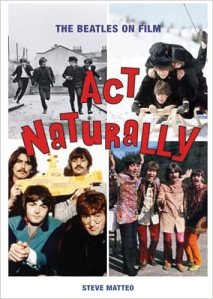

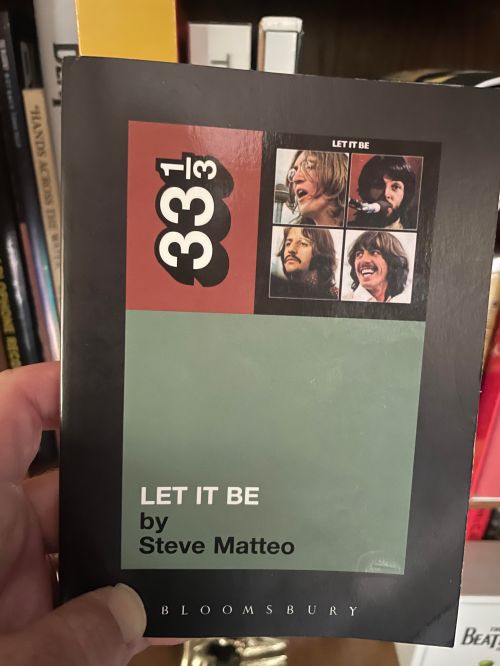

I recently had the pleasure of chatting with author Steve Matteo, who not only is a fellow New Yorker, but even better, also shares the unique experience of writing at length about the Let It Be/Get Back sessions. You may have already read his 33 1/3 on “Let It Be,” and now his latest book — Act Naturally: The Beatles on Film — takes on the entirety of the group’s core movies in heightened detail with expansive context enveloping the period. If 33 1/3 was an LP, this book is a deluxe box set.

I recently had the pleasure of chatting with author Steve Matteo, who not only is a fellow New Yorker, but even better, also shares the unique experience of writing at length about the Let It Be/Get Back sessions. You may have already read his 33 1/3 on “Let It Be,” and now his latest book — Act Naturally: The Beatles on Film — takes on the entirety of the group’s core movies in heightened detail with expansive context enveloping the period. If 33 1/3 was an LP, this book is a deluxe box set.

We spoke for almost 90 minutes, which was a great experience in real time — I suggest talking about the Beatles with people for hours, it’s always a wonderfully rewarding experience — but delivering a full transcript would cause severe eye strain. And I’m not going to start podcasting, despite my standout overnight freeform college radio stint almost 30 years ago.

So I did a little bit of both, transcribing the best bits of the conversation and then dropping extended soundbites when you want to hear a little more.

A caveat as you dig in with the hope you dig it: I’m neither a broadcaster nor professional podcaster (although I’ve appeared on several as a guest!). I recorded the audio by putting poor Steve on speakerphone and then taping the interview from a mic on a computer. I cough some. Dogs mournfully bark for treats in the distance. The conversation wasn’t originally meant to be heard, but I ultimately believed smaller soundbites would be an effective way to present further parts of the interview, even if it wasn’t properly produced.

One other minor note: We talked a little about the potential of a future “Let It Be” reissue. This conversation was held a few weeks before we starting hearing rumors of a late 2023/early 2024 re-release of the film.

The Beatles, literally, at the movies

They May Be Parted: Why did films appeal to the Beatles? Was it just general desire for fame and exposure? There was nothing their earlier biographies to suggest otherwise. They were performers but not necessarily people who dreamt of acting. Was it just a product of the time and their own love of films that drew them in?

Steve Matteo: One, let’s make some money. They’re still young kids who grew up in Liverpool and had nothing. I think it was part of just the way it was done. When you became popular and you became big in the pop music world, like Elvis and Cliff Richard, you made a movie.

And I also think that they just loved movies, especially American movies. I think that movies had always been an escape for people who are middle class or lower-middle class, where you can go, there was a time you can literally spend your 10 cents and go into these big, beautiful movie palaces and escape into this other world. And if you’re young kids in Liverpool that lived in this place that in this country was literally bombed during World War II and you’re lucky to be alive and you have no money and you have really nothing, to go into these beautiful movie theaters and see these incredible American, mostly American films of cowboys and Indians.

And, you know, Ringo loved Westerns. So it’s like a fantasy. Like you’re this kid watching these movies. You never thought you would become a movie star. You never thought you would be in a movie. That’s why the title of the book comes from that particular song (“Act Naturally”). It works so perfectly.

So there’s all of these reasons. I think once they did “A Hard Day’s Night” though, I think they kind of felt like once the train of “Help!” had started up, they were sort of like, “Oh, now we’re going to do this again.”

You know how they were, they didn’t want to repeat themselves. I think after “Help!” they were sort of like, “Well, we’re not going to make movies like that anymore.”

Listen for more

“Paul saw the potential for creativity and it was like, ‘Well, let’s try this. We’re the Beatles. We can do anything.’”

TMBP: Your book spends a great deal of space on films that predated and were contemporaries of the Beatles’ movies. How intimate were you with these films previously? Did you think, “I know the context around the Beatles films, so I want to include that?” Or, “I’m writing about the Beatles films so I need to learn this context?”

