Gazing at 20 Manchester Square in London, I squinted trying to visualize the Beatles hanging over the stairwell, flashing their grins. They did it in 1963. They did it again in 1969. What a backdrop was EMI House!

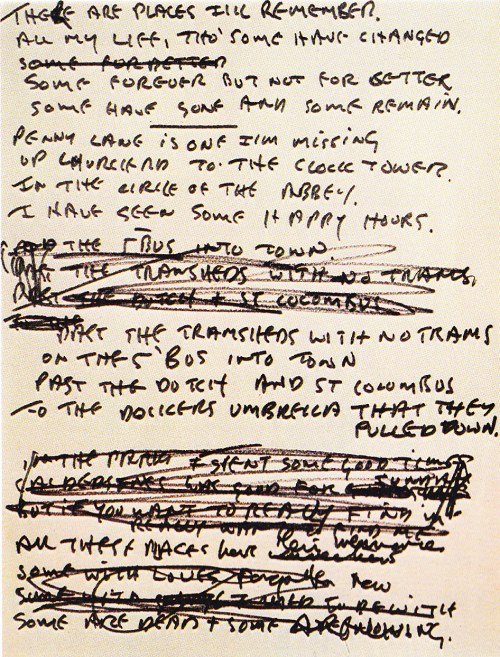

At the same time, my then-13-year-old son stared at the same building standing today at 20 Manchester Square, a structure decidedly not EMI House, which was torn down at the turn of the century.

This was his breaking point. The Mad Day Out had little on our Furious Day Out.

We had been in England nearly two weeks, and on this Wednesday morning, 20 Manchester Square was the second location we purposely visited over the previous five minutes that was purely a street name and number. The first Apple Records headquarters once stood at 95 Wigmore Street, literally in shouting distance of 20 Manchester Square, and in the place of the former Beatles HQ, another modern construction rose where a historic Beatles site once stood.

20 Manchester Square, today

“These aren’t even the buildings the Beatles went to!” he screamed at me – I was very much in shouting distance. “Why are we here? Why do even you care? It doesn’t make sense!”

And to a point, he was right, even if I wasn’t crazy about my teenager yelling at me in Marylebone. While we were in England, we visited Hadrian’s Wall, Stonehenge and the Rosetta Stone precisely because they survived centuries and millennia. The kids never asked to see the site of the Euston Arch or Crystal Palace, and I get why they didn’t.

95 Wigmore St, Apple’s first HQ (early ‘68). That building is gone; the one here was built in 2013. It’s Colliers UK’s head office.

I knew the names, and I looked up the numbers. But much as I wanted to see where the Beatles made their magic and soak in that residue, 20 Manchester Square and 95 Wigmore Street remain merely addresses on a map. Still, to paraphrase one of my favorite Liverpudlian philosophers: Some places have gone while some remain, and all of them had their moments.

***

I always planned to write about my trip to England. My family of four traveled for two weeks June 2024, mostly split between Liverpool and London and with various Beatles pilgrimages at the center of the itinerary, which included several other non-Fab (but still fabulous) destinations. I’m not convinced you want to read How I Spent My Summer Vacation, but I think I can interest you in a broader review of precisely how I did end up spending my summer vacation, even if you’re from Merseyside or the capital or know the Beatles every bit as much as I think I do.

Yes, I bought several cans of Let It Bean.

Yes, I bought several cans of Let It Bean.This is a result of some deep reflection, and will be part-essay, part-travelogue and complete expression of child-like wonder at how exciting it was to step in the Beatles’ footsteps and unlock an understanding of who and what they were and are and why that matters to me.

The trip was special. I gazed at the rooftop and stood by the basement. I crossed the road. The lane was in my ears and in my eyes. There was so much more.

I was very fortunate. I shared a few hours with a man who was on that rooftop. I spent time alone in a very different, but more formative basement. I visited a lot of places that had their moments, and a lot of locations that once did – but really always will, even just as addresses on a map.

I’m not going to tell this story chronologically. How I planned my trip really only mattered to my schedule and ultimately doesn’t matter. This should read as an evergreen story, as we say in the business. But hopefully there’s a tip or two in here if you’re planning your own journey. Extroverted as I am, I hate writing about myself, but without it, this won’t be much of a story.

