“It is no criticism of a thoroughly professional work that the Beatles will doubtless make sure it is out of date in a very short time.”

Writing for the Liverpool Echo on Sept. 30, 1968, Jonathan Cundy pointed to the velocity of the Beatles’ lives and musical innovation in reviewing Hunter Davies’ authorized biography that came out the same day.

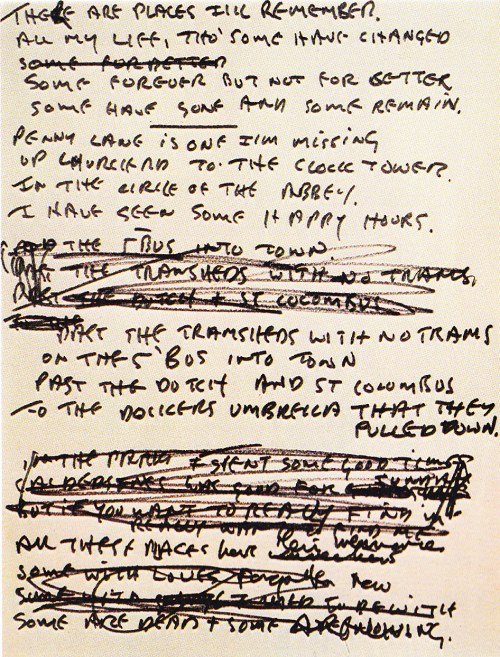

No matter where they serve their guests, they seem to like the kitchen best: The Threetles in Anthology.

In real-time, the Beatles soared at the speed of light. Together or apart, across the 20th or 21st century, the history of the Beatles is fluid usually by their own design. And here we are talking about that again, nearly 60 years on. It wasn’t just their music and style that was constantly reinvented, so has their history in their own telling. Chisel Jonathan Cundy’s line in stone, it stands as an eloquent, evergreen statement on the Beatles biography business. Tomorrow really never knows.

I’m grateful we were served a new iteration of Anthology on Disney+ at the end of November 2025, grateful for enhanced visuals (clunky AI bits aside) and sound, because the more people are exposed to the Beatles and their history, the better. I wanted to weigh in and offer my immediate and subsequent impressions after watching Anthology ‘25. (I’m mainly writing here about the documentary, not the album set or book, although I will refer to both at times). In preparing for this post, I rewatched a broadcast version of the 1995 Anthology on the Internet Archive, my own DVD copies of the 2003 version and the 2025 streaming Disney+ cut. I also used this excellent resource documenting the changes across ’03 and ’25.

Watching the new Anthology exposed some issues in the original Anthology that I hadn’t really internalized after all this time. So I’m here to stare a hole through that version, too.

No time is a good time for a broad Beatles history. It’s always out of date in a relatively short time, even for a band that hasn’t worked as a quartet since 1969. We — the researchers, the curious, the informed — along with the somewhat fickle nature of the surviving members, estates and Apple itself, will always make that the case.

At least they acknowledge the problem. Here’s Paul as quoted in the Oct. 23, 1995, issue of Newsweek, in advance of Anthology’s release (I’ve held that magazine in my basement for decades, knowing I’d need it for this post one day):

I don’t know if you ever understand anything. That’s what happened at the end of the ‘Anthology’: I don’t understand it all any better than I ever did. But it’s all in one place now. That’s the thing.

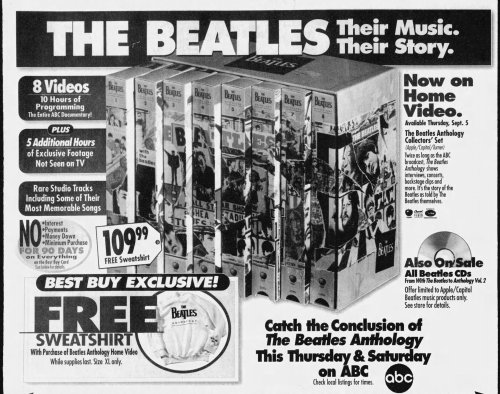

I love the Beatles Anthology, it’s a critical document. I watched it on broadcast TV (for me it was ABC in the United States) during its first run 30+ years ago. Before that I learned the ropes as a teenager watching The Compleat Beatles all the time, usually starting at the “Strawberry Fields Forever” segment but often consuming the whole thing. That was my Beatles baseline when it came to history entering into the Anthology era. I read plenty of books, owned all the albums and a few bootlegs. I considered The Compleat Beatles as unimpeachable Beatles history, even if it wasn’t directly from Henry the Horse’s mouth. I think it influenced Anthology in various subtle ways, too.

