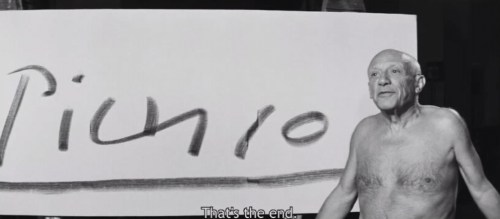

At the conclusion of the 1956 French documentary “Le Mystère Picasso,” the grand old painter splashed his iconic signature on a print and announced (translated to English), “That’s the end.” He wasn’t bargaining with director Henri-Georges Clouzot, himself considered a master in his field. It was a declaration: This film was over.

Pablo Picasso’s paintings and his exhaustive creative process were the focus of the film, his hand usually invisible as it brushed across a transparent screen, at times in black and white, and at others in vibrant color. In the film, Picasso produced several completed paintings, and we catch occasional glimpses of him at work, creating art out of nothing in an spartan studio while holding an occasional dialogue with the film’s director. This should sound familiar.

Paul McCartney had a few occasions to come across the film. It was screened in Liverpool in June 1958, when Paul turned 16 and was nearly a year into his creative partnership with John Lennon. But odds are Paul saw it sometime between late January and March 1967, when the film was shown at the Academy Two in the West End, about 2 1/2 miles from where the Beatles were recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and a very short walk from other frequent haunts like the Saville Theater and the Bag O’Nails. (The documentary was broadcast on BBC-2 in May 1968, as well, but Paul was in New York at the time).

One of several films considered a reference point in the early afternoon of January 13, 1969, “Le Mystère Picasso” was mentioned by Paul as an inspiration to Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who was in the midst of directing what became known as the Beatles’ Get Back project.

“They don’t sort of fast-cut the paintings,” Paul said to Michael. “And these songs are going to be our paintings at the end of it.”

The endgame for the Beatles’ documentary of the creative process was unclear even as the documentary was underway. And unlike Picasso, here the creative powers continuously bargained with the director.

That Paul, with a comparatively quiet Ringo Starr, would even waste time debating with Michael speaks to the confidence the band had to to see out this project.

Yes, yes, and then there were two. So what, the show must go on. And that’s why the Beatles were at Twickenham Film Studios to start 1969, after all: to stage a show. The rhythm section was in tow relatively early that Monday. Of the missing half, one member had already decisively quit while another was frustratingly unreachable.

Having recapped the previous day’s difficult meeting that saw George Harrison ultimately walk out in large part due to the disruptive dynamic between John and girlfriend Yoko Ono, the present conversation only looked ahead.

This initial sequence first appeared on film in the 2021 Get Back docuseries.

“If we were going to take a ship’s pool on what our communal life is going to be in the next two weeks, what are we all betting?” Michael, in his imitable way, asked Paul and Ringo.

Paul shared his hopes the current state of limbo would only be temporary. “I think we see the end of this week out,” he said. “And something will have happened, definitely. … Then we’ll say that we don’t come in next week and we sort of chuck it. Or, we come in next week, and .. make it next week.”

“Then we send the guys off to Africa,” Michael chimed in, to laugher.

Paul continued, laying out the actual logistics.

“We’ve got to stop the clock while this is all going on. Like, this isn’t counted. We should cancel that [January] 18th date, ‘cause it should definitely be the 19th already, ‘cause we’re going to lose today.”

Timing mattered, and so did location.

“We should do it here,” said Ringo, again. His desire to stay in England was a true constant in January 1969, and he only briefly toyed with the idea of traveling a few days earlier. But that was then, and now, there seemed to be true consensus on staying put at Twickenham or nearby — and that included the better halves.

Paul: I don’t really see any point anymore [in going overseas].

Ringo: There were eight of us who didn’t see any point.

Paul: And luckily we’re the Beatles, who don’t see any point.

As had been the case for nearly two weeks, while they may not have known what they wanted out of the show, they knew what they didn’t want. At least Paul knew, speaking on behalf of Beatles present and otherwise unavailable.

At once a touchstone and a millstone, the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus was filmed a month earlier in London under Michael’s direction and with John as one of the performers. Paul, who had seen an early cut of the film — it wasn’t released commercially until 1996 — made clear the fast-moving Circus wasn’t a format he wanted to follow, continuing to deflate Michael.

“It didn’t look right,” Paul said. “I know it was a bad print. But like, I didn’t ever get into any one of the Who. Ever. It was the event all the time. And no one digs that. That’s over, that sort of event, I think. It really is now, if you’re trying to show him, I just really say just stick [the camera] on him.”

