sessions story – what we’re telling here via the Nagra reels — can’t be told completely without the context and seen through, in part, the lens of the rocky White Album sessions. Ringo left the band three months into recording The Beatles. It took only eight days for George to flee the group at Twickenham. Just listen to the group’s own words on Jan. 7, 1969.

The Get Back sessions story – what we’re telling here via the Nagra reels — can’t be told completely without the context and seen through, in part, the lens of the rocky White Album sessions. Ringo left the band three months into recording The Beatles. It took only eight days for George to flee the group at Twickenham. Just listen to the group’s own words on Jan. 7, 1969.