I recorded Anthology off TV, explaining why I never bought the official VHS release in 1996. But I did get the DVDs when they came out in 2003, and it’s been a valuable research tool especially in tandem with the companion book that came out in 2000. A Beatles opinion may be mutable, but at the same time it’s gospel.

Paul, George and Ringo conducted interviews for Anthology in a narrow early-1990s period, and what they said for Anthology ’95 was drawn from the same interview inventory used in Anthology ’96 (VHS/Laserdisc), Anthology ’03 (DVD) and Anthology ’25 (Disney+), even if what was selected varied.

I hadn’t internalized how gone – like far gone — John Lennon comes off in Anthology until carefully rewatching it in Winter 2025. His absence is really contrasted by George Harrison, who isn’t with us either, but is vibrant and contemporary in Anthology. George was the youngest one interviewed in the 1990s, after all. He reminisces along with Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr over decades gone by. He can directly debate the others.

“We’d all had enough time to breathe,” George said in Episode 9. “And I think it’s much easier to look at it now from a distance.”

John’s memories are airdropped in, and I can’t see past that anymore with the added distance we have from those clips. John’s contributions feel slight, relatively and understandably.

Obviously, John’s Anthology recollections are forced to come from decades earlier, culled from copious interviews, but those spanned a larger period of time and a wide band of moods. Jools Holland, who interviewed the other Beatles for Anthology, didn’t get to ask John a single thing, leaving his reactions shoehorned in, speaking to different media at different times via different prompts. John was never afforded the luxury of being relaxed for these interviews – he didn’t pilot a boat or sit poolside whilst reminiscing. And he didn’t have the distance that helped George. John’s moments come off lonely.

(Facing the same dilemma, the producers of last year’s Becoming Led Zeppelin used a similar approach to Anthology, mixing new interviews for the film with the three living members with archival clips from the late John Bonham. But at certain points they showed Jimmy Page, Robert Plant and John Paul Jones listening and reacting to Bonzo’s quotes, humanizing the moment and bringing the drummer just a little bit more into the conversation.)

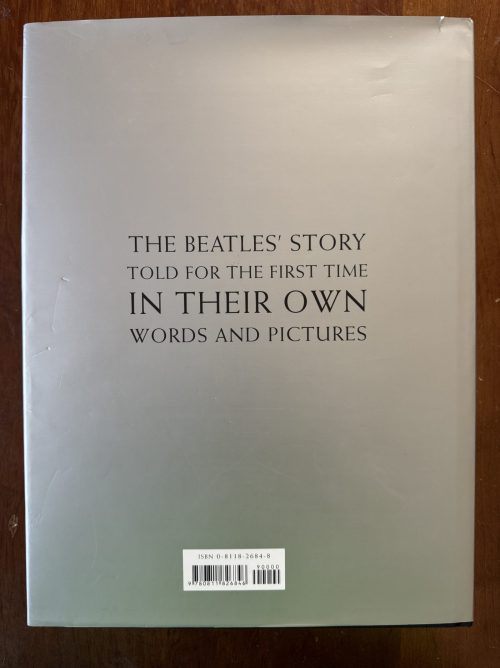

Across every release and in subsequent marketing, the Anthology brand held strict that the story was almost exclusively in the Beatles’ own words (e.g., look again at the above Best Buy ad). It’s even in big letters on the back of the Anthology book. The only new interviews outside the Threetles came from the deep inner sanctum of Neil Aspinall, Derek Taylor and George Martin. That meant hearing nothing from the five wives (Cynthia Lennon, Yoko Ono, Linda McCartney, Pattie Boyd and Maureen Starkey). Nothing from sympathetic figures like Billy Preston or Astrid Kirchherr, much less villains Allen Klein or Magic Alex.