A “study.”

That’s what Linda Eastman suggested, and Paul repeated.

Here’s where the conversation turned to “Le Mystère Picasso” — it showed up as “The Picasso Mystery” in British movie listings. Anecdotally, Paul called it “Picasso Paints.”

Michael contended the documentary the Beatles were filming — not the grand finale concert, wherever it may be, but this ongoing build-up — was the study, but Paul suggested the examination should extend into that live performance. He saw “Le Mystère Picasso” as analogous to this Beatles concert.

“They didn’t sort of fast-cut the paintings or anything,” Paul said to Michael, who was also familiar with the film. “He just sort of painted them. They showed how he built up, and they stayed on it.”

There’s a bit of a straw-man argument going on, since Michael never contended he should litter the film with quick cuts. To the contrary, he complained about that very technique in the recently broadcast Cream Farewell Concert.

Paul brought it back to the Circus, and justifiably, as it was Michael’s most recent production and featured fellow A-listers. It wasn’t just contemporary, but it was competition. (And perhaps moreso personally so for Paul, with John having been a Circus performer). January 1969 had seen a lot of wandering discussions on where a Beatles concert should be. Here Paul — speaking over Michael — explained how he thought it should look, regardless of location.

“Very, very bright lights, so you see every detail about [Ringo], instead of moody things. Really totally bright-lit, it hardly needs scenery or anything. Really should be about him and his drum kit. … Says it all.

“And then John: his amp, his guitar. Actually sitting there, doing it at that minute. I think if you start going in that direction, then, I think you might think of a great idea. ‘Oh, incidentally, we think it all should be done in a black bag or something.’”

Michael pushed back, saying the Circus had a very deliberate design.

“You can’t compare the two,” Michael said. “The Circus was designed as an event. It was a different concept. The Rolling Stones needed a family show, and Mick [Jagger] wanted a family show. Mick said he wanted Ed Sullivan without Ed Sullivan.”

I’ll leave the analysis of Mick’s motivation to the Rolling Stones writers and researchers (free blog name suggestion: “Traps for Troubadours”). Those intentions, though, eventually impacted the Beatles’ decision-makers.

“You don’t go off Ringo,” Paul clarified. “Don’t go off into the scenic backgrounds. Or the audience. Or the moon. It’s not necessary.”

Swept up in the vision, Linda said, “God, you have it. Ooh.” Overwhelmed by the very thought of the Beatles, she quickly giggled before regaining her composure. Linda wore her love of the Beatles on her sleeve. It went beyond her personal affection for Paul.

Paul’s right: Michael did cut away from Pete Townshend as soon as he finished the windmill. (From Rock and Roll Circus)

“I missed a lot of that Who thing the other day,” Paul continued, with Linda occasionally interjecting and overlapping her agreement. “Pete Townshend, I never saw him. I’d really like to look at him for a long time cause he fascinates me. … I’d like to really just see what he looks like after he’s done that thing (presumably his windmill guitar move). …

“You know, [I’d like to see] Keith Moon just sort of jabbering away on the drums, just for a whole number almost. OK, so you’re going to have to cut between the four of them. But it’s just that thing, really sticking with it. And I think that’s the point of this show, for us.”

Paul evoked the news again.

“The really good coverage is the shot of the fellow with the gun to a head, and the fellow who got that [camera] shot, that was the man who covered the event,” Paul said a few moments earlier. “The fellow who got the guy on the ground afterwards with the blood coming out of his head missed it. And with all that fast-cutting, [you missed it].”

Less gruesome comparisons continued. It emerged as the best way for the director and the talent to triangulate an acceptable idea for their own production:

Top of the Pops: Michael said “they never help the act. … If you just take a wide shot of [the Who] doing their act, with no particular response from the audience, they do look like they’re lunatics, but the wrong kind of lunatics.”

Ringo brought up a recent appearance from Crazy World of Arthur Brown, whose single “Fire” hit No. 1 in Summer 1968, to prove this point. “The camera needs to do something. And Arthur Brown, every time he came on … he’s so wild, and the camera’s going wild so you didn’t see anything.”

The “Hey Jude” promo film: “The comment about ‘Jude’ was that when I was doing those high bits, you didn’t see me doing them,” Paul complained to its director.

Michael, for his part, expressed regret at how the sequence turned out.

“I physically couldn’t get a camera onto you because they couldn’t hear the talk-back,” he said, referring to communication with his crew. “I should have been ready for that, but it was a mistake.”

An excerpt from “an old film” on TV the night before (probably something shown during Film Night on BBC-2): “They came down on the rooftops of Paris,” Paul said, with Glyn and Michael saying they saw the same sequence, too, at 11:15 p.m.

