OK, stick with me here.

Nearly 46 years ago, somewhere between lunch and the resumption of the day’s writing session-cum-rehearsals for “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” it sure sounds like Paul McCartney may just have invented the mashup, or at least a rough approximation.

Really!

This is not a medley, sampling, sound collage or musique concrete a la “Revolution No. 9” and others before it. This is turn-of-the-21st century-style mashup: Think The Grey Album, Girl Talk or the Beatles’ own Love with elements of two or more songs layered on top of each other. The kind of stuff Paul got roped into a few years back before an audience, he and George performed live to tape decades earlier in a little bit of completely obscure history.

That would be 1967’s “When I’m 64” (written a decade earlier as one of Paul’s first songs and described here by Paul as the “beautiful geriatric Beatles song”) sung atop “Speak to Me,” which would ultimately lead off Jackie Lomax’s debut album, as produced by George and released two months later. We already heard George briefly play a more proper version of “Speak to Me” to John a few days earlier.

As Paul’s “When I’m 64” vocals eventually drop out – and his mouth clicks chime in – we go from a forgotten moment of debatable history to one that would have a lasting impact on wax: the debut of Maxwell’s actual Silver Hammer, the anvil, as ordered before lunch.

The band comfortably eases out of “Speak to Me” with a fun and increasingly polished run through of “Oh! Darling” – polished for this point in the sessions, for sure – the second time they played the song in a few hours, and with John having rejoined the group back on guitar. The song is essentially complete and by all accounts should have been by now part of the core considered for the live show at this early stage. It doesn’t get any further attention this afternoon as Paul immediately returns to “Maxwell’s” for the better part of another hour. This initial launch into the song is captured in the Let it Be film, spliced in from the point where Mal strikes the anvil. It’s a truncated slice of the song, and in the film we end up getting thrust into the Shoctric Shocks incident, which actually occurred four days earlier.

Paul doesn’t introduce any new wrinkles yet in this first go-round after lunch. He’s pleased, though. “It’s catchy enough, then,” he says after the first full take. He soon boasts of the dramatis personæ and vibe of the song, “It’s so cartoon … such caricatures.”

Paul remains a delightful caricature of himself, remaining fixated on the whistles that color the song throughout. “We want a mic for John and George on this ’cause the whistle on this,” is Paul’s first and primary direction to the crew. George’s initial concern in the early going of the post-lunch session is getting the song’s timing and cues down, especially for the sake of Mal, who wielded the hammer. Not that George didn’t try to give his drummer an additional bit of work.

“I’m sorry, George, the hammer’s too heavy for me,” Ringo says to laughter. As it turned out, Ringo would end up carrying that weight after all, striking the anvil in July, when the group properly recorded “Maxwell’s” for Abbey Road.

By Paul’s thinking, the roadie was the man for the job.

Mal’s more like Maxwell, anyway. … He should be very scholarly. Very straight, in a striped tie and a blazer, sort of. Big chrome hammer. That’s how I see him anyway. [He’s] Maxwell Edison, majoring in medicine, in fact.

Resplendent in a smart gray blazer and striped tie, Mal Evans is already dressed for the role of Maxwell Edison, medical student, as he rides the Magical Mystery Tour bus.

Sparked by a question from George about the repeated of “bang, bang” in the chorus, Paul runs through the song structure again with the usual caveat: “I haven’t written the last bit.”

That’s fine with George, who thinks he knows how the song goes. “I just know it in my head, rather than the words, because the words are not in the right order anyway.”

Loose as he can be, Paul repeats the song structure: “It’s like two verses (scatting and singing) Bang, bang. … Clang, clang. … Whistle. … That’s nice fellas.”

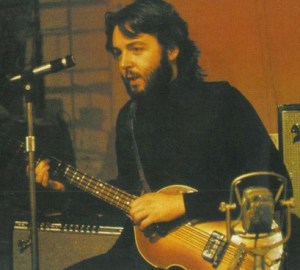

As work continues, George shows a bit of concern with his own instrumentation.

George: To the man that’s producing me, whenever I play bass, because I don’t know anything about it, I don’t know what the sound is. I just plug it in and play it. So if somebody knows how to get the sound or record it. I mean Glyn’ll have to do that if he’s around. So you can mention that to him.

That’s some pretty self-deprecating talk from George, but he really has few bass credits under his belt to this point.

Straight out of the Small Faces’ playbook, John ad libs a narrative introduction to the song, laying out Maxwell Edison’s origin story, with Paul picking up in the middle.

John: Let me tell you the story about Maxwell’s Silver Hammer. He got it from F.D. Cohen, the pawnbroker from Bayswater.

Paul: Maxwell was a young boy just like any other boy, and he might’ve lived a life like any other young boy’s life had it not been for some certain unforeseen circumstances.

And … whistle!

Given that the band spent more than an hour on the song of about five hours of recorded tapes this day, it’s no surprise it was a very early contender for the live act. So much so, George began offering up suggestions on how to stage it, beyond costuming for the band and Mal. There’s a practical side to his suggestions, too.

George: I think we can do it with lots of people singing the chorus, ‘Bang, bang, Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,’ but it’s very difficult for me to whistle and sing and keep in sync. … It should be like the end of [Hey] Jude.

John: ‘You all know it, join in, gang, because we don’t know it.’

George: We could just project it up, have the chorus projected up there.

We’re not sure what Paul thinks of that idea, since there’s whistling to be done, and no joke whistling, please. “Really, do it like it’s straight,” he says, telling George how the notes of the chorus solo goes. That’s a whistle solo, not a guitar solo, mind you. Paul does work on improving the song, spending a few minutes crafting a harmony based on a short, partial climb up a scale “with jumps on the hammer,” in his words. It’s pretty and adds to the carnival-like atmosphere the song has to this point.

For the final takes of the day of the song, the rest of the group still doesn’t have the song’s structure completely down, and Paul resorts to vocal cues to alert when the whistling solos come. John asks Paul to shout out “blow it, boys” at the appropriate time. Paul can’t help but repeat his helpful reminder: “It should be very straight, the whistling.” He really does keep saying this, to a near obsessive state, and at no point is he kidding about it.

The “Maxwell’s” rehearsals for the day end with a final, full run through. The song’s basic elements are there: new harmonies, whistle solos, the anvil and a full strong structure. What it lacks is a complete set of lyrics, but Paul isn’t sweating it, concluding with a simple, “OK, that’s Maxwell’s.”

While the song did progress with the work on Jan. 7, there was a noticeable missed opportunity shortly after lunch as a lead-in to the mashup sequence. For a few brief moments as the group warms up, a sloppy yet sincere take of “Maxwell’s” features Ringo on vocals, and it sounded like the perfect fit. Paul’s song eventually drove the other three Beatles to fury; giving Ringo an extended vocal role could have changed a little corner of Beatles history.

As the sessions continue, John takes the reins for the next song, one that not only has its lyrics set, but the instrumentation as well.

“Should we do ‘Across the Universe?’ We almost know that, don’t we?”

Beautiful! The early timeline is clarified and confirmed: Five days from this is Jan. 12, a week before Jan. 19. Falling within the estimate drawn from their discussion the prior day —

Beautiful! The early timeline is clarified and confirmed: Five days from this is Jan. 12, a week before Jan. 19. Falling within the estimate drawn from their discussion the prior day —