“I canceled the papers last week,” George Harrison told the rest of the Beatles early on January 9, 1969. “And they won’t stop them coming.”

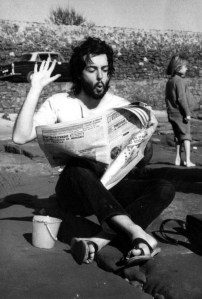

Whether George reluctantly toted the Daily Express and Daily Mirror from his Kinfauns home or if they were delivered otherwise to Twickenham Film Studio, the newspapers were put to good use by the Beatles that Thursday.

“It’s about going away, and then the chorus is ‘Get Back.’ Actually, it’s not about anything.” – Paul McCartney

When looking for inspiration, we all know of John Lennon’s willingness to read the news (oh, boy), but it was Paul who ripped from the headlines to fill out some lyrics in his signature song on the sixth day of the Get Back sessions.

“Get Back” emerged from a jam two days earlier with a small set of lyrics — most of which would ultimately survive — including “she thought she was a woman, but she was another man,” “say she got it coming, but she gets it while she can” and “knew it couldn’t last.” The chorus would never change: “Get back to where you once belonged.”

The newspapers informed additional verses to give meaning to the chorus.

But first, let’s get back to George’s opening quote. After complaining about the papers’ non-cancellation, he continued: “George Gale is such an ignorant bastard.”

Gale, who at the time wrote for the Mirror, probably caught George’s venom because of that day’s column ridiculing marijuana users in the context of the release of the Wootton Report on the potential decriminalization of the drug.

But pot, for people in this country, is a new way of fooling themselves. A man is not made more free by taking pot. Quite the reverse. He is simply made more stupid.

The whole column is the opposite of “Got To Get You Into My Life,” so the reason for disdain is obvious.

But Gale’s politics would have been antithetical to George and the rest of the band since their teenage years. It was in 1956 — the year the Quarrymen were formed — that Gale famously wrote under the headline: “Would YOU let your daughter marry a black man?”

Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech was given in April 1968, less than year earlier, and its impact continued to resonate (Powell will soon enter this day’s story, too). Race issues remained a terrible plight and severely divisive issue across Britain into 1969 — and, obviously, before, beyond and basically everywhere throughout human history. In the specific context of immigration to Britain, it was in front-page news on January 9 as the Daily Mirror shouted on Page 1: “WARNING TO THE PREMIERS: NO EXTRA IMMIGRANTS”

Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech was given in April 1968, less than year earlier, and its impact continued to resonate (Powell will soon enter this day’s story, too). Race issues remained a terrible plight and severely divisive issue across Britain into 1969 — and, obviously, before, beyond and basically everywhere throughout human history. In the specific context of immigration to Britain, it was in front-page news on January 9 as the Daily Mirror shouted on Page 1: “WARNING TO THE PREMIERS: NO EXTRA IMMIGRANTS”

BRITAIN has no intention of easing her immigration restrictions to take in extra Asians forced out of East Africa. … Mr. Callaghan insists that if Britain is forced to take more Asians from Kenya and Uganda, there will be a cutdown on other Commonwealth immigrants. The Home Secretary is giving the Premiers the strongest warning yet of serious trouble in Britain if extra migrants have to be accepted.

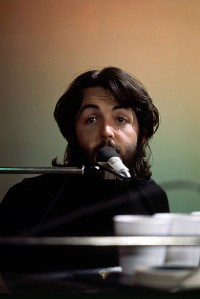

And that takes us back to “Get Back,” the first song the Beatles worked on after lunch. Musically it surges, spunky and alive with the four Beatles perhaps recognizing this is the upbeat rock song they were searching for a week into the sessions. It was likely the first time John played on the song, having arrived after the others when it was first played two days earlier.

From a purely musical standpoint, the song was hot and was rivaled by “One After 909” at this point in pure energy — as far as their originals were concerned. By this early moment in the song’s life, it already had the guitar riff and Ringo’s identifiable cymbal crash during the chorus.

“Think of some words, if we can. I don’t know what it’s about,” Paul admitted. “It’s about going away, and then the chorus is ‘Get Back.’ Actually, it’s not about anything” (said to laughter).

That was fine with George. “We’ll just have those words, just words like [the Band’s] ‘Caledonia Mission.’ They’re just nothing about anything, it’s just rubbish.”

So don’t count George as finding any deeper meaning into that Big Pink cut, in its hexagrams or Arkansas towns. The movement Paul needed was on his shoulder: Just write words that track to the tune, regardless of any actual meaning, and it’ll all eventually shake out.