Even a genuine Beatle was forbidden to retell the Beatles’ story, with Pete Best silenced in Anthology. All the above were alive and available to be interviewed in the early 1990s (Maureen died late December 1994). But if this is “their” story, the omission can be justified.

(Cynthia’s manager at the time disagreed, telling Newsweek, “They’ve made the be-all and end-all of the Beatles story without her! As if she wasn’t there! It’s ridiculous!”

Notably, according to multiple contemporary accounts, Yoko was offered the chance to be interviewed, but she turned it down. Would her inclusion have opened the door to the others and steered the entire documentary in a different direction? Would she purely have been a one-for-one surrogate for John as a relaxed 1990s interview? Or was it simply for a first-person perspective on her offering John’s demo tape to the band in the early 1990s, only? We’re left to guess.

The snapshot of the six contemporary interviews are memories based after nearly a quarter-century of post-breakup reflection. It’s the same kind of snapshot we’re left with reading Davies’ biography, which ends with John “happily married” to Cynthia. When the book came out on the last day of September 1968, the Lennons had already been to divorce court. Yoko isn’t mentioned in the original edition.

Davies was conscious of his book’s obsolescence, concluding it with this passage:

Doing a biography of living people has the difficulty that it is all still happening. It is very dangerous to pin down facts and opinions because they are shifting all the time. They probably won’t believe half the things they said in the last four chapters by the time you’ve read them.

Jools took the task of interviewing the Threetles with the appropriate attitude of a serious journalist. From his enjoyable 2007 memoir, Baldfaced Lies and Boogie Woogie Boasts:

The first person I went to interview was Paul … I then moved on to George, and then Ringo. At one point all of them individually mentioned a van they all hated travelling in, but each of them remembered the make and colour of the van differently. I brought this up with Chips Chipperfield, the producer, and he said, ‘Silly detail. Doesn’t matter.’ But my policeman’s mind had already gone to work and I was thinking, ‘Well, it might be a silly detail to you but, if they’re not remembering the same facts about this one horrid van, it might cast a shadow over their memories of other matters?’ And this was borne out throughout the course of the Anthology.

…

Occasionally I would say, ‘Can I just compare your evidence to the evidence put forward by your co-members?’ But they all found their differing memories amusing.

It was a feature not a bug. It’s who they are.

I can be as skeptical as anyone, but the Beatles controlled their narrative from the moment they were able to, and I think they should have — it’s their own history. And that narrative was everything from what they said in radio interviews to the clothes they wore to how they picked the running order of their albums. It’s how they chose to present themselves. Just like they chose the content for Anthology.

We’ve been in the Anthology era nearly as long as the pre-Anthology era existed. Why shouldn’t they update it where they see fit, attract a new audience and take advantage of the better technology? No disrespect to those who are, but I’m not a purist. Stream away, repackage and resell deluxe editions, scrape the bottom of the barrel and I’m on board.

So I have no issues conceptually with the many revisions applied to the new Anthology, from a libertarian angle. Also, I like change, and I’m not stubborn in my day-to-day life (I recommend it!). That said, they should not sell Anthology in 2025 as the same product that existed previously. This isn’t the same as restoring A Hard Day’s Night for Blu-ray or putting the 2009 remastered Rubber Soul on Spotify.

Let the Beatles tell their story, and at the same time, we can tell their story too, on blogs, podcasts, books, everywhere we can communicate.

Given that it’s my home turf, I want to dig a little bit into the Let It Be/Get Back sequences (primarily) for demonstrative purposes, but I’m sure whatever points I make translate across eras and the documentary.

For those keeping score, the Get Back segment clocks in 5-6 minutes longer on Disney+ vs. the DVDs and the original ABC broadcast. So for a series that was shortened from the DVDs for streaming, this period is actually longer.

Here’s what’s NEW in ’25:

- The big add was the January 10 jam with Yoko, post-George’s walkout. At least through the late-70s, George was under the impression this segment made the final cut of Let It Be, referring to Yoko’s “screeching number” in the film in a 1977 interview. Why now, and not in 1995/2003? Maybe George stood in the way then, and its use in Get Back broke the seal for its use here. Whatever the reason, it definitely is a positive addition, reflecting the chaos of George’s departure and dovetailing with the section on Yoko’s relationship with John and the band.