SM: I think I knew a lot about the Beatles films, but there’s always more to discover. I’ve always really loved the British films of the ’60s. I’m a big fan of spy movies, and it’s a very rich period. There was a lot that I knew, but then obviously once you start doing research, there’s so much more that you learn about. So I just felt like I didn’t want to write a book that was, “OK, the Beatles made ‘A Hard Day’s Night.’ Oh, OK, and then they did ‘Help!'” And I wanted there to be context. I wanted there to be connective tissue.

It’s like the Beatles sort of influenced everything in that period, but they were also influenced by what was going on. So it is a film book. And when you write a book on the Beatles, you want to figure out a way to have it be somewhat different because there’s so many of them. So I felt like all of this context would kind of be a way to do that. And I think it became more than I thought it was going to be.

And there’s obviously, there’s musical context too. I give a lot of what’s going on, the British Invasion, the British music that came later, the psychedelic music. And I included the San Francisco sound and the psychedelic culture and all that was going on with mod fashions and photography. And it’s like a sort of cultural history of the ’60s where the sort of jumping-off point is the Beatles films. But then I give you all this other stuff.

“I hope that really hardcore Beatle people will appreciate the book … but I didn’t want to just write a book for the fans, or a book that was just for people who are only into the hardcore.”

TMBP: With hindsight we get it, but what did United Artists see in these guys to sign them for three films in 1963? You wrote it was for a quickie B-movie kind of thing, but the group had just a couple hit songs in the UK and no American footprint at all at the time. And UA took this incredible leap of faith.

SM: I think what they really were signing on for first was the soundtrack album. Capitol had this horrible contract where they did not have the rights to a soundtrack. And so United Artists, who had a really strong soundtrack component to their media company knew Capitol doesn’t have the U.S. rights to a soundtrack. “We got to sign these guys up. They’re selling records, and we’ll make money just on the soundtrack. And if we break even on the movie, it’s fine. It’s a cheap, old movie. It’s not going to cost us a lot of money.”

“They were one of the first United States artistic media companies that were formed by the creative people. … United Artists is really important to this story”

TMBP: There’s no question to the Beatles’ brilliance, but — whether it’s the serious Beatles fan, a Beatles scholar, music writers – do we almost give the band too much credit for inventing things out of whole cloth, instead of crediting them for synthesizing and improving upon their influences and contemporaries?

SM: That’s why I wrote it the way I did, because I wanted people to realize, for example, how important Richard Lester is. How important the other people who worked on the films — the cinematographers, the camera people, the writers, all of these folks.

“You do it because you love the Beatles, and there’s a lot of love that’s going on here. I try to be a journalist, though, too, and I want to be objective.”

TMBP: Researching the Beatles is a minefield, going through 10 years worth of the band’s history that’s more than 60 years removed.

SM: And that’s why I like to use books as a source of more than newspaper articles, because newspaper articles, it’s where they say journalism is the first draft of history. The newspaper articles often get it wrong because they’re rushing to hit a deadline. And it’s written by people who don’t know pop music. And it’s, “Oh, this is going to happen.” When you read about “Let It Be,” and you read about what was being said in Beatles Monthly or those things, they’re just talking about what it’s going to be. And as you know, this is your area, it constantly changed what it was going to be and what it eventually became.

That section in particular, I felt like whatever was sort of contemporary material is it’s just filled with conjecture on what the Beatles thought it was going to be. And you know, Derek Taylor’s saying whatever. And it’s not anybody lying. It’s just, well, on January 4th, it’s going to be X. By January 10th, it’s going to be something different. So books, I like to use more as a source because they’re after the fact. Here it is. This is what happened. It’s written down here, you know.

And I try to like, you know, and I go, as you know, I go deep into explaining my sourcing. I felt it was important to do. It is a minefield. And I really worry. And then the thing that drives you the most crazy is you read sources that are supposed to be the definitive, authorized, correct sources. And those people get it wrong. Humans make mistakes, and facts that are not facts get picked up over and over again where they become gospel.

There was one fact alone, when John and Yoko met with Klein, I could not get, we’re literally talking about not even 24 hours. I could not nail that down. I contacted Chip Madinger. He was great. He’s like, “Here you go, Steve.”

People are going to just read that one sentence in a 350-page book. I must’ve spent three days on that. Just that one sentence, literally. But it has to be right. I mean, if we’re writing history, we’re writing history, we’re not writing an opinion piece. And I’m a journalist. I’m not a music critic. I’m not writing Revolution In the Head.

TMBP: The Get Back sessions are always justifiably referred to as having no set plan. They’re making up everything as they go along. In reading your book, it seemed like there was a lot of making things up as they go along in “Magical Mystery Tour,” in “Yellow Submarine.” They were written on the fly, too. It almost seems like this is just the way they like to work.

