In a time of global crisis — isn’t it always, though? — it was the world’s greatest legislative body. OK, maybe the Beatles were the world’s greatest band that also tried to behave like a legislative body, and late in the day on January 8, 1969, it was nearing time for a decisive vote on a lingering issue: Where would the Beatles play their next — and presumably last — concert?

You know his name (look up the nation)

From the band’s outset to its imminent end, the Beatles prided themselves on what they called democracy, but it was really complete consensus. “We had a democratic thing going between us, particularly by 1962,” George Harrison told the high court in 1997 amid a lawsuit to stop the release of a Beatles recording from one of their residencies in Hamburg. “Everybody in the band had to agree with everything that was done.”

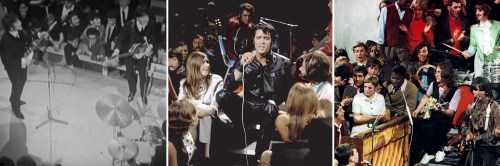

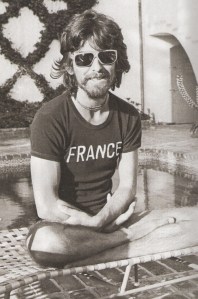

Unanimity isn’t necessary to the democratic model, but this model United Nations was extraordinary by nature of its four voting members: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. The two serious veto threats earned code names from director Michael Lindsay-Hogg — Russia (Ringo) and France (George, so named “because he smoked some garlic once,” per Paul).

Continuing his earlier conversation with Ringo, and desperate to sell a show overseas, Michael laid out the situation as he saw it in hopes of chipping through the Iron Curtain.

The way it stacks up is, John is happy to go. … Paul is, I gather, in the middle, tending toward either side … and George is swinging more your way. So there’s quite a tough battle. The problem was we couldn’t talk about it because of Russia. And it’s the four powers. And if Russia says no, then the conversation is obviously in the bag and we can’t do anything with it. And I think if we now can talk about it, we may still discard it … or we may come up with something better.

In retrospect, the drama of the group’s incapability of finding agreement on a concert location, despite the suggestion of several intriguing venues, would have made for a captivating documentary for Michael. It would have given a narrative the Let It Be film lacked. But after less than a week of sessions, the director saw things differently.

“My documentary is running out of gas,” Michael admitted to John. “If we were to vote tomorrow, it’s not running out of gas.”

Fine-tuning the group’s intentions would do more than make for better television. “It might make it better again, whatever the wound is,” Michael told John moments earlier.

“Yeah, that’s what I was thinking,” John replied.

And here you thought John didn’t care about the band anymore. The Beatles were a wounded group before the Get Back sessions started, and salt would soon be added when George quit in two days’ time. But the Beatles were still worth saving in January 1969, even if John himself would call it quits well before the calendar year was out.

The day’s musical session was complete, Paul having walked the group through “The Long and Winding Road” and “Let It Be.” For these final 15 or so minutes on the tapes, all four Beatles are engaged, animated and opinionated concurrently to a degree yet unheard to this point on the Nagra reels.

All the principals immersed, Denis O’Dell makes the sell on Michael’s repeated preferred overseas adventure.

“I really think we could go and shoot a day sequence, a night sequence, a torch-light sequence, out there the sea, desert, in four days. Make it comfortable for everybody.”

Paul’s skepticism remained. But he was willing to keep options open and the live concert plans … uh, afloat.

My major objections to that: Traveling, one. Setting up and everything — I’m sure we can do that. Then, there’s that thing, which may not seem much, but we’re doing a live show, and we’re doing it in Arabia (laughter), and everyone’s waiting to see the lads rocking again. So, like, I’ll tell you what then, I’ll come in with it as long as you can get a couple of boats, the QE2. And then give away the tickets here, as you would have done, but the ticket includes a boat journey as well.

The composition of the audience was a sticking point, especially for Ringo, and there’s something virtuous to be said for the lads’ loyalty and desire to be rocking again before an audience that was with them from the start.