- Another excellent, important addition was the “final bulletin” segment, Paul’s fake news show that would break the Beatles’ split. Enveloped by other 1990s-era quotes about a breakup in the air, this concrete and contemporary discussion really ties the room together as a weather forecast for the Winter of Discontent. If you’re keeping track like me, you’ll note the end of this sequence slightly differs from what is in Get Back. This Anthology edit is the real deal, what you hear on the Nagras.

- Even though George walked out and Yoko sang from his cushion, George still said it was “a lot of water went under the bridge” and “everyone’s good friends and has an understanding of the past.” George said this in the 1990s, but it was not included in the first passes of the series. It certainly fits the “story of friendship” the Beatles have sold as the brand in recent years.

- Paul’s concern that once the sessions ended John would be “off in a black bag” instead of following up with the band was another good addition. More fuel to the argument that the breakup was inevitable.

- Also fitting the concept that the four of them could be the only ones who could understand each other is Paul’s worry Billy was joining the band. He was worried in Get Back — we heard his concerns then — and he didn’t change his tune come the Anthology interviews.

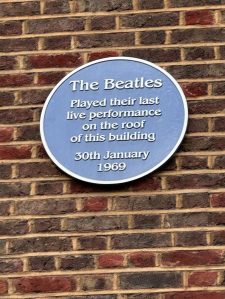

- Incredibly, one of the greatest moments in filmed Beatles history — “I hope we passed the audition” — was not in any previous iteration of Anthology. So this is a layup, a must-add. The mind boggles how this wasn’t in there before.

- As the segment neared conclusion, George said the group became stifling and restrictive and that “it had to self-destruct.” It’s not an earth-shattering line, but just adds to the inevitable breakup.

I found a few significant modifications, too:

- George describing the Get Back sessions as his “Winter of Discontent” — such an amazing, biting line, still — was shifted from before the “I’ll play if you want me to play” argument to after it. I don’t see this as anything other than improving the flow of the story. I’m on board.

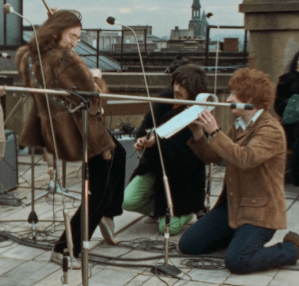

- While the Beatles play “Don’t Let Me Down” on the rooftop, the DVD shifted to street-level audio while the camera showed the audience on Savile Row. Disney+ restored the rooftop audio for those scenes — and that matches the original broadcast. It’s a superficial change, but worth noting.

- Paul’s fireside Army buddies story was moved to immediately before the wedding segment, another logical change for story flow.

- “Can we giggle in the solo?” The addition of John’s one-liner prior to Let It Be is another way to lighten the mood (as it was when he first said it in 1969).

Looking at those lists, a lot was changed! On balance, I think the updates to this segment are positive, but it’s only positive in the context of Anthology as it had existed. Here’s the real problem: The story Anthology tells of the January 1969 period is really convoluted, especially on the heels of 2021’s Get Back documentary, which now is a well-known quantity for the Beatles community, old and young, immersed and casual. Yet Anthology tells the “original” story of the January 1969 sessions, which was never really right.

I wrote about this at length. Let It Be (the film) dictated opinions for half a century, influencing idiots like me to actual living, breathing non-idiot Beatles. I think it’s clear that Let It Be as an artifact influenced Anthology’s production in the 1990s. The “I’ll play if you want me to play” argument was the deliberate showcase of the Get Back sessions’ dysfunction in Anthology, the jump-off for the breakup conversation, and a reinforcement of what was said otherwise for decades. It continued to define the period until the Get Back documentary era.

I think that “row,” as George describes it, stays as a centerpiece in the new Anthology simply because it’s the one specific incident he comments on directly. We’re tied up because of the resistance to expand beyond the 1990s interview inventory.

Why not also show George suggesting the group “have a divorce” on January 7, 1969? Or saying he could work on a solo record January 29? Both segments were in Get Back and ready to load into Anthology, and either scene (or both!) would be better confirmation of the breakup vibes in January 1969 than a fleeting argument that happened to make the Let It Be film.