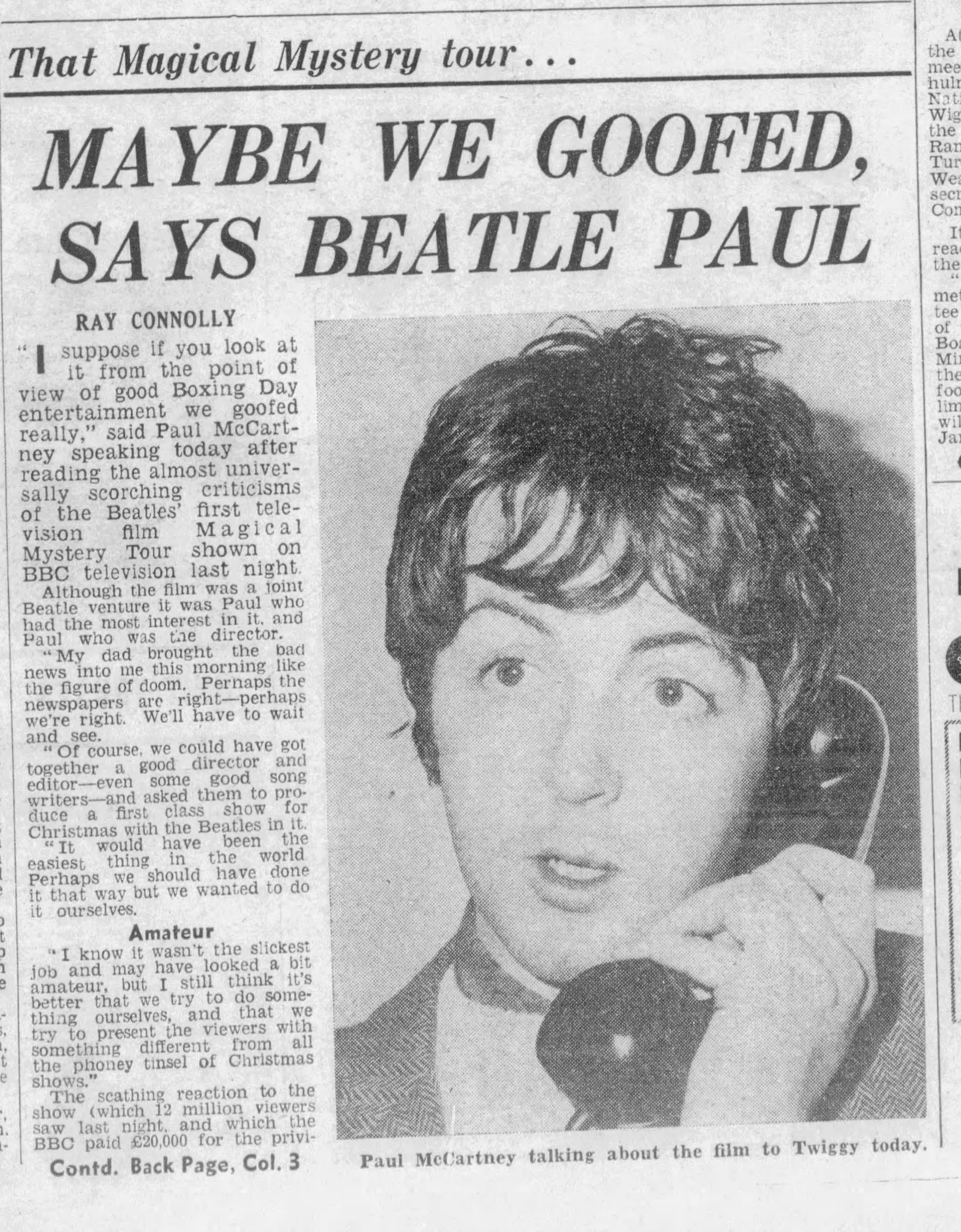

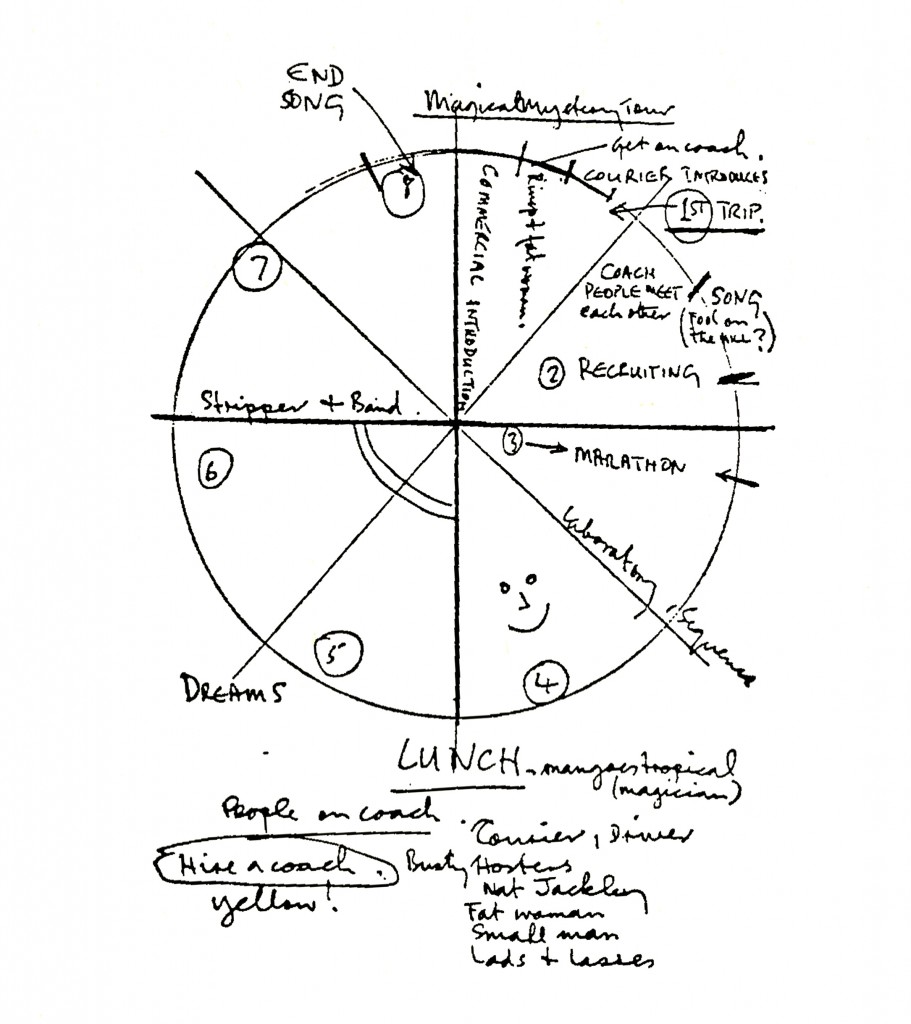

Honey pie (chart): Paul’s “Magical Mystery Tour” breakdown

SM: With “Magical Mystery Tour” they had a blueprint. They had like an outline, as you know, the pie chart that Paul came up with. And then with “Let It Be,” it’s reality TV. It’s just like, “So we’re going to set up here, you guys turn the cameras on.” I mean, that’s really what it was. So that’s a documentary.

I don’t know if you’ve read my “Let It Be” book.

TMBP: I literally have it in my hand because I have a follow-up question about it.

SM: What I did was when I wrote that, I said, “OK, ‘Let It Be,’ it was a documentary.” So I think that’s my approach. I like the journalistic approach because first of all, I don’t think anybody cares about my opinion. And I would rather present the facts and let people come to their own conclusions. There are some people that they don’t like that. They find it a little dry. They feel like it’s just that you’re stringing a lot of facts together. I try to create a certain amount of, I have my opinions here and there, and I make observations. And obviously there’s, particularly with this [new] book, there’s a ton of context. So I just think that that’s what it is. It’s a documentary. I mean, you’re not going to script a documentary. You know what I mean?

So, of course, they would rather work sort of extemporaneously. I mean, that’s what they did when they wrote songs. That’s what they did in the studio. They would say, “Let’s try this. Let’s try that. Oh, let’s go down that road.”

One of the reasons why the music is so great is because they didn’t sit around thinking too much like, “But they’re not going to play that on the radio.” And, “Well, we’re only going to sell a million copies if we do it that way instead of 5 million.”

They were these geniuses. You had these great songwriters and that’s kind of where it starts. You’ve got these songs and you’ve got this great supporting cast in the studio. You’ve got George Martin and these great engineers. And yeah, there was limitations with Abbey Road Studios. We all know that, but there was also the amazing studio with the real echo chambers, real, not digital delay. And it just kind of all comes together, if you’ll excuse the joke.