***

The most striking thing about being in the Beatles’ England was how it felt mundane, in so many ways. At once, I appreciated them and their music much more deeply, although at the same time recognizing I didn’t need to be there to understand that.

I wasn’t expecting grandeur, necessarily, though as I write this out, maybe I was? The Beatles are on that historically vital level. Buckingham Palace, Salisbury Cathedral — these are larger than life destinations I admired in person. So what does that make Mendips or 34 Montague Square? The Beatles certainly mean more to me than the monarchy and Anglican Church.

At the beautiful Chapter House at Salisbury Cathedral (where one of the Magna Carta originals is housed), decorative cushions ring the perimeter, and I was able to compile one variant of the set.

It’s one thing to view, say, John Lennon’s Epiphone Casino behind glass at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland (which I’ve done multiple times!). It’s another to see the rooftop, basement and front door of 3 Savile Row as part of its surrounding environment. There it stands between other buildings that have their own rooftops, basements and front doors, too.

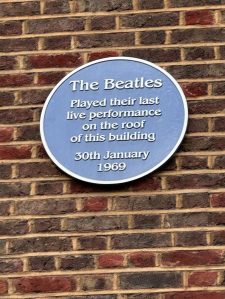

The Rosetta Stone stands behind glass at the crowded British Museum, while about a mile away, 3 Savile Row — as important as it is — does not. We have to already know it’s special, blue plaque notwithstanding.

***

It’s really hard to change a first impression. Liverpool long cast to my aging eyes in black and white, its sounds blared in mono. That’s the Beatles’ Liverpool I’ve always known from photographs and films.

The city as viewed (by me) from the Wheel of Liverpool

Personal experience broke that bias. I found the city – our first stop on the trip — lively and electric, full of the color missing in my expectations. It’s not an exaggeration when I say it was a spiritual experience to walk the streets and follow in the footsteps of the Beatles.

Mathew Street, Liverpool

So full of magic, one of Liverpool’s incredible tricks is to effortlessly convince you of something Apple has subtly promoted for years, most recently with the “Now and Then” experience: The Beatles never really split. This is the city of John, Paul, George and Ringo. And Pete. And Stu! Brian Epstein lives. It’s Mathew Street stuffing decades of history over just a tenth of a mile. It’s at once authentic, reconstructed and behind glass.

The Brian Epstein statue is just footsteps away from the former location of NEMS.

The Beatles’ entire origin story happened in Liverpool: childhood, crossing paths, forming a band and superstardom. You can retrace their origins to the depth of your own desire and timetable.

My favorite Mathew Street location was the Liverpool Beatles Museum, which carries a breathtaking, unique collection. It’s a must-visit if you’re visiting Liverpool.