The changes to January 1969/breakup sequences went halfway in Anthology ’25, and I think shifting focus off the “I’ll play if you want me to play” scene would have been seen as tearing apart original production, even if, like some of the other changes, it would have proved clarifying.

Here’s Paul in August 2021, in advance of the release of the Let It Be LP reissue, shortly before Get Back came out, too:

I had always thought the original film Let It Be was pretty sad as it dealt with the break-up of our band, but the new film shows the camaraderie and love the four of us had between us. It also shows the wonderful times we had together, and combined with the newly remastered Let It Be album, stands as a powerful reminder of this time. It’s how I want to remember The Beatles.

Great news, even if we didn’t get the reissue of the Let It Be film until 2 1/2 years after this statement. I have something in common with Paul McCartney: This era is how I want to remember the Beatles, too! But it’s also the same period Paul describes in all the Anthology versions as “showing how a breakup works,” and you wouldn’t think that’s how he wanted to “remember the Beatles.”

This wasn’t Paul speaking off the cuff. All four Beatles maintained for a long time that January 1969 was toxic, two of them until their death. So let’s call them mercurial.

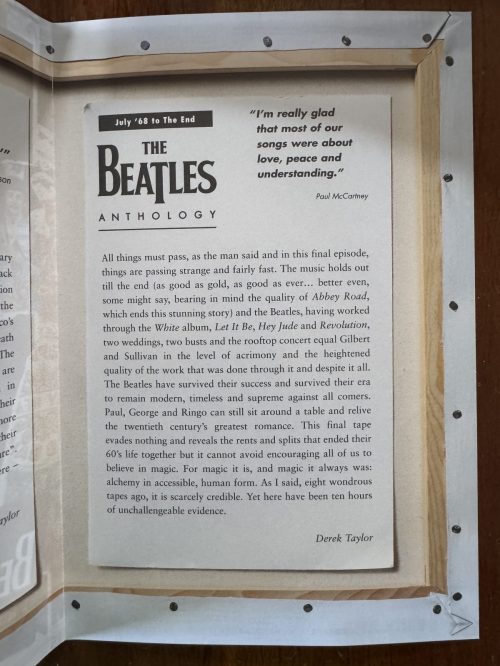

If you check the Anthology VHS and DVD liner notes, Derek Taylor concluded the text on the final episode by describing the Beatles’ career arc as “scarcely credible.” The band we’ve known for all these years conceded what we’ve known for all these years.

“Yet,” he continued, “here have been ten hours of unchallengeable evidence.”

The number of hours fluctuated with every release of Anthology – a point of contention nowadays — but the concept holds true: Beatles history borders on the unreal. And we have to admit at the same time the storytellers can sometimes be, to use his words, scarcely credible.

(By the way, one other thing we lose with the streaming-only focus is the beauty of liner notes as a medium. But that’s another, frankly sad, story.)

Deliberately, I only studied in detail the Get Back and surrounding sections for this post, but I’d imagine that if I did the same for another period, I’d reach similar conclusions. I know all about the “cripples” bits and Hamburg condom story being pulled. I took note of the addition of ’90s Ringo saying he and Barbara are inseparable like John and Yoko, and all the extra smiles now in the final Tittenhurst clips. The addition of John’s original “Yellow Submarine” work tape from Revolver deluxe is great and exactly sort of thing we should have after its discovery a few years ago.

I like a lot of the changes! Still … if you’re going to change, really commit to the changes.

I think Apple should have torn it all down produced a completely new Beatles documentary rather than present 2025 Anthology as the unimpeachable, singular career-spanning Beatles documentary. Davies’ biography was obsolete the day it was released. And that’s OK! Beatles Anthology ’95 is obsolete too. And that, likewise, is OK. If we think it can be better, let’s give it a shot. Anthology can be the Beatles’ history circa the turn of the century. Why do we have to work in that documentary’s template alone?

I think it’s been nice for us and the public to forget about the Beatles for a while, let the dust settle and now come back to it with a fresh point of view.

That’s George speaking in Episode 9 again, and making my case.

I haven’t seen a quote from Peter Jackson, whose team restored Anthology, but I did see Oliver Murray, the Episode 9 director, say this, which makes me think it was an overall strategy across Anthology ’25:

It was important to me that the pool of material we were working from had a time and a place. It was made in 2025, but the world that we’re absorbed in is from anywhere between ‘91 and ‘95.