TMBP: They were also — and this includes George Martin — great editors, and they knew they knew what should stay and what should go. And whether during the songwriting process or whether in the actual recording of the song, knowing just what was too much, what they didn’t need. And it seems, again, in reading your book, that they were good at that with their films — whether it was in “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!” or “Magical Mystery Tour” — knowing what to cut, knowing what they need to rework, knowing what they need to shorten. And it wasn’t always just, “We’ll give you everything.”

SM: Right. I think that “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Help!”, that was a lot in terms of Richard Lester and whoever was editing which particular film. You know, “Magical Mystery Tour,” they had a lot of help with that too, in terms of editing it down and creating something that was close to being cohesive. “Let It Be” is this thing of just hours and hours and hours because of the nature of it, because it was a documentary.

I mean, keep in mind, they obviously have all of this control over their music as time went on. But with the films, it is very much collaborative and various decisions in the way things end up is very much the filmmakers’ and not the Beatles. “Magical Mystery Tour,” they had almost total control over.

TMBP: So I was saying, I have your 33 1/3 on “Let It Be” in my hand. On the last page (this is a spoiler alert for anyone who has not read it yet) you write — and this is right after they found the stolen tapes – “Whether the recovery of the stolen Nagra tapes will impact the fate of the new DVD remains to be seen.” When you wrote that 20 years ago, what did you expect would happen?

I meant it when I said I had Steve Matteo’s 33 1/3 on Let It Be in my hand. Please visit the Contact Me page if you’re looking for an inexperienced hand model.