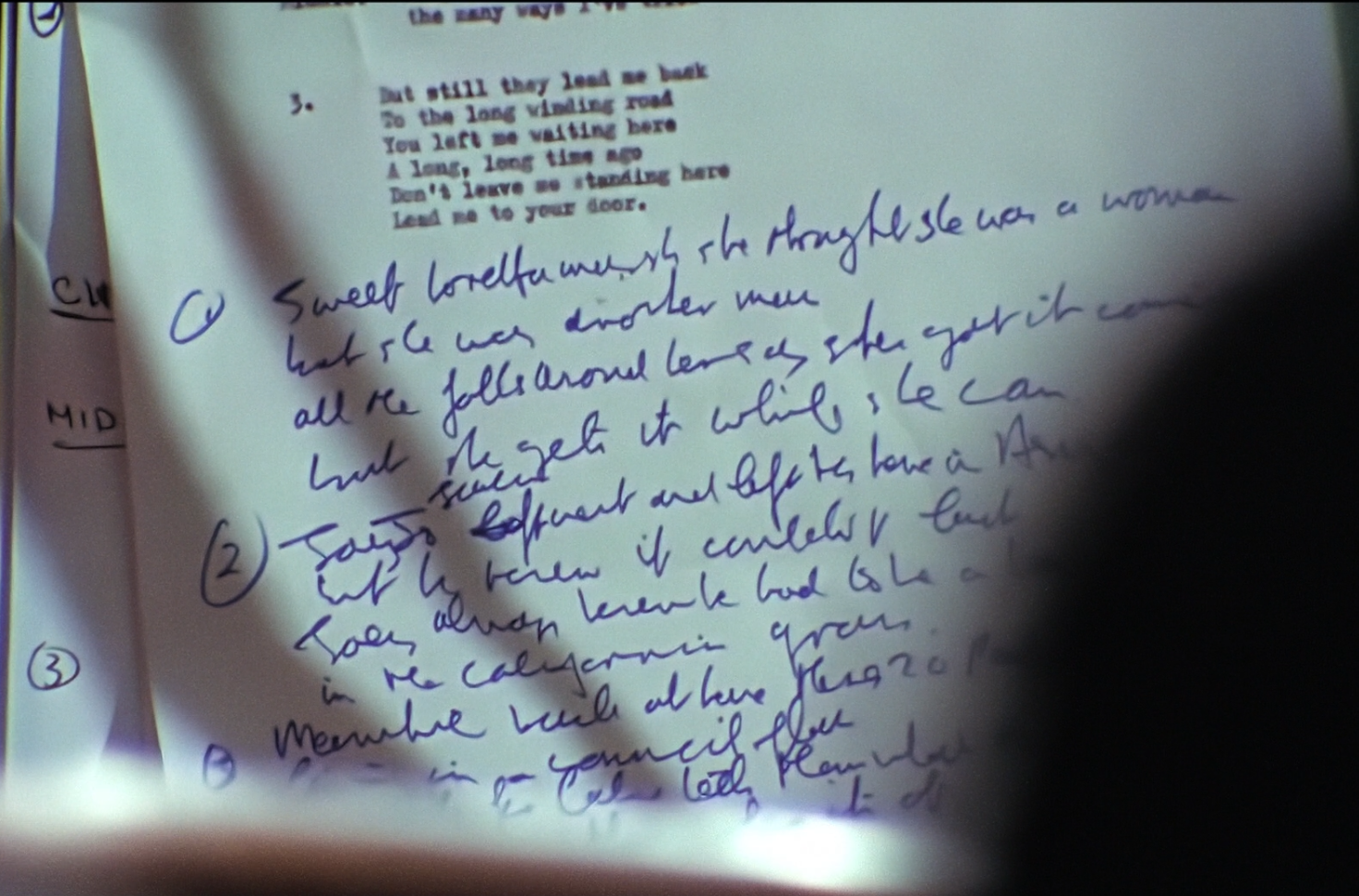

- As displayed at the Liverpool Beatles Museum.

The National Trust conducts tours of John and Paul’s childhood homes only in conjunction. While not the same route they would have taken in their day, we were bussed between the two houses. The Lennon/McCartney partnership, forged when they called these places home, lives in perpetuity as a combined experience.

“It was important then whether you lived near each other or not,” Paul recalled in the Anthology book. “There were no cars for kids in those days.”

Our first stop on the Lennon-McCartney house tour was John’s childhood home at 251 Menlove Ave. Despite Mike McCartney growing up on Forthlin, it was Mendips that was enveloped in scaffold.

I found no light bulb on visiting the childhood homes of, oh, the way this room is laid out is why Paul learned to play things this way. Or John became that way because of the kitchen. The acoustics in the McCartney bathroom, as good as they may have been, didn’t create Lennon-McCartney.

However that magic manifests itself, though, it lingers.

We played Paul’s piano. No, not his childhood piano – that’s now at one of his own homes. But it’s a piano played by Paul, and that’s good enough for me. Who cares when he played it?

20 Forthlin Road

By their natures as simple residences, the Lennon-McCartney homes stood among the more pedestrian destinations, even with some things behind glass: The spot where Paul slept (though probably not his original bed). The room where John ate (though probably not the table).

12 Arnold Grove

Privately owned, George’s and Ringo’s childhood homes were only street-level photo-ops, but just experiencing these neighborhoods added depth to their stories. Seeing the Empress Pub step out of the Sentimental Journey LP cover only a few footsteps away from 10 Admiral Grove in the Dingle was added value.

