Far from chaotic, the Get Back sessions, if anything, could be defined by its routines. Paul arrived early to play piano, and then pretty much ran the rehearsals. George’s songs — whether written overnight or brought back for another day — were a slog for everyone else. John didn’t have much new to offer, while Ringo did Ringo things like participate in conversations and keep the beat. Turn the page to the next day on the calendar, and do it all again.

Beyond music, the daily pattern underlying the scene centered around discussion of the live concert the Beatles were trying to put together. At once a footnote to the songs, the show was simultaneously the purpose of these January sessions and thus ostensibly what mattered most. The push and pull between director Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s wanderlust and the group’s default stance — to stay put — was a constant. And the more they couldn’t settle on a British venue, the closer they collectively moved toward simply staying in the very room where they were rehearsing and ruminating.

January 8, 1969, then, was no different than so many other days the Beatles spent at Twickenham the first half of the month. Discussion about the concert surfaced late in the work day, concurrent with Paul introducing the unfinished “The Long and Winding Road” and “Let It Be” to the rest of the band for the first time, and with their initial attempts at a full-band arrangement.

Yet now, to stage the “honest” sound they sought to achieve these sessions, the Beatles began to consider an ersatz solution. Rock and roll begets rocks, or something imitating it, at least.

Denis O’Dell (left) with Ringo at The Magic Christian shoot. Photo from O’Dell’s book, At The Apple’s Core.

“If we try to cover all this (Twickenham’s sound stage) and build caverns and caves, it’s nice, you see,” said Denis O’Dell, the head of Apple Films.

Why perform at the Cavern in Liverpool for the nearly 300th time, when you can simply craft your own cavern indoors? (Please don’t answer that.)

Denis had been in the film industry since before the Beatles were born, and his association with the group began in 1964, when he was associate producer on the A Hard Days Night film. It was the start of a mutually beneficial partnership to this point, which included How I Won the War (associate producer and John starred), Magical Mystery Tour (producer) and led to his appointment as an Apple executive.

Of course, you already know his name (but have to look up his number) from his time at Slaggers, and do note he is NOT related to Miss Chris O’Dell.

Denis had appeared sporadically on the tapes to this point, and here it dovetailed with one of the first times John seemed even marginally interested in what was going on with the live show.

“Then we could do what we’d like with a backing,” Denis told John. “Go black, or stark or something. Then we could control all our lights from a panel, and we could have all colors you’d like.”

“Yes. And they’ll be able to see us through everything.”

John invoked sets used by Stanley Kubrick, Denis’ boss on Dr. Strangelove (that film was the source of the footage used during the “Flying” sequence in Magical Mystery Tour), and the man floated to direct a version of Lord of the Rings starring the Beatles. An extensive recap of that aborted episode in Beatles history is discussed at length in Denis’ 2003 fine autobiography of his Beatles years, At The Apple’s Core.

The conversation would continue, with Denis asking someone to fetch George Djurkovic, art director of The Magic Christian, from the film’s set elsewhere at Twickenham to provide added insight. But while Paul continues to play “The Long and Winding Road” in the background the conversation on the tapes meandered to a new duo: Ringo — one of the stars of The Magic Christian — and Michael. While Denis and John spoke as if the live show was to be held at the studio, Michael continued negotiations on taking the show on the road with Ringo. They were the leaders of the rival factions: Stay-put Starr vs. the whole Hogg.

“If I do go, I think it’s better just to go for four or five days,” Ringo said, showing newfound flexibility. “We don’t need to go to rehearse.”

Ringo was willing to bend and travel, but there’s a catch: “I’d like to do it to a British audience.”

It’s a catch, but one Michael is willing to receive. “Can we all talk about it? Will you take the veto off if you can be convinced we can get an audience?” Michael asked.

A Roman amphitheater wasn’t artificial, but to Ringo, the whole reason to perform overseas was contrived. The only reason to travel was the “helicopter shot, you’ll see the sea, the theater. And that is, for one, two minutes, say, that shot isn’t worth me going down there when I really prefer to do it here.”

Two and a half months after Ringo suggested the Beatles perform before there for a “British audience,” John and Yoko would be married in Gibraltar (near Spain).

“I see us doing a good show here [at Twickenham], because it’s you [the Beatles],” Michael said, again conceding this could be the last TV program the band will ever do.

Speaking quickly, Michael continued: “Everything you do has got to be good. All your albums are good. …. It’s not only you as the band, it’s not only them as songwriters, it’s the four of you.

“It’s got to be the best.”

Of course they’re the best. Like Ringo doesn’t know that?

“Every time we do anything it’s going to be the best,” Ringo replied. “Can’t we just do something straight?”

And back to Twickenham, and staying precisely put.

“At the moment, that scaffolding set and the tubular thing, it is kind of like four years ago,” Michael said. “And there’s nothing wrong with four years ago. … We’re all 28 now, or whatever we are. The audience isn’t the same, life isn’t the same.”

For the record, John, Ringo and Michael were all 28, Paul was 26 and George a wee 25. But his point remained legitimate. This wasn’t 1965 anymore.

“This place, it could be rock and roll, ” Michael began.

“It could be rock and roll in Tahiti or wherever you want to put us. What’s it called? (laughing)”

Michael’s not even sure himself. “It’s either Tunisia or Tripoli.”

Ringo asks about a British possession likewise on the Mediterranean — “What about Gibraltar?” — before turning his attention back to the room he was in and the music, ignored during the conversation.

How’s this for an idea of stripping a show down?

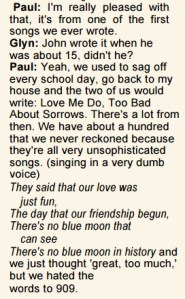

“See, Ringo said, “I’d watch an hour of just [Paul] playing the piano.”