SM: When I interviewed Michael Lindsay-Hogg, he told me that he was interviewed for extras for a DVD release. And there were other people that I talked to who said the same thing. Now, of course, it never came out. The whys, we don’t know. There’s always been this speculation that the Beatles didn’t like “Let It Be,” particularly George. And that was a lot of the reason why it kind of sat on the shelf.

This is after George passed away [in November 2001]. I’m working on the book mostly in 2003. So that must have been the impetus, in some ways, to say, “Now’s the time to get this thing off the ground. George was never really a fan.”

I don’t mean this in a negative way. They weren’t being like, “OK, George is gone. Let’s put this out.” I don’t mean that. That’s not where I’m going with this. I think that I think it’s just the opposite. I think they respected, they all had an equal share, and he really wasn’t a fan of putting it out.

So now that George had left us, I think that was one of the projects they felt like, “We don’t like it, [but] people want to see it. So let’s get it out there.” But it never happened. And whatever the reason, I don’t think anybody really knows that. If somebody knows it now, tell them to e-mail me and let me know. Was there something? Because they put all this work into it. And if you remember, also, when they announced “Get Back,” they announced “Let It Be” would be re-released.

TMBP: It was the last line in the press release announcing “Get Back.”

SM: Right. And so here we are, once again. It’s, as Yogi Berra said, déjà vu all over again. Every time they do this, people start calling me and they want to interview me. And I say this, the story of “Let It Be,” “Get Back” — whatever you want to call it — it is not over, it will not die, it will not go away.

And that was one of the reasons why I did the 33 1/3 book. Because I felt like of all their albums, that was the one that the life of it was not finished. It wasn’t something that was done. I mean, look at it. As much as they hated it, we’ve had Let It Be … Naked, we’ve had “Get Back,” and we’ve had the Let It Be box. And whatever’s on the Anthology albums, the CDs, and it’s still not over.

You have to remember, too, that Peter Jackson said that he’s going to work on another project with Paul and Ringo. And whether that is the “Now and Then” thing or whether it’s hopefully more like the Star Club-type stuff. I think it’s more than just using that technology to get better recordings out of some of this to put out. But I don’t know, I have no inside information.

TMBP: What were your experiences listening to the Nagra tapes? Because there aren’t that many of us who have put in the effort to hear it all. For me was very eye-opening to get this full breadth of who they were. You got little bits of it in all the bootlegs that came out from 1969 on, but then to finally get the full extent of it — what was that like for you?

SM: I was never a big bootleg guy. I know there was almost an industry of Let It Be/Get Back bootlegs, but it always intrigued me and it was interesting. And then when I started working on the 33 1/3 book, obviously I started really digging deep into this stuff, and it is fascinating. You do kind of get into it and the history of it, the photography, the pictures. I love the way that — and I talk about this in the new book — these bootleggers would come up with these crazy names for these things, like “Jamming with Heather.” I named the last section of the book after “Posters, Incense and Strobe Candles,” the BCN bootleg. I love that stuff.

I mean, I know some people think this stuff should all remain dead and buried. Some people want to hear every note. Steely Dan, they’ve never wanted to release all of the outtakes and all of that stuff. They have this aversion to it. I think they’ve released one unreleased song in their entire history. They just don’t want this, they are such perfectionists. They don’t want people to see Picasso’s sketches.

TMBP: At some point in the 1970s or early ‘80s, didn’t George Martin say there’s nothing in the vaults anyone would want to hear? But that wasn’t true. And then you have someone like Bob Dylan, who in his lifetime makes the decision to put everything out there. And I think that’s what the fan wants to hear.

SM: Neil Young is doing that too.

TMBP: And I want to hear everything. But I guess that’s me. And again, I don’t know how many people would sit through 80 or 85 hours of Nagra tapes or whatever the band’s leftovers are.

SM: They could make it available digitally or something. I think that Capitol, Universal, Apple — I think they’ve gotten better at it. I think that the Anthologies were the kind of first step towards doing this stuff right. Whatever problems they’re all with it, and everybody’s got their opinion. And then I think the next kind of leap was once they started with the Sgt. Pepper 50th anniversary, I think they’re getting this stuff right. And I think the reason why is because I think they’re trying to be more open to listen to what the people who really know have to say, not just relying on whoever the person is at the particular label at the particular time who’s in charge of catalog development.

“It all ended in 1970. I think they’re going to reach a point where they’re going to run out of stuff. But I think there’s still stuff left to be put out.”

TMBP: What was your reaction to the “Get Back” series, to hear the tapes cleaned up and see those visuals? There are moments in “Get Back” not quite portrayed the way it really happened, some scenes not edited sincerely – there are some gray areas. How did you view how “Get Back” was presented overall?

SM: What you’re saying in terms of your knowledge of it, where you know, they played with that, they enhanced it, or it’s a little out of sequence, which is troubling. But I think that’s just what filmmakers do.

TMBP: It’s a good story. Peter Jackson made a great story.

SM: Right. And I don’t think they’re necessarily trying to mislead anybody. I just think there’s a sense of it doesn’t make sense, even though it’s correct.