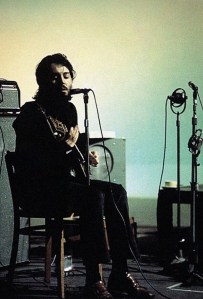

Despite Paul’s admission to the contrary, to this point, the song did start to find a vague lyrical angle. Joe and Theresa entered the picture this afternoon — JoJo and Loretta would join eventually in their place. There remained the pursuit of California grass. Tucson — the Arizona city in which Linda Eastman went to college and close to where the McCartneys would later own a ranch (and Linda would pass away) — was specifically named for the first time.

Additional lyrics — often turns of phrases rather than coherent statements — emerged during the more than 20 minutes of high quality and high energy vamping and jamming. One pass through the verse is in the first-person, with the singer the protagonist who was a loner leaving his home for California and who was getting back to where he once belonged.

But for the majority of the rest of the time, Paul draws from the immigration news in his search for a relevant lyric, alternating verses about a Puerto Rican and a Pakistani, with the East Asian community’s flight from Kenya still such a big part of the news in Britain. (As a footnote, Paul visited Kenya in 1966, going on a safari with Mal Evans)

There were several points where Paul simply garbled over a name, phrase or section of lyric just for filler. Elsewhere, we get the beginning of a narrative, with an intolerant public imploring the different nationalities “get back to where they once belonged.”

A sampling of lyrics:

- A man came from Puerto Rico, oh, he joined the middle class/Where I came from, I don’t need no Puerto Ricans

- Take the English job, only Pakistanis riding on the buses, man

- All the people said we don’t need Pakistanis, so you better travel home

- Don’t dig no Pakistanis taking all the people’s jobs

- Don’t need no Puerto Ricans living in the U.S.A.

- Don’t want no black man

When tapes from these sessions first leaked into the bootleg market in the mid-1970s, we would simply get single songs stitched together with no context, little dialogue and guessed song titles — like ones called “No Pakistanis.” It’s obvious the Beatles were simply making a social commentary, satirizing the segment of the public who harbored the feelings they were singing. But by the mid-80s, a wide exposure of these takes by The Sun — lacking the needed conversational context or tracing of the evolution of the song — posited the Beatles must have been xenophobes themselves. Gotta sell papers, after all. There probably aren’t too many times Paul ever commented on bootlegged tapes, but Rolling Stone got him on record in 1986, responding to the racism claims:

Sensational journalism – The Sun is not a highly reputable newspaper. What this thing is, I think, is that when we were doing Let It Be, there were a couple of verses to “Get Back” which were actually not racist at all – they were antiracist. There were a lot of stories in the newspapers then about Pakistanis crowding out flats – you know, living sixteen to a room or whatever. So in one of the verses of “Get Back,” which we were making up on the set of Let It Be, one of the outtakes has something about “too many Pakistanis living in a council flat” – that’s the line. Which to me was actually talking out against overcrowding for Pakistanis. The Sun wishes to see it as a racist remark. But I’ll tell you, if there was any group that was not racist, it was the Beatles. I mean, all our favorite people were always black. We were kind of the first people to open international eyes, in a way, to Motown. Whenever we came to the States they’d say, “Who’s your favorite artists?” And we’d say, “Well, they’re mainly black, and American – Motown, man. It’s all there, you’ve got it all.” I don’t think the Beatles ever had much of a hang-up with that.

The reference he makes to the line about “too many Pakistanis living in a council flat” actually came on January 10, when the Beatles continued to work on the song. But the point remains. The song has been misunderstood by some unwilling or unable to see the nuance (search around the Internet for “Beatles” and “racist” at your own risk, even moreso if you read any comments).

We have on tape evidence the “get back” element of the chorus came before anything else on January 7, and was likely a riff on Jackie Lomax’s “Sour Milk Sea,” and we can reasonably dispense of the myth the song’s true origin was political. It’s also pretty clear Paul simply liked the flow of “Pakistani” and “Puerto Rican” — words with four syllables that were easy to rhyme — and was searching for something that sounded appealing, while not shying away from something political. At one point he clumsily rhymes “Puerto Rican” and “Mohican” (a Native American tribe), a perfect example of how little thought out the lyrics were at this point. He was just searching.

John Lennon later said “Get Back” was directed at Yoko Ono, anyhow. But more on that another post.

The 20-plus-minute post-lunch writing and rehearsal session marked the end of the group’s work on “Get Back” for January 9, although they’d return to it nearly every day they were in the studio until the end of the month. It wasn’t the last time the group included the racial element in the song, and it wasn’t the last time they’d address the issue in song on January 9, either.