The Casbah Club is very much alive, with Pete Best and his family literally welcoming you into his childhood home. We visited a couple months too early to stay there (it opened as an Airbnb in August 2024). It’s in the Casbah’s basement that the colors of Liverpool perhaps glow most bright, the paint jobs of the Quarrymen (plus the future Cynthia Lennon) still adorning the walls and star-studded and Beatle-etched ceilings. The club area and the spaces where the Quarrymen and Beatles played stand claustrophobically small when you allow yourself to visualize the crowded houses they played for. Mona Best’s incredible legacy looms and lives strongly.

The remarkable Casbah Coffee Club. What a destination! Thanks to Roag Best Jr. for the fab tour inside.

But beyond the artifacts Beatles once handled and spaces they occupied, the locations they chose to be inspired by made their mark.

Like both sides of the greatest single in pop music history. We visited Penny Lane and Strawberry Field consecutively, with Paul’s contribution our first needle-drop.

Your host at Penny Lane. Squint close and you’ll see Paul’s signature on the sign. Also, gaze upon the shelter in the middle of the roundabout, the one-time bank and the barbershop.

The magic of “Penny Lane” speaks in that the song doesn’t have to be taken as personal at all. It’s observational, and we can see the same surface elements today. The barbershop, the (former) bank building, the roundabout’s shelter – these are tangible, ordinary locations like ones I have in my own town, and every one I’ve ever lived in. We don’t really need to know the motivations of the banker or firefighter or nurse to really understand the song, which still creates a relatable story.

No wonder “Strawberry Fields Forever” made such a natural flip side, it really was the opposite experience, even today as Strawberry Field itself remans a functioning Salvation Army facility that’s also a popular tourist destination. You can still experience the quiet isolation John sought, and find your own tree after a wander in the garden.

Let me take you down ’cause I’m going to Strawberry Field.

Rather than demystify these destinations, walking through I found them enhanced, spotlighting the proximity of the Beatles’ world. Strawberry Field sits so close to Mendips. And then seeing the central terminus that’s Penny Lane plus John and Paul’s childhood houses in the same short afternoon — on a long tour as led by Dave Bedford, bursting with of endless insight and access – it was beyond expectations.

Penny Lane and Strawberry Field weren’t just name checks. These places mattered to the Beatles, but being there put it in such a better context. It’s something they evoked themselves, and they tried to give us an idea to the context on the single’s sleeve and promotional materials (depending on the country).

As seen in Cashbox in February 1967.

“A lot of our formative years were spent walking around those places,” Paul said in Anthology. “Penny Lane was the depot I had to change buses at to get from my house to John’s and to a lot of my friends. It was a big bus terminal which we all knew very well.”

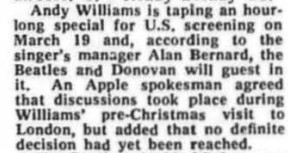

Penny Lane mattered enough to John as a location to originally appear in the the draft lyrics to “In My Life,” along with several other locations.

In his 1980 interview with David Sheff, John recalled how a basic rollcall of locations didn’t work.

‘In My Life’ started out as a bus journey from my house at 250 Menlove Avenue to town, mentioning every place I could remember. I wrote it all down and it was ridiculous. This is before even ‘Penny Lane’ was written and I had Penny Lane, Strawberry Fields, Tram Sheds — Tram Sheds are the depot just outside of Penny Lane — and it was the most boring sort of ‘What I Did On My Holiday’s Bus Trip’ song and it wasn’t working at all. I cannot do this! I cannot do this!

But then I laid back and these lyrics started coming to me about the places I remember. Now Paul helped with the middle-eight melody. The whole lyrics were already written before Paul had even heard it. In ‘In My Life,’ his contribution melodically was the harmony and the middle eight itself.

“Ordinary” Beatles should not have been a surprise to me. I study the Nagra tapes the most of anything Beatles, and that is them at (what I always assumed) was their most mundane — talking about TV, food, the news and anything else. I find ordinary Beatles to be extraordinary Beatles.

Want to know why I believe John when he said “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” was based after a drawing by Julian and not LSD? Because of the ordinary things they wrote about otherwise.

So much of the Beatles has to do with their time. I couldn’t turn back the clock, but I could get to their place.

Like St. Peter’s in Woolton. It’s the Church of the Immaculate Conception, at least when it comes to the Beatles. Your own bias will say whether this is where Paul met John or John met Paul. Lucky us, the doors to the church hall were unlocked (maybe they always are, I don’t know!) and we stood in the very spot – at least our best guess within a few feet – of the Big Bang.