Because you know, “No, that’s wrong. That’s enhanced. They overdubbed something there.” But maybe they didn’t, maybe it’s just this new technology. They were able to fix it. Maybe it wasn’t right before because you couldn’t hear it right. And now it is right because you can hear it now because of the new technology. I mean, that’s a discussion to have.

TMBP: For sure. I’ve thought everything that Peter Jackson did was certainly from a good place. Maybe I’m speaking like this is the world of sports, but “Get Back” invigorated the fan base, so to speak, and then brought in so many new, younger fans. I’m on social media and shocked in the best way at how many teenagers, 20-somethings are knowledgeable and fully invested in the Beatles. I think these were the right choices at the right time, the right phase of the Beatles to blow this out.

SM: Yeah. I think that it was — these guys are so cool and not just the four of them, but all the people that surround them. Glyn Johns wins the “Get Back” Fashion Award. I don’t think there’s any question about it. I think that they, the world, the media world is so used to these long-form streaming shows, these bingeable kind of things. Rather than just watch some dopey show on network television or go to a movie, this is almost like a new format, for lack of a better word. And it was so smart to put it on the first time over Thanksgiving weekend, when everybody’s home for this long weekend, and everybody’s exhausted from eating too much turkey and drinking too much wine. We’re kind of in the middle of COVID. So it’s sort of like, “Well, what do you want to do tonight? Yeah, let’s watch ‘Get Back.’”

And the critics seem to really love it. It’s Peter Jackson, too. He’s like the biggest at that time. No one could touch him as a filmmaker. He’s like this old hippie, too. So I think he comes from, like you said, the right place. It wasn’t just, “This brilliant director guy, we’ll just have him do it.” Don’t forget the Beatles wanted to do Lord of the Rings. Well, here’s the guy that did Lord of the Rings. So how perfect is this? I mean, it really, once you heard that this was going to happen, it was like, ah, perfect.

Peter Jackson and Co. cross the Road during the mixing of the Lord of the Rings soundtrack in the early 2000s.

TMBP: Exactly. There was, there were a lot of ways they could have gone. And it couldn’t have gone better.

SM: I could have written a book just on that. I’m in the 11th hour on my [new] book, and at that point that I was able to say — and we were cutting a bit from that section — I could have went on and on and on. I could go back and really do the “Let It Be” book again as “Let It Be/Get Back.” That would make a great book. Someone’s going to do that. I know it. I wish it would be me, but I’m not going to go retread that area again. It doesn’t make any sense. It will not go away.

I think part of it is it’s the end of the Beatles. So no one wants it to end. It’s the one part of their period that no one wants to see. It’s metaphorically, on so many levels, you know what I mean? Culturally, musically, generationally. It’s just like, “Oh no, wait, the Beatles broke up. What do you mean?”

TMBP: “Get Back” came at a time with so many generations of people watching, so many more than had seen “Let It Be” first-hand. So you have people who experienced the breakup in real time and read Lennon Remembers when it came out. And it’s like, you know what? Maybe John didn’t really mean all those things. Look how happy he was in the moment. And then you have people who never dwelled on the breakup, didn’t live through it, watching these guys creating songs out of nothing. It kind of hit something for every kind of fan.

SM: It’s like a soap opera, too. It’s like “Downton Abbey” or something. It’s “Downton Abbey Road.” It’s like “Bridgerton.” I’m stretching here, obviously, but it’s all those hours. There was a time where people would be like, “What, how many hours is it? Forget it. It’s more than a half an hour. I’m not watching it.”

But we’re all so used to this now, with Netflix and Apple TV+ and Hulu. People don’t read anymore. They don’t read long novels, but they’ll watch the eight-hour limited series on Netflix. They’re hungry for that. They want to be told an enveloping story, but they don’t want to sit down and read Thomas Wolfe.

“You get to watch them, and they’re silly, and they’re hysterical, and they have no computers, and they have no cell phones.”

TMBP: They had no cell phones and they were busy reading newspapers. “Get Back” is a beautiful time capsule, and while in that sense it’s dated, watching the footage, it seems timeless.

SM: Right, exactly. That’s what it is. You get to people. So there’s no time machine. Well, yeah, there is, and it’s called records and books and movies. And either it means you go back in time or you read something that somebody wrote yesterday about something that either happened in 1965, or they made it up about 1965. So that’s the time machine. People are stressed. I mean, between COVID and Trump and climate change, and I could go on and on, people are kind of fed up. So you go back to the ’60s and everybody’s groovy and having a good time.

Yeah, there were other things going on like the Vietnam War, and the world wasn’t perfect, let’s face it. But if you look at it through rose-colored glasses or kaleidoscope eyes, there’s this phrase for golden-age thinking — everybody thinks because something happened in the past, it’s better because you see it differently. It seems simpler, but it really was better. I’m sorry.

TMBP: In watching “Get Back,” I was struck by Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s work. I guess we know why he edited “Let It Be” as he did — he had four Beatles to please in real time — but he edited his own film in such a different way than Peter Jackson did with “Get Back.” Michael took such spectacular shots and we had to wait 50 years to see them.