“We’ve got to get the right audience for Russia,” Michael said. “If we can get the right audience over there, which we can get over there.”

George wasn’t easily swayed. “What is the point of doing it abroad… apart from getting a great holiday? I’d much rather do it and then go away.”

Reminding the band of Twickenham’s relatively pedestrian features, Denis replied, presumably waving his hand at the scene around him, “To get away from that, that’s really the answer.”

“It’s ‘Around the Beatles ‘69′,” John acknowledged after a brief exchange about potential set possibilities on the Twickenham stage.

Paul, having had enough at the end of a long day, aggressively presented a compromise.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll offer you. If we’re going away, and we hire a boat to take the audience with you, we’ll do a bloody show on the boat, and then we’ll do a show when we get there, in the moonlight. … Final dress rehearsals on the boat.”

History never stopped chasing the Beatles, and sometimes it caught up to them. They didn’t want to repeat a past accomplishment, whether it was “Around The Beatles” or a stadium show. But Paul’s suggestion would have done just that: Bringing along a select audience to a performance at sea would combine a pair of episodes from the other side of their career.

Feb. 20, 1962, just a month after Brian Epstein formally signed on to manage them, the Beatles — that’s still John, Paul, George and Pete, at this point — performed an important show at Floral Hall in Southport. From Mark Lewisohn’s epic Tune-In:

[Epstein’s] principal involvement in the Floral Hall night was two-fold: to help sell the 1200 tickets and to book the talent that would provide continuous dancing for four hours — five groups headed by POLYDOR RECORDING STARS, THE BEATLES. He circulated typed leaflets among Beatles fans and on the record counters at all three Nems shops, announcing affordable coach trips: fans could pay 8s, 6d for return transportation, admission to the hall and, afterwards, the chance to mingle with the musicians and get their autographs. These special all-in tickets were sold only in the Whitechapel shop, outside which the chartered buses would leave. The Beatles were taking a Liverpool audience with them for a night out up the coast.

Emphasis mine.

Instead of towing British passengers across the Atlantic and Mediterranean, the Beatles brought their fans from their Cavern Club base in Liverpool about 20 miles up the A565.

That was by bus. Six months before the Floral Hall show, the Beatles made the first of four appearances on the Riverboat Shuffle, a concert series on the MV Royal Iris, a ferry cruising in the River Mersey.

For Paul — who would record parts of Wings’ London Town on a boat in the Virgin Islands in May 1977 — the Royal Iris performances made enough of a lasting impact that he referenced them decades later on his 2007 LP Memory Almost Full:

The journey wasn’t as important to Michael as the destination: the Roman amphitheater in Sabratha, Libya.

“I don’t think anything is going to beat a perfect acoustic place, by the water, out of doors, a perfect theater, with perfect acoustics,” he said.

John was on board. “Just singing a number, sunset and the dawn and all that. Gentle, and the moon, and all that for the songs, you know.”

“I think we’re going to do rock and roll at dawn or at night, and we can have the change of day over something like this,” Michael replied. “Because I’m sure we can do the rock and roll there if we get the right audience.”

All-important consensus was building between the two most powerful members of the band, and it was more than wanderlust and closer to finding a way to heal that wound — do something different, but still be together as The Beatles.

“Last year, when we were doing the album, like you said, we suddenly said we don’t need to do it here, in EMI in London,” Paul said. You can listen along to this particular sequence on the “Fly on the Wall” bonus CD packed with Let It Be … Naked.

John excitedly picked up the argument.

“Every time we’ve done an album, we’ve said, ‘Why are we stuck in EMI, we could be doing it in L.A.! We could be in France! And every time we do it, and here we are again, building another bloody castle around us, and this time we [should] do it there. And not only would we be doing it, physically making the album there, but it takes [off] all that weight of, ‘Where’s the gimmick, what is it?’ God’s the gimmick. And the only problem we’ve got now is an audience, you know.”

For a moment, at least, Paul’s skepticism vanished.

“It makes it kind of an adventure, doesn’t it?”