St. Peter’s

Strip away the origin story, and it’s today a rec room sincerely not unlike any other at this kind of church community building. Here children’s Sunday School scrawls are given equal status to placards documenting the fête-ful encounter in 1957. This could be a room in any one of our hometowns.

Outside the building at the church’s cemetery was one more bit of inspiration, even if the Beatles didn’t realize it deliberately. RIP Eleanor Rigby.

“I don’t remember seeing the grave there, but I suppose I might have registered it subconsciously.” Paul wrote in Lyrics. “We visited her grave in a much more deliberate fashion.”

***

What Liverpool enjoyed and embraced but London lacked is a broad Beatle presence. This wasn’t a surprise, but was certainly tangible after spending time in Liverpool. It’s a big city. I get it, I’m from New York. There’s a lot going on.

I’d been to London before, as a teenager in the 1980s. I had a lot of places I wanted to see myself this time around, with one obvious destination circled several times.

Myself at 14, crossing you-know-where. It was 1989, but I’m not sure when my fashion sense was from.

Myself at 14, crossing you-know-where. It was 1989, but I’m not sure when my fashion sense was from.I’ve been writing about the Get Back sessions since January 2012, a long while after Let It Be hit theaters (May 1970), and a quite a bit before Peter Jackson’s Get Back revitalized the sessions into the mainstream (November 2021). My visit to 3 Savile Row – the centerpiece of our busy London visit — was a powerful moment to become a 21st century Apple Scruff and linger outside the building; there was no entry.

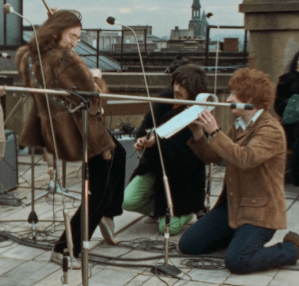

I wasn’t waiting for anyone to arrive or depart, but simply loitering delivered a unique satisfaction. This went beyond the rooftop performance. And that in and of itself was very powerful. The roof didn’t feel as high as it appeared in Let It Be and Get Back. Really, it felt short. It was five stories, like other buildings on the same block and any other five-story buildings in my hometown or anywhere else. I know the Beatles played a concert on that particular one.

The Apple of my eye: 3 Savile Row

And obviously that’s what made it a powerful moment. I was very surprised – like I was at so many Beatles-related destinations – at how few people were there to pay tribute. I visited around 1 p.m. on a Wednesday (the Beatles played at around the same time on a Thursday). Unlike January 1969, Savile Row was very quiet this afternoon in June 2024.

There was a small tour group listening to a stock spiel about the Beatles and the rooftop. If anyone around needed to know the building was special, they could have looked at my idiot self photographing it from all angles, peering into the basement, dodging back and forth across the narrow road – it wasn’t much wider than Mathew Street – and rubbing the metal No. 3 bolted to the front door as I insisted I could absorb the building’s mojo and mystically ascend to the road that stretches out ahead. I made sure to inhale whatever Beatle dust lingered.

The proximity was interesting: The Heddon Street location where David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust LP cover was shot pretty much stands around the corner from Savile Row. From there it was a 10-minute walk to the former location of Trident Studios, where not only Bowie made his mark, but the Beatles cut “Hey Jude,” “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” and a few others. Depressingly it looked like an office today. I could see a printer, but no piano. But that obscures the point: Everything was right there.

The same day we made it to St. John’s Wood — and it was a day, spanning more than 15 miles by foot alone — we did the least surprising thing possible and lined up to cross Abbey Road. It should have occurred to me before but I never thought about it: It was only as I crossed the road that I realized I was – in the Beatles’ footsteps – walking away from the studio. (But they all left together, at least.)

Of every Beatles-related location I visited over two weeks – and there were many – only the rebuilt Cavern rivaled Abbey Road for walk-up crowds. We fans had each other’s backs, gladly offering to take pictures for strangers so we all could have that killer crosswalk photo.

A kind Australian nailed for posterity my family’s crossing in two takes. The reckless New Yorker I am, I giddily stood in the middle of the street, forcing traffic to dodge me – not the other way around – taking photos to make sure a couple from Los Angeles had the perfect picture. It took four takes, and I would have done a fifth. Iain MacMillan I’m not, but I tried.