SM: He is a great filmmaker. And one of the other things that I liked about “Get Back” is, Michael and Peter — it’s a mutual admiration society. They both really, truly like each other and respect each other. Michael went on, as you know, to have a great career. Before the Beatles, he was one of the main people in the evolution of Ready, Steady, Go!, probably the greatest music television show ever. And then after the Beatles he did “Brideshead Revisited.” That was huge. That was a phenomenon when it came out. In terms of critical acclaim and in terms of the amount of people that watched it, that was the “Downton Abbey” of its day. And of course he did other things, and he’s a painter. And I tell you what, he’s the nicest guy in the world. I’d like to hang out with him. He’s so talented. He’s a renaissance man. He’s a throwback. He really is, truly. And he’s royalty, too — he’s a baronet.

I’m glad that he is getting his just desserts, in a good way. That’s another reason why I would like to see “Let It Be” come out. Because I think that it will be reevaluated. And I think that Michael deserves his moment in the sun.

“Whether they’re collectively or as solo artists or the various labels, there’s so much material to re-put out again.”

TMBP: Twickenham Film Studios is part of their entire career. They’re going in and out of Twickenham, whether it’s for movies or promotional films, all these different things. Was that the only real feasible location in the UK or in London for such a large-scale operation?

SM: No, there are other places to make movies. I just think Twickenham just happened to be the place. I think it was just kind of happening at the time. I think maybe United Artists also had some sort of connection with them. It was probably the most fulsome setup. It was maybe a little bit more centrally located than some of these other studios that were a little farther outside of London than Twickenham was. They could just become like, ‘Oh, we just happen to work here first.’ And then they’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, that worked out fine.’ So we’ll just go back there again. There’s not a lot of thought put into it.

TMBP: It’s like always going to EMI when you could go anywhere. I’ve always wondered if there ever any suggestion — and presumably wouldn’t be from them, but who knows – of shooting something in Hollywood. You would think that would be fun, at least for them.

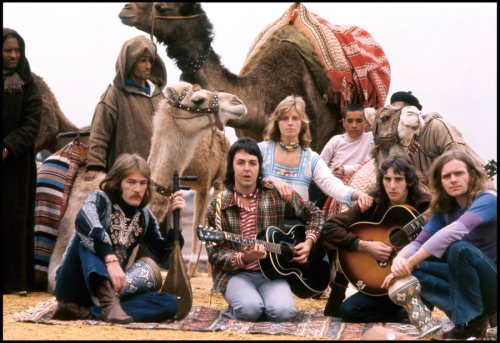

SM: “Magical Mystery Tour” is mostly shot on location. And I think they even tried to film some scenes at Twickenham, but it was all booked up. And that’s why they used that big Air Force hangar, because they couldn’t get into one of the film studios at the last minute.

TMBP: And thank God they did that, because the “I Am The Walrus” sequence one of the great scenes in their history.

SM: And then “Help!,” obviously, is shot on location in the Bahamas and Austria. And “A Hard Day’s Night” is mostly shot on location. So yeah, they did a lot of promos at Twickenham. They shot almost half of “Let It Be” there. So I don’t think there was necessarily that much thought that went into these things. I think maybe it was just a question of a certain comfort level, you know?

TMBP: Sticking with “Magical Mystery Tour,” should that have been a cinematically released film instead of a TV show? We see how influential “Yellow Submarine” became, acknowledging how they weren’t involved with it. But would “Magical Mystery Tour” have had that same sort of acclaim had it been in theaters instead of on TV in 1967, and changed its historic trajectory?

SM: I think it was a film, but I think it was a short film. Let me just qualify that. And then, why it was shown on television? I think it was because they really couldn’t get film distribution because it was so freaking weird. And also it wasn’t the length of a feature film. So again, they’re in this weird place. I think they wanted to show it on television because I think they wanted to get it out quicker. And I think they perceived it as almost like partially, believe it or not, as a promotional tool. So if they released it as a film in the shape that it was in, and what I mean is by length.

And it was just shown at universities and at the UFO Club or Middle Earth or whatever, I think that it would have gotten the avant-garde media, underground media, which was ‘67 is just really coming into place. Rolling Stone magazine launches in October. I believe FM radio was actually around in ‘66 in New York with WOR. So you’re just getting the beginning of sort of the underground. I guess you have Oz magazine … and it’s very underground. So if it’s shown as a film in the kind of places where those kinds of people go, and it’s only covered by that media, then maybe it starts out in a different sort of spot. It was wrong for it to be shown the way it was shown, particularly on the date, but we all know that.

TMBP: Why was it kept off American TV for so long?

SM: NBC turned it down. They just thought, “This is just too weird. We’re not going to show this stuff.” You have to remember this is 1967. If you’re in New York or San Francisco or London or maybe some places in Colorado or Boston, yeah, you’re plugged into this counterculture underground, this thing is happening. This is the next phase.

It comes out after the Summer of Love. So we’ve been through all of that. It’s not quite the tail end of psychedelia, because psychedelia starts and ends. It’s a wide period of time, but the peak is a short period of time where it sort of peaks.

TMBP: What’s your favorite Beatles film?