And this is where I’ll plant my flag. Why did this world have to be from 1991-95? I know, it’s because it’s part of Anthology, a product of 1995. But this doesn’t have to be.

We’re in Theseus’ Paradox, if I can overdramatize this. How many pieces of the Beatles’ ship need to be replaced for it not to be the Yellow Submarine anymore, so to speak? Add this clip, shorten this other one, reorder something else — after how many revisions is it not the same documentary?

They promised the “ultimate form” of the product. I think we just got “another” form of it. I can wrap my head around removing some of the more PC-related issues, and I understand killing the Apple Boutique segment (for instance) because it doesn’t flow well or loom large in their legacy. (They could have at least put something like the Apple Boutique segment as a little bonus extra on Disney+ — it already was produced, is pretty harmless and is still part of the history.)

Anthology doesn’t cover anything between April 10, 1969, and 1994, the Threetles sessions. And then nothing after teasing the aborted “Now and Then” session in Episode 9. John Lennon doesn’t die in Anthology (neither does Stu Sutcliffe, for that matter). I get it – it’s not the John-Paul-George-Ringo Anthology. It’s the Beatles Anthology, and John is alive when the Beatles split. In Anthology’s world, the Beatles reunite, but without any context how or why.

“Having not done it for so long, you become an ex-Beatle,” Paul said in Episode 9. “But of course, getting back in the band and working on Anthology, you’re in the band again.”

But then he wasn’t in the band again. They chose not to finish the third song in the 1990s. We know how “Now and Then” turned out. Is this new Anthology for posterity or not? If it is, why end on a cliffhanger? Davies had an excuse when his book came out saying John and Cynthia were happily married, and with no mention of Yoko: He had to send his manuscript to the publisher. “Now and Then” came out two years ago, and this isn’t print. It’s another example of the new Anthology going halfway with that ending.

Maybe a new documentary can be honest about that too: If the Beatles are still together today, then we’re still in its history, and 1970-2026 is part of their history. Embrace it. I don’t mean have a segment on Flowers in the Dirt or John’s immigration case.

Paul said “we were at war” in Episode 9 — so show it. The lawsuits. “Too Many People” and “How Do You Sleep?” Show the collaborations, too. The Ringo LP. Clapton’s wedding. Even if they still don’t want to explicitly mention the deaths of John and George, present “All Those Years Ago” and Paul and Ringo (and Billy, and so many others) at The Concert For George. The Beatles enjoyed shared history after 1970 that gives important background.

Beatles history doesn’t have to be viewed perpetually from 1995, and that’s how Anthology as it stands is presented. It’s an arbitrary endpoint now.

Fly in post-breakup clips from the other Beatles, not just John. Paul in ’76 or Ringo in ’77 or George in ’71 – any of those clips (for instance) would have helped ‘70s John not come off like such a remote figure who didn’t get to have the same closure the other three had. No one could bring John to the 1990s, but they could have brought Paul, George and Ringo back to John’s ‘70s. Isn’t that what they did for “Free as a Bird,” “Real Love” and “Now and Then” anyway? The Threetles played John’s songs and were constrained by his limitations, not the other way around.

(Note that Paul took this very approach with his new Wings memoir, using a wide range of quotes over decades for the oral history.)

Peter Jackson and the technology he’s brought injected incredible life into the Beatles history, and also some questions. Do we want a Beatles history taking advantage of the advances, or improvement to the already existing Anthology? I personally don’t want an original-flavor Anthology that’s altered beyond whatever would qualify as “cleaning up” to account for today’s mediums (streaming, Blu-ray, etc.) I’m fully contented to have it be a product of its time, like Let It Be — which was indeed just cleaned up in 2024 — was as a complement to Get Back (and vice versa). But moving around quotes, removing some and adding others, leaving a bit of old history in and generally shortening the experience isn’t presenting the original document. Knowing the history I know, this feels incomplete.

I think a new Beatles history documentary could play a part in another revitalization of the group in the way the first Anthology did and how Get Back did, while also respecting the fact we’ve lost half of the band too. We may need to wait awhile until only estates are left to have a say. But it could take a replacement of every piece of the ship to truly rebuild and create clarity in their history.