“And that’s really where this should all be at Twickenham. This should totally be built like those film sets. So that you can glide all over the place like on tracks and everything with your cameras, go to places that TV cameras don’t go. So you can come down out of that roof, on one long shot, right from the back there, and just come down on a thing. Slowly, like a chair lift, right down, right into Ringo’s face on the one shot, from right back from there. It’s like the old films, and have all sorts of cranes and lifts and stuff for your cameras to float around us. And just all that flowing movement. And then the songs, you know? And just really stay with us. And then that’ll create your sets then, you’ll have cameras hanging all over the place.

If that sequence sounds familiar, it should: It was included in the 1995 Beatles Anthology documentary. It was not included in Get Back more than a quarter-century later.

Linda continued to be unable to resist the Beatles on film, even as she sat with them in person. “Mmm, but just them,” she said.

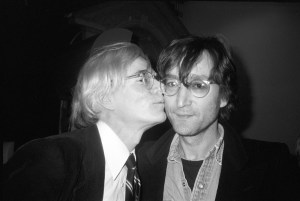

Andy Warhol’s Empire: This was a cautionary tale. It’s one thing to linger on Ringo’s drum kit for a three minutes. It’s another to have a single, black-and-white shot of the stationary Empire State Building for eight hours.

“That idea of slowly getting into the thing and being careful not to miss anything … I really do think you’ll find the pace is there without you having to put it there,” Paul tried to explain. “It’s like with Warhol’s things is that he does go right in to the other extreme. He reckons his pace in that Empire State [sic]. But I wouldn’t agree with him, I’d think he’d be boring, but I see his point.”

Glyn does too, but he falls in with Michael, arguing that a slow study could work for a few songs, but not for a 52-minute show.

“If we’re doing that, then I really think we should do galloping horses and really go the whole hog and really have an epic,” Paul replied. “But if we are going a bit towards the Beatles, I really think get the close-up lenses and get right into one of John’s eyes. Can you do that? Look in that direction rather than trying to get a picture of John and the moon or a big amphitheater.”

It was at this moment — not Paul’s “and then there were two” line but around 15 minutes later — Paul exits the stage to speak to John on the phone.

Deep as the Nagra tapes go, and despite Michael’s prep to bug the phones, we don’t know what was said on the call. We do know the conversation continued without Paul. The top storyline coming out of the meeting at Ringo’s the day before was the frustration of Yoko speaking for John. Here, in Paul’s absence, Linda doesn’t just speak in line with Paul, but she advocates for herself, too. This sequence appears in part in Get Back.

“I have never seen a study of any musical event,” Linda said. “You want to be there, that’s the thing. (Speaking forcefully) And if I were there, I’d be staring at them. I’d never look around me once. I’d be staring at them if I were sitting in the audience. It’s like you see in the theater. Why can’t the camera be you sitting there?”

Linda’s tone is outspoken and sincere, and something that was needed to move the conversation forward, her viewpoint as an artist and a fan. It clearly put Michael at unease and somewhat on the defensive in what emerged as something of a tense, sarcastic exchange that didn’t go unnoticed 52 years later in Get Back.

MLH: I saw their last concert at Hammersmith … and I was totally aware of not only them, and they were 40 miles away [sic], but the audience, the screams, the lights.

Linda: We looked at Help! the other night again and Hard Day’s Night. And that was them playing.

MLH: Right, but it was them over an hour and a half and 30,000 [feet high]. If it is an Andy Warhol picture …

Linda (fed up and combative): Oh, don’t take the other extreme! Andy Warhol, that’s not you! .. I’m speaking like a fan! I really am.

MLH: I am too. I’m a bigger fan than you are (said laughing, and with complete sincerity)

Linda (gruffly): Oh, OK should we fight about it?

MLH: I can do it any way. But being the fan I am, I gotta keep saying I think you’re all wrong.

Linda: You want to be too sophisticated.

MLH: We ran the Circus the other night, and it’s so simple. I’m the least pretentious director you’re going to meet.

While Michael said that last line straight, it was met with laughter around the room.

Let’s just watch on a loop Linda’s body language while she talks to Michael. (From the Get Back docuseries)

This is a real argument between two artists, a photographer and a film director, with legitimate differing visions. And no one held a higher status. Linda was just 27 (older than Paul and Ringo). Michael was 28. Each had about the same amount of professional experience at their respective trades, only a couple of years.