SM: I think “A Hard Day’s Night.” Without getting into a long-winded explanation, I think “A Hard Day’s Night” still the best, it is still such a great movie. It stands on its own as a film. You can watch it and kind of separate the Beatles from it, but you can view it just a film. And it’s just great, it’s an important film. It’s part of this evolution of ’60s cinema, where you can’t really say that about the other films. Maybe “Yellow Submarine” in terms of it being the first sort of major important animated feature-length animated film for adults. But I think it’s “A Hard Day’s Night.” Give a lot of credit to Richard Lester.

Is that your favorite? Or is it “Let It Be?”

TMBP: It’s “Let It Be” and it’s sort of in a sick way, but I recognize “A Hard Day’s Night” as their greatest film –- I acknowledge the separation between favorite and best. What about something that someone else has done about The Beatles? Is there something that stands out?

SM: “Anthology,” I really would like to see it again. And I would like to see them fix it. I don’t know if you’re into Pink Floyd, but they took one of these films, it was from the ’80s. And what they did is they went back and they completely redid it — they made it in widescreen, they took away some of the clunky sound of it. They did a restoration to it. I would really like to see that done with “Anthology.” And then I think I would have a certain feeling about it.

I really loved “Across the Universe.” I thought that was really beautifully done. You know, it’s hard to kind of make a movie like that. I really like “The Beatles and India” film a lot. I thought that was really, really wonderfully done. I remember seeing “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” when it came out in the movies. It was kind of cute, the idea of it. I think it was done with a lot of heart.

“Backbeat,” that’s probably my favorite, I love that movie. Everything about that movie just works. “The Concert for Bangladesh” is a great show. It’s a time capsule. I can remember, I had just gotten an FM radio of my own, a whole stereo setup. And I remember them playing that on the radio, premiering it and playing chunks of it in a row on the radio and just being blown away by it.

TMBP: “The Compleat Beatles” was really formative for me.

SM: Yes, me too. I have that on VHS. That’s never come out on DVD or Blu-ray. I think they’ve lost all the rights on that.

TMBP: The Beatles have all these little pockets of things that we’ll never see ever again. Or, who knows when we’ll see it, whether it’s “Let it Be,” or “Anthology.” I mean, unless you own the physical media.

SM: I think they will put those out. I think you’ll see these things — when, I don’t know. I hope they don’t just do like what they did with the rooftop concert audio, where they just put it out on streaming only. To me, I don’t think they know who their audience is when they’re doing that. You know, their core audience is still is physical media people. Especially vinyl. Now maybe their plan is at some point to do that, but I thought that was awful that they did that.

TMBP: Paul did something similar with the Flowers in the Dirt box set, where more than a dozen songs -– demos, B-sides, remixes – were bundled for purchase and download-only.

SM: If you see the way that they’re discounting some of this stuff, I think that from their point of view, whatever numbers they had in mind, I think there’s a certain degree of disappointment. I think it’s selling a lot, but I think that sometimes I think they have an overinflated sense. I also think that they, what they want to do is if they print a 100,000 copies, they’ve got to sell every last one. Like they want to wring out every last penny from it.

And I know that Disney did not handle the “Get Back” reissues on Blu-ray. That was not handled right. They did a terrible job on that. It was almost like they didn’t even want to do it. I have this conversation with my wife all the time — there was a time that a record, an album, a CD, a DVD, a Blu-ray, people love this stuff as a gift, because there’s a certain personal connection there. And it’s an inexpensive gift. Twelve-inch albums aren’t small, but it’s relatively small. It’s value for money too. Some of these are things people don’t want to spend the money themselves. They think it’s extravagant, but if you give somebody a $25 Blu-ray or if you give them a nice double vinyl album, they’re like, “Whoa, thank you.” And these record companies and film companies that want to phase this stuff out.

“Once you buy a record or a CD or, or an album or a book, you own it. It’s yours. You can do whatever you want with it. You can have it forever. They don’t like that.”

TMBP: : Your book stuck to the core films. Did you consider writing about “Anthology” or “Eight Days a Week” or anything like that?

SM: The only one that I thought possibly could have been included was the Shea Stadium concert. But again, I felt like it really was just a television show and it just would have made things so much more complicated. I think that those five films is the way that it is. That’s the canon, so to speak. I don’t think Shea Stadium is really part of it. I touch on Shea Stadium, but again, then the book becomes, it becomes unwieldy. It really ended, I have to let it be. That’s it. It’s over, you know? I mean, I give you a little sense of how these ’60s films would go on to influence. And then I give you a laundry list of film directors — Marty Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola and Robert Altman and the usual suspects, how important ’70s American film is, how that kind of takes over. That’s like the golden age. Again, there’s that phrase, you know?

I thought about maybe at the end, I could put a couple of pages of a capsule review of some of the films that came after, but then where does it end? I’m having trouble with the length of my manuscript to begin with. So to even think about that, maybe that’s a Part Two, but I don’t know if I would ever actually do it.

I should probably have one of these disclaimers: Steve sent me a review copy of the book. But in all honesty, I would have bought it anyway.