Abbey Road

Paul famously lived just down the road, and we recreated the quick walk to Cavendish, surprising ourselves at just how close Paul lived to EMI Studios on Abbey Road (not even half a mile).

The home today didn’t seem much different than description in Hunter Davies’ biography of the band, published in 1968:

The front of the house has a paved courtyard with an old-fashioned lamp-post. On the left, attached to the house, is a double garage in which he keeps his Mini Cooper and Aston Martin. The house is guarded by a high brick wall and large double black gates controlled from the house. You speak into a microphone, someone inside answers, and if you say the right thing, the doors swing open and then clank shut again to keep out the fans.

I did talk like an absolute maniac at his security system, but I wasn’t surprised the gates did not swing open. We were the only fans on Cavendish. And this was helpful to give the space to consider things and experience the proximity like the band did – I tried to do this at every destination. We considered crashing Billy Fury’s old place, which was just a few houses down, when the door opened to welcome guests in.

London’s Cavendish Avenue, featuring the homes of Liverpool’s Paul McCartney and Billy Fury

It wasn’t deliberately scheduled this way, but Abbey Road and Cavendish were the last two main Beatles-related destinations on our trip (we left England a couple days later). They were also two of the remaining locations that were as they were when it was the Beatles’ England in their time. Music continues to be recorded at Abbey Road, and Paul still has the keys to Cavendish today.

***

I walked in the footsteps of the Beatles on Abbey Road and rubbed the door at 3 Savile Row for the best of luck. But can a place really leave magic? Do people leave some of their essence? I thought about this a lot when I was in Liverpool, and again when we got to London, especially in Mayfair. When my teenager lost it outside the former EMI House, our next destination was the fascinating Handel Hendrix House.

George Frideric Handel called 25 Brook Street home from 1723 until his death in 1759, composing “Messiah,” “Water Music” and many other lasting pieces in that building, where his legacy is lovingly preserved. I’m no Handelhead, but the site was terrific.

The other half of the Handel Hendrix House is named for James Marshall Hendrix – you know him as “Jimi” – who lived at the adjacent 23 Brook Street more than 200 years later.

Handel, with care: The Handel Hendrix House was a definite highlight among Beatle-adjacent destinations

“I didn’t even know this was [Handel’s] pad, man, until after I got in,” Hendrix told the Daily Mirror on January 6, 1969, in an interview published five days later. “And to tell you the God’s honest truth I haven’t heard much of the fella’s stuff. But I dig a bit of Bach now and again.”

Handel wasn’t any kind of musical inspiration on Hendrix, so if the composer left any juice for Jimi, we can only guess — although Jimi did reveal he once saw “an old guy in a nightshirt and gray pigtail” walk through a wall.

When Jimi moved in, it wasn’t even the most historically significant thing that happened in Greater London rock history that day. Because on January 2, 1969, as Jimi Hendrix schlepped his guitars and other belongings up the stairs into his new pad – it was actually his girlfriend’s apartment — the Beatles began the Get Back sessions 10 miles away in Twickenham. So is there magic in a time, and also a place?

***

While I could approach some places, I could never get to the Beatles’ time. But I could spend moments in my own time with someone who was in the Beatles’ circle.

Milton Keynes wasn’t out of the way as we drove from Stoke-On-Trent, the base for our visit to the amusement park Alton Towers, toward London. Paul McCartney adopted sweet pup Martha in Milton Keynes, and dog-lover I am, that’s reason enough to give the town a nod. But I’d be lying if I said it was on our original itinerary.

On a trip filed with journeys to places that mattered, at this vacation’s heart was one destination that didn’t matter at all – it was the person there that gave it meaning. This moment was right in the middle of the trip, between our Liverpool and London legs.