Paul returned after a phone call that couldn’t have lasted more than two minutes. Seeing his return, as shown in Get Back, is one of the great revealing moments in the documentary and something you never could have heard in a lifetime studying the Nagra tapes.

To this point, Paul spent the morning still in his overcoat. At any point, everyone could have called it a day and cut their losses. George wasn’t coming back. But when Paul dramatically — and joyously — removed his coat, revealing his magnificent black shirt, it was clear John wasn’t a issue.

“He’s coming in,” Paul said simply.

It’s a big deal, and the visual — of which we are now aware — really brings it to the forefront (if you’re looking for it). The Nagra tapes tell a lot, but audio alone can’t tell everything.

Through Paul’s return, Michael remained bold.

“You see, Paul, I was telling Linda when you were out, I could do it any way. Except I got to keep saying you’re wrong when I think you’re wrong.”

“Yeah, sure, great,” Paul replied, beaming and about to light a celebratory cigarette. “I’ll just keep saying I’m right when I think I’m right.

The daily circular discussion returned — again — to a pitch for Africa by Michael, one that was more quickly dismissed by Paul and Ringo than it had been, with the unspoken allegation of a trip being used as a crutch and gimmick.

Paul shared another idea he said he conceived the day before. That may have been a Sunday, but Paul’s brain had no days off.

“There’s another idea for a set: Instruments. You need a grand piano for one number, then for ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ … we should get a bit of a honky-tonk [piano]. So then you start to get the whole place just littered with instruments we could move around from. And it’s like a big game of musical chairs. Moving around on that amp, on that guitar, and it’s really planned. A whole computed setup … and then Ringo gets off and goes onto his congas for that one. That kind of sort of thing, then you get scenery, almost.

“You’re thinking of linking numbers,” Michael replied.

There were more shows used as points of reference — these guys absorbed so much TV:

The Potter’s Wheel: “They made a pot before your very eyes,” Paul explained. “Just one shot held, and it took about five minutes or something. And it was great, because you never felt bored. [I] always [watched it].”

Allow yourself the luxury of imagining a tween Paul McCartney soaking up these brief BBC interludes to the point of reminiscing about them at a moment he’s crafting on his own creative work at the height of his powers.

If the process should be the focal point, as Paul argued, it’s not enough for the instruments to create the scenery. Presaging the production of Get Back in 2021, he suggested the crew act as the supporting cast.

“Like [Glyn] switching everything over, you know, to taking all the top out of that on this track, ‘cause we want want a very biting guitar sound on this track.”

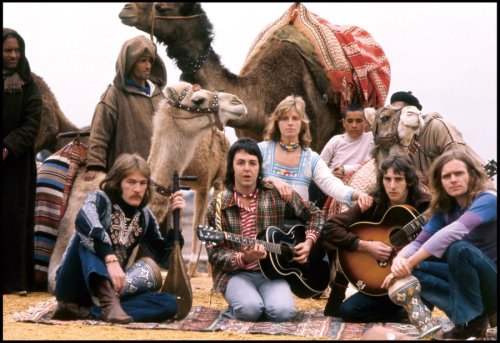

“I think that’s the documentary,” Michael argued, “because I think to go away to Glyn as opposed to a camel is distracting from you, because I think we’re getting into you. I think the documentary, we got all this in the documentary.”

Paul “totally” disagreed. “I think he’s a lot more to do with this show than a camel.”

After Neil jumped in to say Glyn was really a performer, too, Paul continued.

“That’s it! You’re going to miss him live. There he is. The camel won’t be doing anything live. Chances are it won’t even be looking at us or anyone. It won’t be looking at your camera, it will just sort of shit in front of you. Be lucky if it does, would be a bit of action.”

Camels with Wings. “Chances are it won’t even be looking at us or anyone.” (Photo from Paul’s Twitter).

Michael was truly exasperated, interrupting Paul who had continued his pitch, off the camel but back onto the fluidity of camera movements.

“See what I wanted to do in the desert,” Michael said, “was really make to the most dramatic thing of all time.”

Michael deserves credit for a lot of things having to do with his work in January 1969, including his real desire to create something exceptional and his willingness to exchange ideas. Here, he turned his attention back to the Beatles’ past, asking what was the band’s most successful and enjoyable TV appearance. Paul said “Around the Beatles,” an answer met with consensus from the others but unfortunately there was never any follow-up questioning to ask exactly why.

Still, it was yet another inspiration. Just like …

Some country music TV show Paul and Ringo “saw at the ranch”: Sparked off a comment from do-everything assistant Mal Evans, Paul and Ringo recalled a country music show. The “ranch” is certainly Reed Pigman’s in Alton, Mo., where the Beatles stayed Sept. 19, 1964. That would likely make Slim Wilson’s local country music show the memory. It was on at 6 p.m., right before “Flipper” — which the rancher’s son explicitly remembered watching with Ringo.

