The Beatles wanted to make a Lord of the Rings movie, going back more than 50 years. A half century later, they’ve got director Peter Jackson aboard, but for an entirely different film. Will this end up a fantasy, too?

Having maintained a monthlong silence on the 50th anniversary of the Get Back/Let It Be sessions, the Beatles raised the Dead Men of Dunharrow (that’s the Army of the Dead if you only saw the film) on the anniversary of the rooftop concert.

Quick takeaways here:

• The selection of Jackson was no accident. He obviously has a masterful storytelling ability while working within the constraints of very detailed and very iconic source material, as well as film restoration. While I don’t anticipate him to introduce Tauriel to, say, sit in on saxophone, I’m expecting something we’re not expecting.

Jackson’s a superfan, too, which can only be a good thing.

• I don’t believe having an “upbeat” Let It Be film is necessarily revisionist history — or fantasy, for that matter. I’ve long maintained there was plenty of sugar to along with the medicine when considering January 1969. It would be disingenuous not to include the tension, the arguing, the passive-aggressive relationships between the band members, and I think Jackson’s quote saying there was “none of the discord this project has long been associated with” is an overstatement. To whitewash that aspect of the sessions would be problematic (though not surprising, given the promotional work recasting of the White Album sessions 50 years later). But it would be likewise false to resissue the film as merely their “winter of discontent,” not that we should expect that.

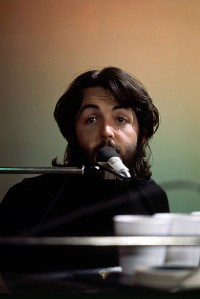

• Make no mistake: Let It Be is Michael Lindsay-Hogg‘s film. He wasn’t just behind the scenes, he was an active participant in the sessions. Listen to the tapes (or leave it to me and read this fine blog instead), and you can hear MLH’s voice more than anyone else who’s not in the band. I’m very curious to see how Jackson works with MLH’s ubiquity — he’s central to every discussion about the live show, and perhaps he’ll retroactively get his first acting credit, that’s how much screen time he could get, in theory.

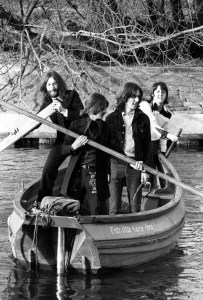

• And about that live show. I’ve written it before, but clearly the film’s arc should be (and have been) the sort of near-comedy of the greatest group in the world wondering what to do next and how — and that includes debating their own future — throwing out every idea they can think of, only to have someone argue against it. Finally, after ups and downs (George quitting), the villian (Twickenham Film Studios) is vanquished, a bit player from their past (Billy Preston) emerges out of nowhere to help return order, and everyone realizes the simplest solution (rooftop show) is what they were looking for all along. The farther one travels, the less one knows, so find the answer at home.

• I won’t call this a buried lede, but not even mentioned in the social media blitz — only the Beatles’ press release — is this news:

Following the release of this new film, a restored version of the original Let It Be movie directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg will also be made available.

Quite the “oh, by the way …”

This is, of course, good news. Let It Be is a critical document, too, despite it’s obvious flaws, and we haven’t seen an official release since it the days of LaserDisc and VHS.

• The 140 hours of audio cited by Jackson is quite a bit more — in excess of 50 hours or so — than we’ve already have heard leaked and bootlegged over the years. It could be 24 more hours of discussions about a live show (I’m hoping) or 24 more hours of Maxwell’s Silver Hammer outtakes (I’m expecting). Reality, as usual, will likely be somewhere in between. I can’t see anything that changes the direction of history, but maybe we do get a few more specifics on locations. And I’m sure we get some improvisations or clipped covers we never heard.

• I’ll admit I was wrong about something — but I’ll bury it at the bottom of this post. I never thought the Beatles would release Let It Be while Paul, Ringo and Yoko were still with us. And I thought, once Paul announced several months ago that some new version of the film was to be released, we’d probably just get Let It Be content lumped in as part of an Abbey Road deluxe set — “Beatles ’69.” But I was wrong there, too. Mea culpa.

• That said, we didn’t hear a thing about getting some of the audio outtakes — Nagra or otherwise — finally released. I’m still not expecting any sort of sweeping set — do you really think they’re going to put out tapes of Paul calling a newspaper “cunts” or, more relevantly, acknowledging how negative they are and doubting their future? — but maybe we will get a disc or two of some January 1969 upbeat highlights — “Suzy Parker,” “Oh Julie, Julia,” “Commonwealth,” etc. And there’s certainly enough terrific material to fill several Abbey Road “demo” discs, too.

The most disappointing part of the announcement is the timeline: It hasn’t been announced yet. But simply to get news of a new (and old) Let It Be is reason enough to celebrate with an unexpected party.