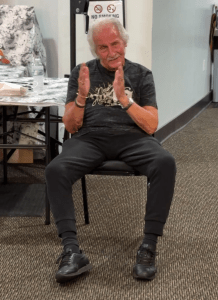

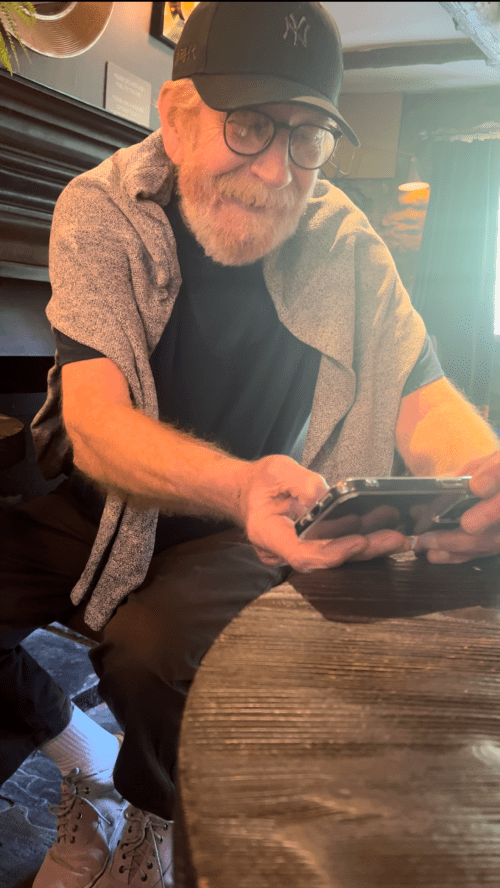

All thanks go to Robert Rodriguez, who you know as the host of the Something About the Beatles podcast and author of several books (buy his newest one now!). He’s also a kind human being who incredibly connected me with someone who was in the middle of it all: Kevin Harrington, former Beatles equipment manager. If you know him for nothing else, you’d recognize him as the young redhead on the rooftop and throughout Get Back/Let It Be.

Our man Kevin Harrington holding court in Milton Keynes.

Kevin spent what he called “three, four years out of a long life” working for Brian Epstein and later the Beatles. We spent about 2 ½ hours at a pub in Milton Keynes. He said it wasn’t his local, and that set the tone for the conversation – he felt he could speak with candor. This wasn’t an interview, but a conversation. I asked about his time working with Tina Turner, Motörhead and Kid Creole and the Coconuts. We talked about instant replay in sports, navigating roundabouts and his recipe for herb sausage.

John, George and Kevin on the roof, January 30, 1969.

Obviously, we talked most about those three, four years with the Beatles and the incredible cast of characters that surrounded (and included) him. It was clear there were some “pub stories” not meant for broadcast, and I will hold them near and dear.

In a remarkable happenstance, not even 48 hours before we met, the Lennon Estate released the promo video for “You Are Here” as part of the Mind Games reissue campaign. One of the first recognizable heads in the clip is Kevin Harrington. The very existence of the video – which is drawn from John’s 1968 exhibition of the same name — was news to him.

In a very big life filled with outsized experiences, Kevin watched himself, on my 6.1-inch phone screen, hauling a giant, round canvas down a London street nearly 56 year earlier, during a weekend in the midst of the White Album sessions.

Kevin named every face he remembered as they were shown on screen, a roll call bringing true flesh to the conversation. It was one of those moments when cardiologists be damned, I blindly allowed my heart to skip a few beats.

Wherever he was, he was there: Kevin watches John’s “You Are Here” video for the first time

Going into our afternoon together, I knew how Kevin would approach this sort of meeting. From his 2015 memoir “Who’s The Redhead On The Roof….?”:

The time line is a bit hazy. Do I wish to look up all that happened in those far off days to check dates and so on? Honestly no, I don’t. I’ll leave that to the experts. Maybe if we meet one day you can tell me exactly what I was doing, when and where. I can only tell you what it was like for an 18 year old to work for the biggest band in the world.

Kevin wasn’t a docent speaking from a memorized script. When he talked about John Lennon or Derek Taylor or Mal Evans or former boss Brian Epstein — who more than a half-century later he still referred to formally as Mr. Epstein, just like the Beatles would — those were memories. There’s something to speaking to a person that’s so much more fulfilling than to going to a place or searching for a time.

***

It’s deep into spring now, after a long, cold, lonely winter. I couldn’t get myself motivated to finish this piece. I love to write, and I love to write about the Beatles. Yet, here I am, more than 4,000 words in and not sure if I had anything to say.