Some country music TV show Paul and Ringo “saw at the ranch”: Sparked off a comment from do-everything assistant Mal Evans, Paul and Ringo recalled a country music show. The “ranch” is certainly Reed Pigman’s in Alton, Mo., where the Beatles stayed Sept. 19, 1964. That would likely make Slim Wilson’s local country music show the memory. It was on at 6 p.m., right before “Flipper” — which the rancher’s son explicitly remembered watching with Ringo.

“There’s just one camera, and they all walked into it.” Paul recalled, describing Wilson’s show.

Ringo continued: “If it was the guitarist’s bit, he’d just step in and do it there. They’d all take the center, and if it was violin, he’d just walk in and do his bit, and he’d get back wherever he was. They acted all the movement.”

One memory sparked another, as often happens.

Unrealized Apple promotional film: “We were thinking of doing this once for an Apple thing, getting James Taylor, Mary Hopkin,” Paul remembered.

“We were going to get our home video things and set them up. And then have an area of the room which was lit, and that was it.. And then you came in, you did your thing and then if you wanted to say anything in close-up, you’ve walked up to the camera and you said it in close-up. Then you ducked out and someone else came in, in close-up and then walked into long shot and then did his dance.”

“So we can do a switch on this,” Paul said. “Get us to do the movement. Get us to go to the camera,”

Michael sought to punch holes in the idea, saying that if you were playing piano, movement was limited.

When Paul accused Michael of just being negative, Glyn said that was a “slight” contradiction.

“We’re all contradicting ourselves,” Michael said. “It’s the only way we ever get an idea.”

It was at this point Paul estimated John would arrive in about an hour, and with that news, the stage emptied out as everyone headed to lunch.

***

As an artist, Picasso announced when his film was complete — there was no haggling in a search for a conclusion. Sure, Picasso and Clouzot probably planned things out a little better before filming. It’s arguable the fluid state of the Beatles’ finale concert was expected to be an unspoken initial plot point of the Let It Be film, but if so, it was never pursued in the original film, only exploited later in Get Back. Maybe there’s something important to the relative age and experience of Picasso and Clouzot compared to the Beatles and Michael, too, in how it all played out.

The revealing debate between Linda and Michael justifiably reached the small screen in Get Back, but so much of the rest of this lengthy sequence remains left to the beautiful losers who labor to listen to the Nagra tapes in full. None of the revealing TV and movie comparisons above were featured in Get Back the docuseries or the book published in 2021.

Before the Let It Be film even came out, though, that sequence owned prime real estate. The very first page of dialogue in the original Get Back book — the one originally packaged with the Let It Be LP — spans this discussion. While the transcription is sloppy and incomplete, it’s there to set the tone for the text portion of the book, despite being from Day 8.

It’s absolutely no surprise the Beatles found inspiration in literally anything they encountered in film or television, whether it was something incredibly proximate, like the Rock and Roll Circus, or a pottery interlude they watched as kids or a rural country music show they caught just once. That’s how they synthesized their musical influences too. How George — absent for the discussion on the 13th — developed “I Me Mine” from watching a waltz on TV is a perfect example of all of this.

Michael Lindsay-Hogg filmed a lot a footage in 1969, and most of us didn’t really know what that meant from 1970 through late 2021. Let It Be, from 1970, was nothing like Get Back in 2021, the latter deliberately not following the former’s model. But did conversations like those on January 13, 1969, inform some of Michael’s decisions of how to build his documentary?

“Get right into one of John’s eyes,” Paul suggested. And sure, we get a few seconds here and there of extreme close-ups in Michael’s Let It Be, but these are hardly studies. That’s where the luxury of an eight-hour palette benefitted films like Warhol’s 1965 Empire — and Get Back in 2021.

Michael was clear that a “wide shot … with no particular response from the audience” was the wrong route. The success of the “Hey Jude” promo — with the band surrounded by the audience — was rooted in this strategy. It may have been the unspoken reason behind the affinity for Around the Beatles, too. And perhaps it’s why the rooftop performance in Let It Be was punctuated and interrupted consistently by street-level interviews. Otherwise, the Beatles were just playing on a very tall stage (which would have worked for me, but I’m not a filmmaker).

Still, the rooftop on January 13, 1969, was simply the top level of 3 Savile Row, not The Rooftop. Inspirations, open minds and contradictions were how they got to an idea.