In true Get Back/Let It Be fashion, this unfinished mess of words (in my case) sat shelved. I’ve reworked and revised, and I’m still not sure I like any of the finished product. Scraps of unrealized points, salient and otherwise, lay saved in text files, waiting for an eventual bootleg leak.

There’s no Glyn Johns or Phil Spector to bail me out. And where is the ending? To put it in John’s words, I’m afraid “it was the most boring sort of ‘What I Did On My Holiday’s Bus Trip’ song and it wasn’t working at all. I cannot do this! I cannot do this!”

A few weeks after the trip, I saw Pete Best perform live at a venue just 15 minutes from my own home in Ohio (more in the last post about our interaction). I didn’t have to travel across the world to be in a Beatle’s world.

- Pete Best in Kent, Ohio, in July 2024.

Pete Best (and my family) in Kent, Ohio, July 2024

But that’s not an ending, just an epilogue.

Our trip ended quietly. A week after seeing Kevin in Milton Keynes and on the heels of nearly a week in London, we flew out of Heathrow and returned home. The night before our flight, I had to run out to fill our rental car. We were staying in Slough, which I know best from The Office, but it also was once home to the former Adelphi Cinema. One of the Beatles’ performances there was the night after their iconic 1963 Royal Variety Show performance, which prompted this exchange between Paul and the Queen:

“The Queen Mother said, ‘Where are you playing tomorrow night?’ I said, ‘Slough.’ And she said, ‘Oh, that’s just near us.’”

Bonus Beatles site! We fly out early tomorrow to come home, but I snuck in one more place, the site of the former Adelphi Cinema in Slough, where the Beatles played twice. Today, it’s undergoing renovation as a banquet hall. (As in, people were there working at 8pm on a Friday) pic.twitter.com/IqRA8X13Xg

— They May Be Parted (@TheyMayBeParted) June 14, 2024

I didn’t even have to go out of my way to see the former venue, driving right by it on the way to the petrol station. The ex-Adelphi was another address on a map, a building under reconstruction literally before my eyes. One of the running themes took us to the very last stop.

It’s OK for things to change. The Beatles switched drummers. John gave “In My Life” a rewrite – he made it less a travelogue and much more personal. I found inspiration in that.

I would have rather seen 3 Savile Row’s windows dressed in daffodils and the basement door surrounded by Scruffs than its current state, and I wish the original Apple HQ at 34 Montague Square was there to be gazed upon. But it’s just not reality.

- Then …

- and now

I lived in two different houses over the course of my childhood. Both have since been torn down. They’re only addresses now, but I don’t need the buildings to have the memories of the people and things that went before.

There’s a magic in a time and a magic in a place. Most of all, the magic is in the people. Huw Spink – you know him as Teatles — guided me around his Liverpool, centered in particular around beautiful and essential Sefton Park, just hours after I arrived in the city. This set the tone for just how great this trip would be. We talked Beatles, we talked friends and family. We had tea.

Paul Abbott – you know him as half of The Big Beatles and 60s Sort Out podcast – showed me his Liverpool shortly before we left Liverpool. It reinforced how lovely the people, transplants or not, are. We talked Beatles, we talked friends and family. We had beer(s).

- Checking off a true bucket-list item: Tea with Teatles

- Deeply gratified at Big Sort Paul’s mini-tour of his local Liverpool

These places didn’t mean anything without the people. Whether it was our AirBnB hosts in Liverpool who gifted us a Beatles T-shirt in our unit simply because they knew that’s why we were in town or Kevin and his incredible generosity with his time.

It reinforced so much of what this trip exposed to me.

Places can be ordinary. And times aren’t special in isolation. It’s the people at those places and living in those times that make them worth returning to, something I think that’s easy to lose sight of.

The Beatles unlocked the magic of these places in their own time with the people they surrounded themselves with. Now, these locations are inseparable from the people and my own time, like Kevin Harrington and Milton Keynes last summer.

That’s why it’s just another front parlour on Forthlin Road if Paul didn’t write songs in it. No one, I think, would talk about a particular tree at Strawberry Field if it wasn’t John’s.

For me, it’s my wife loving life on the Steeplechase and Valhalla at Blackpool Pleasure Beach, my youngest enjoying baseball at London Stadium.

And it’s my oldest at 20 Manchester Square, no matter what is standing there today.